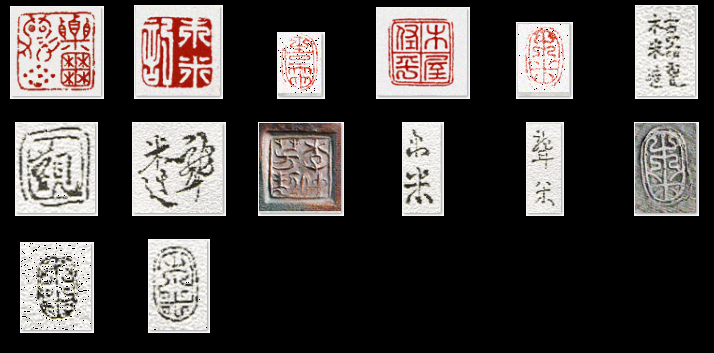

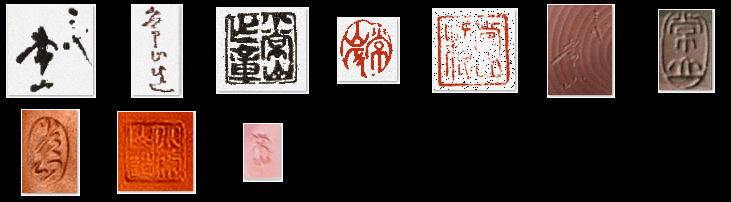

Famous Japanese potters and marks

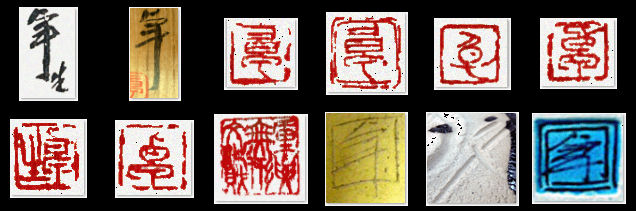

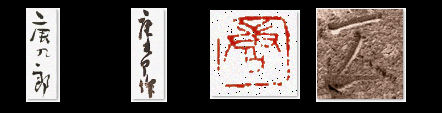

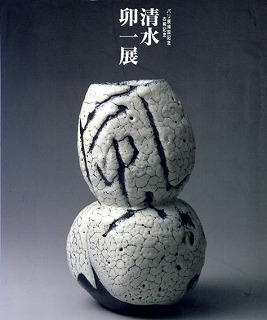

Aoki Mokube / *Arakawa Toyozo / Bernard Leach / Eiraku Zengoro / *Fujimoto Yoshimichi / *Fujiwara Kei / *Fujiwara Yu / Hamada Shinsaku / *Hamada Shoji / *Hara Kiyoshi / Hirasawa Kuro / *Imaizumi Imaemon XIII / *Inoue Manji / *Isezaki Jun / *Ishiguro Munemaro / Itaya Hazan / *Ito Sekisui V / *Kaneshige Toyo / Kato Bakutai / *Kato Hajime / Kato Sekishun / Kato Shuntai / *Kato Kozo / *Kato Takuo / Kato Tokuro / Kato Usuke / Kawai Kanjiro / Kawai Takekazu / Kawakita Handeishi / *Kinjo Jiro / Kitaoji Rosanjin / Kiyomizu Rokubei / Koie Ryoji / *Kondo Yuzo / Koyama Fujio / Kuroda Koryo / *Maeda Akihiro / *Matsui Kosei / *Miura Koheiji / *Miwa Kyusetsu X / *Miwa Kyusetsu XI / Murata Gen / Nakagawa Jinenbo / *Nakajima Hiroshi / Nakamura Donen / *Nakazato Muan / Nishioka Koju / Nonomura Ninsei / Ogata Kenzan / Ogawa Choraku / Ohi Chozaemon / Okuda Eisen / Otagaki Rengetsu / Raku Kichizaemon / Ri Masako (Yi Bangja) / Saka Koraizaemon / Sakaida Kakiemon XIV / Sakakura Shinbei / Sasaki Shoraku / Seifu Yohei / *Shimaoka Tatsuzo / *Shimizu Uichi / Suda Shoho / *Suzuki Osamu / Takahashi Dohachi / *Tamura Koichi / *Tokuda Yasokichi / Tokuzawa Moritoshi / *Tomimoto Kenkichi / *Tsukamoto Kaiji / Tsukigata Nahiko / *Yamada Jozan III / *Yamamoto Toshu / *Yoshida Minori

*an individual holder of Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure)

Aoki Mokube (1767-1833 )

Aoki Mokubei was born in the Gion district of Kyoto as Aoki Sahei.

From childhood, he was a disciple of the well known artist and Confucianist Kou Fuyou, who had a strong influence on his upbringing.

When he visited Kimura Kenkadou of Osaka, he found among his book collection a book written by the Chinese Shuryuutei called “Guide to Ceramics”, which, it is said, inspired him to decide that ceramic art was his life’s calling.

It is said that his mentors in ceramic art were Okuda Eisen, who taught him how to work porcelain, and Houzan Bunzou the 11th, who taught him how to work pottery, although it is also said that most of his knowledge was gained through self study.

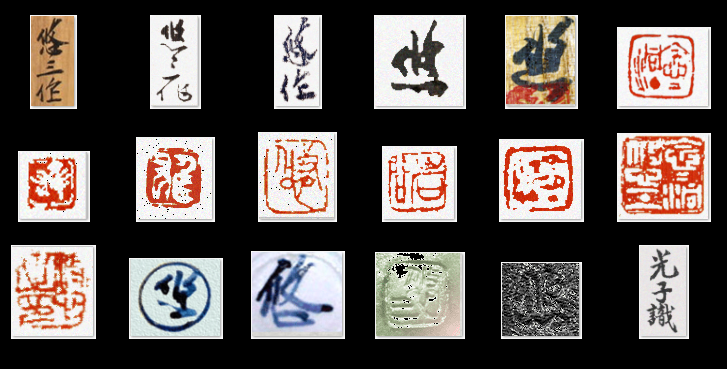

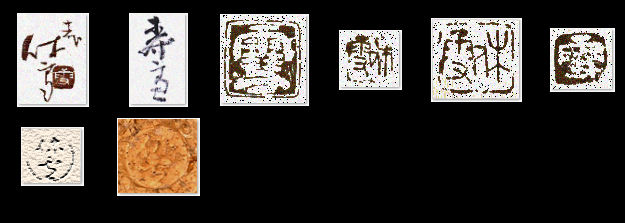

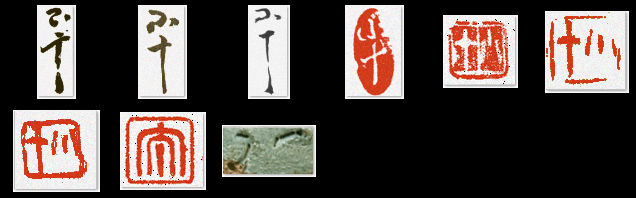

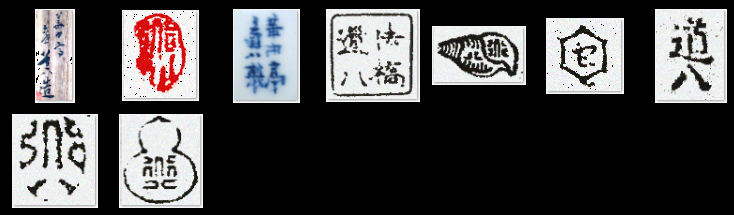

He set up shop in the Awata region of Kyoto. He took the name of the tea house run by his family, “Ki” (木), combined the characters of his nickname “Yasohachi” (八十八) into one character, “Kome” (米), and added them together to create the name “Mokubei” (木米), and worked under that name. With his natural genius, he became one of the most famous potters in Kyoto-Osaka after just a few years. In 1801, Tokugawa Harutomi of the Wakayama area heard of his fame and invited him to participate in the construction of the Zuishi kiln. It is said that this is when he was bestowed with the Silver Seal of Teiunrou, but there are differing opinions and no concrete evidence.

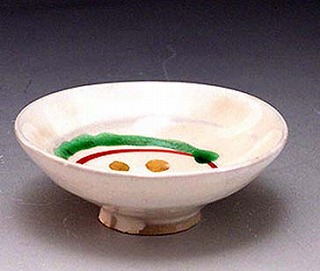

In 1805, he was ordered to serve at Awata Palace. The next year, he went to Kanazawa, in Kaga Domain, and began working at Mount Utatsu. He briefly returned to Kyoto before going back to Kanazawa in 1807, where he established the Kasuga-yama kiln. After abandoning it to return to Kyoto, he stayed in Kyoto permanently and continued his pottery there. In addition to the Chinese and Choson styles, he researched many different styles of ceramic art such as European, Cochin ware, blue and white pottery, akae (enamel decoration on porcelain), Dehua pottery, and Mishima ware. He created a lot of tea utensils, focusing mainly on kettles, and those creations became the foundation for modern Japanese tea utensils, referred to today as "Mokubei style". In addition to pottery, he excelled in painting and Han Studies, had a sophisticated demeanor, and made close friends with many intellectuals such as Tanomura Rakuden and Rai San'yo.

His representative work, “Bokutansai Sansui-zu” and other works have been classified as Important Cultural Properties of Japan.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 55,000,000 JPY.

Arakawa Toyozo (1894-1985)

Around 1586, Shino ware suddenly appeared in records of tea ceremonies, being used as the bowl The Shino ware was being used as the tea bowl in tea ceremonies. During the Keicho period, problems with production efficiency and other issues caused a decline and eventually a complete halt in production.

Arakawa Toyozo, after experiencing much difficulty, revived the tradition of Shino ware, which became a success. He was eventually named a Living National Treasure and is regarded as one of the finest potters in history.

Born on March 21st, 1894. Educated by Miyanaga Tozan, went to Kamakura and aided in the making of pottery at Kitaoji Ronsanjin. In 1930, he discovered the process of using a kiln from the Momoyama period at Ogaya in the Kani district of Gifu prefecture. Nearby, he began to work, building a kiln and reproducing Shino, Yellow Seto (Kizeto), and Black Seto ware (Setoguro). 30 years as a Living National Treasure and 46 years in the Order of Culture. Died August 11th, 1985 at 91 years of age.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 30,000,000 JPY.

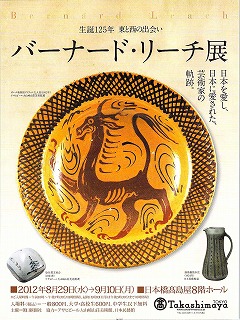

Bernard Leach (1887-1979)

After losing his mother as a baby, Leach spent his early childhood in Kyoto raised by his father, a Japanese resident.

He later returned to England, but came back to Japan in 1909 aged 21. Connecting with writers and artists from the Shirakaba Group, he was especially friendly with Yanagi Soetsu, and became captivated by ceramics. He began studying ceramics under Ogata Kenzan the 6th, producing Raku ware and so on.

He endeavored in pottery techniques at Hamada Shoji's Mashiko kiln base, became acquainted with Kawai Kanjiro and participated with him in Yanagi's mingei movement. In 1920 he returned to England accompanied by Hamada, and established a Japanese style Noborigama kiln in St Ives, known as the Leach Pottery.

Afterwards he went to and from Japan and England, working on pieces and developing unique works that fused Eastern and Western cultures.

Leach was awarded an Order of the Sacred Treasure 2nd Class in 1966 and a Japan Foundation Prize in 1974. He passed away in 1979 aged 92.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Nishimura Ryozen (Eiraku Zengoro X) (1771-1841)

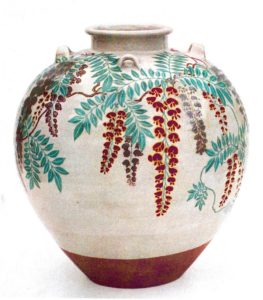

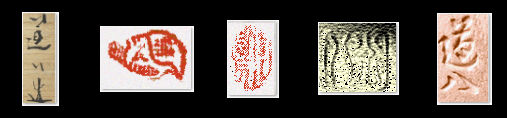

Born to the Ninth Generation Sogan, he lost both parents at a young age, then lost his home in the Great Tenmei Fire. Was able to restore his household in Ichijobashi with assistance from the Sanzen family among others. In addition to his trade of manufacturing Doburo tea kettles, he also had experience working with Seto, Annam, and Kouchi ware. In 1817 (14th year of the Bunka era), he adopted the name of Ryozen, with the character "Ryo" being taken from Ryoryosai Sosa of the Omote Senke school. Because the generational records, as well as the Sozen Seal that served as the symbol for each generation were lost in the Great Tenmei Fire, details and records pertaining to Ryozen's predecessors are less clear. In the generations following Ryozen, the seals used were original, and became increasingly varied.

Nishimura Hozen (Eiraku Zengoro XI) (1795-1854)

At first, he was a "kasshiki", an attendant charged with announcing mealtimes to the monks, working under Daiko Sogen at Daitoku-ji Temple. However, with Daiko Sogen's help, he became an adopted child of Ryozen when he was around 12 or 13 years of age. After that, he researched the making of pottery, and in 1817 (14th year of the Bunka Era), he succeeded to the name of Zengoro. Then, in 1827 (10th year of the Bunsei Era), he, along with his father Ryozen as well as others such as Kyukosai Sosa and Raku Tannyu, were called upon by Lord Kishu-Tokugawa and engaged in Kishu Oniwayaki pottery. He was bestowed the signatures of "Eiraku" and "Kahin Shiryu" by Lord Harutomi, and since then he began to use "Eiraku" for his signatures, etc. In 1843 (14th year of the Tenpo Era), he left his business to his son Sentaro (who will later become Wazen) and took on the name Zennichiro. However, he left behind many remarkable works created even after this point in time. In 1846 (third year of the Koka Era), he was granted the name and signature of "Tokinken" by Prince Takatsukasa. In his later years, he took on the name of Hozen and proceeded to Edo. After that, he did not return to Kyoto and founded Konanyaki pottery at Omi. At one point, he was summoned by Lord Nagai of Takatsuki and was active in various regions in Takatsuki, making pottery such as blue and white sometsuke pottery. In terms of style, he mainly produced items used for tea and daily necessities, using styles such as the gold brocade kinrande style, blue and white sometsuke pottery, the Annan style, Cochi pottery and the Shonzui style.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Eiraku Wazen (Eiraku Zengoro XII) (1823-1896)

Eldest son of Hozen. He was very fond of Ninsei, and in 1852, he and his younger brother-in-law, Munesaburo (Kaizen) opened the new Eiraku Omuro Kiln on the remains of the Ninsei Kiln. Afterwards in the 14th year of the Tenpo Era (1843), he inherited the 12th generation name of Eiraku due to his father Hozen's retirement.

After that, in the second year of the Keio Era (1866), he was invited by Maeda Toshinaka of the domain of Daishoji in Kaga, and he opened the Kutani Eiraku Kiln with Munesaburo and his son Tsunejiro (who would later become Tokuzen) in order to improve Kutani pottery. He engaged in this for six years. He also experienced suffering and such due to the debts left behind by Hozen, but he greatly endeavored even after this time.

After returning to Kyoto, he changed his surname in 1872 (fourth year of the Meiji Era) to Eiraku (up until that point, his surname had been Nishimura and Eiraku was an alias) and two years later, he was invited to Okazaki in Aichi Prefecture and opened a kiln there. He created a wide range of pottery, mainly of the gold brocade kinrande style, the Nanking style, gosuakae red pottery and others and Western tableware etc.

In his later years, he moved near Kodai-ji temple in eastern Kyoto and opened the Kikutani Kiln. It was from this point onward that he started to become hard of hearing, and he began to call himself "Jiroken" which is a name that includes the words, "deaf ears."

His style has a wide breadth, including the Ninsei style, the gold brocade kinrande style, akae red pottery, Cochi and celadon. He also created his own techniques, such as using gold leaf in the gold brocade kinrande style, compared to Hozen, who instead used gold paint. He died on May 7th, at 74 years of age.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 60,000,000 JPY.

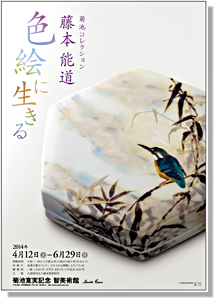

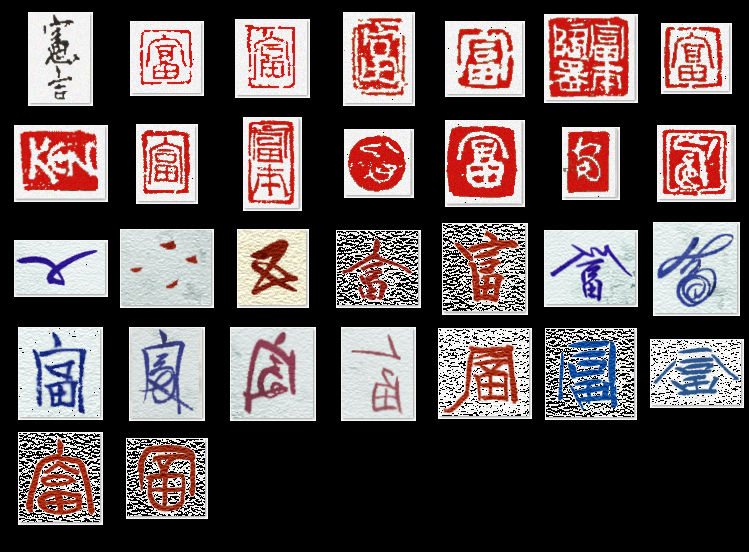

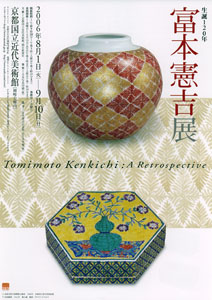

Fujimoto Yoshimichi (1919-1992)

After graduating from art school ad being admitted to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology’s industrial arts engineering training center, Fujimoto entered into an apprenticeship under Kato Hajime, and began producing works alongside Tomimoto Kenkichi as his pottery assistant in 1938.

Fujimoto won the Kofukaiten Kofukai Kogeisho Award in 1938, and after World War II exhibited works primarily in the various exhibitions held by the Japan Ceramics Society. Fujimoto won an award from the society as well as the silver prize from the International Academy of Ceramics in Geneva in 1956.

Furthermore, though Fujimoto for a time was a member of the avant-garde Sodeisha Society where he produced odjet d’art ceramics in addition to other kinds of pottery, from the mid 1960s he returned to more traditional styles, immersing himself in research of painted porcelain.

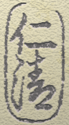

Developing works that feature the motifs of flowers and birds, painted with such realism that’s evocative power superseded that of Nihonga artists. In addition to this, he created unique techniques such as that of Yubyokasai wherein images are added to works before firing via colored glazes, and it was for these techniques that he was designated as a holder of the title Nationally Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) in 1986.

In the interim however, after assuming a position as an instructor at the Kyoto City University of Arts in 1956, he continued to dedicate himself to his own education and guidance of a new generation of artists at the school in Kyoto as well as at Tokyo University of the Arts until 1990 (ending his tenure as dean of Tokyo University of the Arts), while also winning awards such as the gold prize from the Japan Ceramics Society and a Medal of Honor from the Government of Japan with a dark blue ribbon in the same year. For his seal, he is fond of suing the Kuma or bear seal made by Kenkichi.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 30,000,000 JPY.

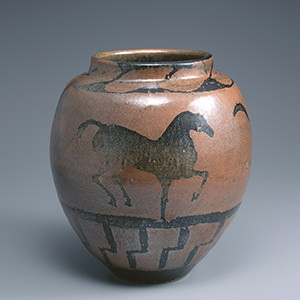

Fujiwara Kei (1899-1983)

Starting out with a passion for literatary studies, Fujiwara began submitting haiku and poems throughout his elementary and junior high school years to various publications and winning awards for some of his submissions. Leaving for Tokyo at the age of 19, he began working as an editor for Hakubunkan while also attending university and was producing poems under the pen name Fujiwara Keiji. However, due to poor health, he abandoned his aspirations of becoming a writer of literature and returned to his hometown in 1973.

After returning home, Fujiwara began to practice pottery at the suggestion of Manyoshu scholar Masamune Atsuo, going on to become the apprentice of Bizen potter Mimura Umekage.

Getting his first kiln in 1939, Fujiwara then started out on his own, and thanks to the guidance of Kanashige Toyo as well as deepening his understanding of the unique ko-bizen style of pottery, he developed works in the solemn style of Momoyama and Kamamura period ceramics. After the war he was recognized as a conservator of bizen ware techniques in 1948, was designated an Important Intangible Cultural Property by Okayama Prefecture in 1954, became a regular member of the Japan Kogei Association in 1956, and in 1970 became the second person to be designated a Living National Treasure for bizen ware pottery after Kanashige Toyo.

In addition to this, he was awarded the Order of the Rising Sun 4th Class in 1972, received the Miki Memorial Award from Okayama Prefecture in 1973, and was also awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure 3rd Class on the day of his death in 1983.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

Fujiwara Yu (1932-2001)

Born as the eldest son of Living National Treasure for bizen ware Fujiwara Kei, after graduating from university, Fujiwara worked for a time as a magazine editor, but was convinced by his father and Oyama Fujio to return home where he began his tutelage in ceramics under his father.

After this, Fujiwara went on to produce work after work, presenting them in exhibitions by the Nihon Kogeikai, the Gendai Nihon Togei, and the Issuikai, eventually becoming a member of the latter in 1960, and becoming a regular member of the Nihon Kogei Association the following year.

Fujiwara won the grand prix prize in the Barcelona International Pottery Exhibit, which then gained him attention in the United States, Canada, Spain and various other countries in 1964 when he was asked to instruct in pottery around the world as a visiting lecturer.

Fujiwara opened his own workshop in Honami, Bizen in 1967, and after starting to work independently, won the Nihon Toji Kyokaisho award, thereupon going on to win the Kanashige Toyo award in 1973 and being recognised as an Important Intangible Cultural Property by Okayama Prefecture in 1978. In 1984, he won the Sanyo Shimbunsha Award, was awarded the Medal of Honor with a dark blue ribbon by the Japanese Government and won the Okayama-ken Bunkasho Award both in 1985, the Chugoku Bunkasho Award in 1986, the Okanichi Geijutsu Bunka Korosho Award in 1987, and the Geijutsu Sensho Monbu Taijinsho Award in 1990. With such a prestigious history of awards behind him, Fujiwara became the 4th person to be designated a Living National Treasure for bizen ware in 1996 after Toyo, Kei, and Yamamoto Toshu, and was also awarded the Medal of Honor with purple ribbon by the Government of Japan in 1998.

Striving to create ceramics that placed an importance of usability that would be suitable as both tea bowls and for dining while also working to bring out the uniquely quiet and subdued simplicity of the works of bizen ware to the utmost, Fujiwara’s works serve as the basis of modern bizen wares that place an emphasis on both usability and beauty.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

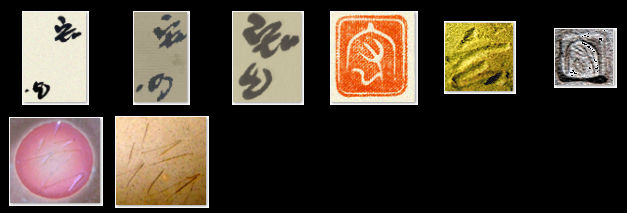

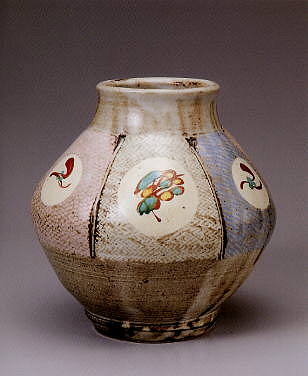

Hamada Shinsaku (1929- )

Born as the second son of Living National Treasure Hamada Shoji, Shinsaku moved with his family to Mashiko, Tochigi Prefecture when he was only several months old. It was here that he developed an interest in pottery, and it was in junior high school that he committed himself to carrying on his father’s legacy by becoming a pottery.

Around 1950, at the same time as when he graduated from university, Hamada began his own training in pottery in his father’s workshop. In 1963, he served as an assistant to his father and Bernard Leach as they toured America giving lectures in ceramics. After this, he exhibited his own pieces in his father’s private exhibitions as well as in Kokugakai exhibitions. He became a member of the Kokugakai in 1978, and though he did produce work while a member, he eventually resigned from the organization in 1992 and now puts on his own private exhibitions in department stores and galleries in various locations as an independent artist. In addition to this, he was awarded the grand prize at the Salon de Paris in 1987, and is now a member of the society.

Taking on the simpler aspects of folk ceramics such as using iron, ash, persimmon, and salt glaze, he also serves as an official expert on his father Hamada Shoji and Bernard Leach’s works.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 1,000,000 JPY.

Hamada Shoji (1894-1978)

Hamada Shoji was a renowned craftsman and representative figure in modern Japanese pottery. Born in Tokyo in 1894, he resolved to become a potter while still a student at Furitsuicchu (the Tokyo First Prefectural Jr. High School, Hibiya high school at present). After studying ceramics at the Tokyo Higher Technical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), Hamada joined the Kyoto Municipal Ceramic Laboratory, where he would meet his lifelong friend, Kawai Kanjiro. As Hamada later summarized the narrative arc of his career, “I found the path in Kyoto, began my journey in England, studied in Okinawa, and developed in Mashiko.” In 1920, he accompanied Bernard Leach to England where he began his practice as a potter. When the time came to return home to Japan, he sought a quiet life in the countryside, and situated himself in the town of Mashiko in 1924. During this period, he also made an extended sojourn in Okinawa, which became the inspiration for a large number of works. In 1930, he relocated the building which would later become the main residence of his compound (later donated to the Ceramic Art Messe Mashiko), and in the years up until 1942, transplanted many traditional old houses onto the premises to create a workshop and residence. It was from this base that he founded the Mingei folk-art movement along with cohorts Yanagi Soetsu and Kawai Kanjiro, which was to have a significant impact on the Japanese craft world. In 1955, Hamada was recognized along with Tomimoto Kenkichi et. Al. as an inaugural recipient of the Japanese government’s “Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties” (Living National Treasure) designation, and in 1968, became the third potter to be awarded the prestigious Order of Culture.

The Mingei Movement

The Mingei (folk-art) movement was initiated by Yanagi Soetsu, Kawai Kanjiro, and Hamada Shoji in 1926 (Taisho 15) as an approbation of functional craftwork used by the masses in the course of daily life. At the time, the craft world was dominated by decorative pieces prized for their aesthetic value. In response, Yanagi and cohorts promoted the quotidian lifestyle implements handmade by anonymous craftsmen as mingei (“craft of the common folk”), arguing that such works have a beauty that rivals fine art, for beauty can be found in the everyday. A further pillar of the movement introduced a “new way of looking at beauty” and “aesthetic values” via the notion that crafts born from the local practices and rooted in the rhythms of the rural regions of Japan embody a utilitarian, “healthy beauty.” Their ideology was, in many ways, related to the era, marked as it was by the advance of industrialization and tandem gradual influx of mass produced products into the sanctum of daily life. Troubled by the loss of “handicraft” across Japan, the Mingei movement warned against the easy progression of modernization/Westernization. In this way, the Mingei movement served as a vehicle for the artists to pursue the question of what constituted a good life, rather than simply a life rich in material wealth.

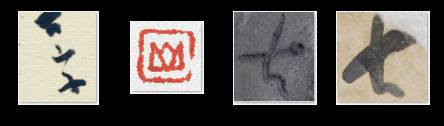

Mongama

A kiln of Mashiko-ware pottery headed by Hamada Shoji. Since establishing the kiln in 1931, Hamada and his disciples have presented many works in succession using Mashiko traditions and materials. Mashiko's recent rise to prosperity as a major production area for folk-craft ceramics has been greatly influenced by the ceramic-making activities of this site. Hamada's achievements were recognized in 1955, when he was designated as the first individual holder of Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure). Following his death, Hamada's son Shinsaku took over the kiln and has been teaching highly reputed potters.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

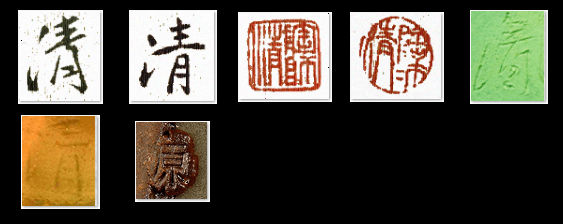

Hara Kiyoshi (1936–)

An aspiring potter, Hara Kiyoshi became an apprentice of Ishiguro Munemaro in 1954, later studying under Munemaro's top disciple Shimizu Uichi.

He opened his own kiln in Setagaya, Tokyo in 1965, after previously participating in the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition for the first time in 1958 and becoing a regular member of the Japan Kogei Association in 1961.

After opening his own kiln, he was conferred the Chairman's Award at the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 1969, the Japan Ceramic Society Award in 1976, and the Tokyo Governor's Award at the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 1997.

He was also very active arranging solo exhibitions at Mitsukoshi Nihonbashi and elsewhere as well as producing a broad range of works for exhibitions at home and abroad that he was invited to.

From the beginning, Kiyoshi experimented with iron glazes, underglazing plants, birds, and animals in iron on dark-brown glaze to create elegant and strikingly unique works. From the 1980s, he began making blue-glazed pieces characterized by their lucid blue color. He was a special invitee to the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 2001 and was recognized as a Holder of National Important Intangible Cultural Heritage (Living National Treasure) in 2005 for his glazed porcelain.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Hirasawa Kuro (1772-1840)

Samurai and ceramic artist during the late Edo Era.

Born in 1772, he was a member of the Owari Nagoya Clan. Hirasawa enjoyed the tea ceremony, and made teaware in the koseto and karatsu styles in his free time. His creations had a unique quality and were known as Kuroyaki. He died at the age of 69 on June 23, 1840. His name was Kazusada. His alias was Seikuro. Also Konjyakuan.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 1,000,000 JPY.

Imaizumi Imaemon XIII (1926–2001)

The eldest son of Imaemon XII, Imaemon XIII studied at Arita Technical School and Tokyo Schhol of Fine Arts before returning to his hometown to study pottery under his father.

In 1975, his father passed away and he became the 13th Imaemon. (During this time, he participated in exhibitions such as the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition and the Issui Society Exhibition, was conferred the Issui Society Chairman's Award and the Japan Kogei Association Chairman's Award, as well as was nominated for member and regular member of both exhibitions.)

After his succession, Imaemon XIII arranged solo exhibitions in various locations to commemorate the occasion, and in 1976 he established the Ironabeshima Technique Preservation Society (Important Intangible Cultural Heritage) together with highly skilled potters in his studio.

Subsequently, he continued to preserve tradition while also incorporating new techniques in his constant quest for modernistic pottery. He participated in traditional arts exhibitions and other public exhibitions as well as contributed to the development of local society and the training of a new generation. Throughout the years, he was conferred numerous awards and commendations, such as the Japan Ceramic Society Award in 1976; the Saga Arts and Culture Award in 1979; the West Japan Culture Award in 1984; the Medal with Purple Ribbon, the Saga Award for Distinguished Service, and the Saga Newspaper Culture Award in 1986; as well as the Mainichi Arts Awards and the 1st MOA Okada Mokichi Grand Award in 1988. He was also recognized as a National Important Intangible Cultural Heritage (Living National Treasure) in 1989, received the Japan Ceramic Society Gold Award in that same year, and was conferred the Order of the Rising Sun, 4th Class in 1999.

Imaemon XIII held solo exhibitions not only in Japan but also in Spain, Portugal, and Paris, where he was very well received. In 1995, he received the Commendation Award of the Japanese Foreign Minister for his contributions to international cultural exchange.

He inherited the traditional Ironabeshima technique, but from the beginning his aim was to achieve a modern style of pottery. Based on the "fukizumi" technique of spraying a gosu-blue glaze, he developed the "usuzumi" and "fukigasane" techniques, new to the Imaemon tradition. It is this expressiveness that has earned the modern Imaemon his high praise.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY.

Inoue Manji (1929- )

Born into an old potter family, he trained next door at the Kakiemon Workshop. After beginning an independent career, he earned awards, starting in 1958 at the Saga Prefectural Exhibit, the Seibu Crafts Exhibit, the Issuikai Exhibit, and the Japanese Traditional Crafts Exhibit. In 1987, he was awarded the Minister of Education, Science and Culture Award at the Japanese Traditional Crafts Exhibit.

In the meantime, he was appointed a professor at the Saga Prefectural Ceramics University and applied his energy to teaching young potters as well. In 1986, he received the Saga Prefecture Traditional Culture Distinguished Service Award, in 1990 he was recognized as a holder of Saga Prefecture's Important Intangible Cultural Property, and in 1995 he earned the honor of being a holder of National Important Intangible Cultural Property (National Treasure).

His style is based on white porcelain and displays exceptional craftsmanship with the warmth of flower-patterned engravings and blue glaze. He is highly esteemed as one of the standout porcelain potters.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Isezaki Jun (1936-)

Born the second son of famous craftsman, Isezaki Yōzan, Isezaki Jun learned pottery from his father at a young age alongside his older brother Misturu, and began making pottery in earnest after graduating from university.

In 1961, he was selected for a prize in the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition for the first time, and after continuing to be selected since then, was inaugurated as a full member of the Japan Art Crafts Association in 1966.

In 1967, he built a kiln and became an independent craftsman. In 1977, he traveled to the United States and broadened his horizons to making sculpted pottery as well, represented by his display of an ambitious stance towards contemporary objet d'art pottery, such as taking charge of the Bizen ware relief mural decorations in the main entrances of buildings including the Prime Minister's residence, Bizen City Office, Kurashiki Notre Dame Memorial Museum etc. While he was regarded highly since long before for his yohen firing techniques, such as the hidasuki pattern, in recent years he has developed pieces that are clearly different from existing Bizen ware, such as works of sculpted pottery that mixes the yohen firing effects unique to Bizen ware with black glaze. In 2004, he was appointed the fifth National Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) of Bizen ware.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

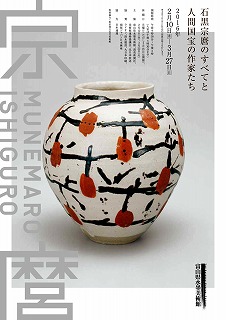

Ishiguro Munemaro (1893-1968)

Ishiguro Munemaro roamed areas such as Tokyo, Saitama, Toyama and Kanazawa as he created his pottery works, before building a kiln at Ohara, Kyoto and settling down in 1935. He then became close to individuals such as Koyama Fujio, Katō Hajime, Kaneshige Toyo, Arakawa Toyozō and Katō Tōkuro and founded the Tōri Society and the Kashiwa Society among others.

His style was of free-spirited expression, and he showed outstanding talent in fields such as black glaze, iron glaze, iron painting, temmoku glaze, Karatsu ware, overglaze enamel and ash glaze.

In particular, he was acknowledged as a holder of cultural property with his temmoku glaze in 1953. Then in 1955, he was acknowledged as an Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) with his iron glaze pottery works.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 30,000,000 JPY.

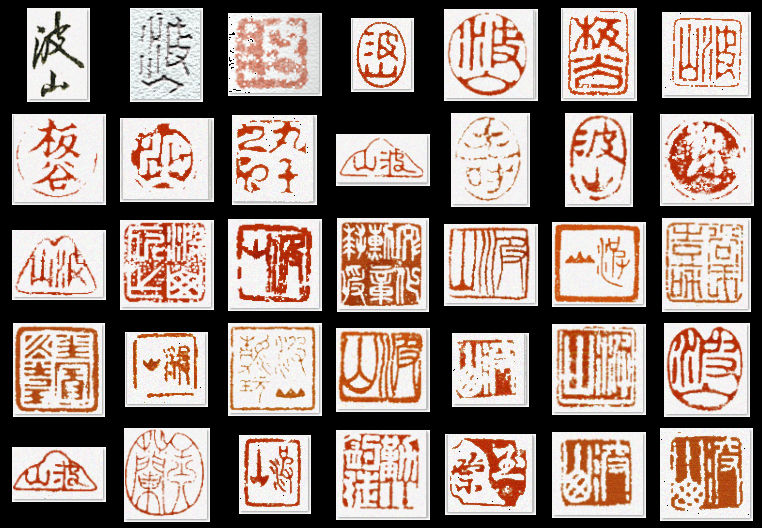

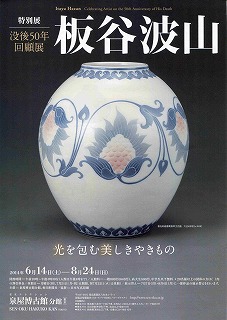

Itaya Hazan (1872-1963)

Graduated from Tokyo Art School (Tokyo University of the Arts) in the Sculpting Department.

Learned alongside students such as Okakura Tenshin and Takamura Kōun.

He built a home at Tabata which also doubled as a workshop, and after installing a downdraft style kiln, he devoted himself to creating pottery in order to utilize the fruits of the research on pottery he had engaged in up until that point.

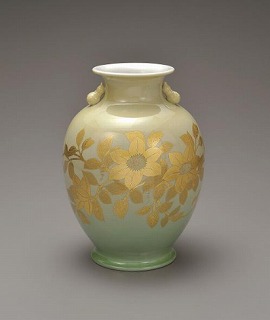

In 1907, he exhibited his work, "Jisei Kinshimon Kesshoyu Vase" at the Tokyo Industrial Exposition and won third place prize.

After winning many prizes, he was appointed an Imperial Household Artist in 1934. In 1945, his home and workshop was burned down in the Bombing of Tokyo. He temporarily evacuated to his hometown of Shimodate before rebuilding a workshop in Tabata again in 1950. In 1953, he became the first potter to receive the Order of Culture. In 1955, he declined the offer to be designated as a Living National Treasure.

As a potter who studied the foundations of art, he is a pioneer for establishing contemporary pottery art that is different from traditional pottery.

His representative works include, "Hokosaiji Chinkamon Vase" (property of Sen-oku Hakuko Kan Museum, Important Cultural Properties), "Saiji Enjumon Vase" (property of Idemitsu Museum of Arts), "Saiji Kinkamon Vase" (property of Tsurui Museum of Art), etc.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 100,000,000 JPY.

Ito Sekisui V (1941- )

Born into a family of traditional Mumyoi-yaki potters, while inheriting the method for making traditional Mumyoi-yaki pottery and creating pottery full of contemporary feeling , in 1980 he won awards at the Traditional Crafts New Work Exhibition and the Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition. In 1985 he won Japan Ceramics Exhibition's Best Work Award, and in 1987 he won the Japan Ceramic Association Award.

With his traditional technique incorporating unique color variations known as "Mumyoi youhen" and the kneading technique known as "Mumyoi kneading", the outward appearance displays the originality of Ito Sekisui V. Also, further spreading the potential of Mumyoi-yaki, in 2003 he was recognized as a nationally designated Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure).

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Kaneshige Toyo (1896–1967)

Born into the Kaneshige family, one of the six kilns of Bizen, as the son of wakigama-style potter Kaneshige Baiyo, Toyo was trained by his father from early childhood and became adept at pottery techniques, with handicrafts and engraved ornaments being his particular specialty. He further devoted himself to the study of kiln construction. In 1921, he built a German-style map kiln, allowing him to successfully fire kiln-effect pottery (yohen-mono). He went on to study pottery clay as well, successfully recreating the sheen of Momoyama-period Bizen pottery in 1930. In 1939, he also succeeded in firing scarlet-stroke (hidasuki) kiln-effect pottery. In this way, he devoted himself to the restoration of traditional Bizen pottery and became the founder of modern Bizen pottery.

Also in this period, he held his first solo exhibition in 1936; founded the "Karahine Society" together with Arakawa Toyozo, Miwa Kyuwa, and Kawakita Handeishi in 1942; was certified as an Authorized Preserver of a Craft also in 1942; was selected as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 1952; founded the Tori Society in Tori, Izusan, together with Ishiguro Munemaro, Kato Hajime, Arakawa Toyozo, and Kato Tokuro in 1954; and was certified as an Important Intangible Cultural Heritage (Living National Treasure) for his Bizen pottery in 1956.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 30,000,000 JPY.

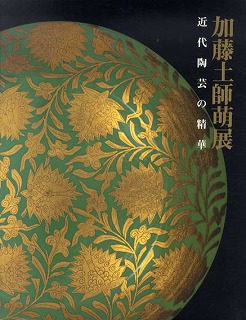

Kato Bakutai (1861-1943)

Bakutai, whose true given name was Yutaro, was a master potter active between the Meiji period and the prewar Showa period. He was a disciple of Kato Shuntai, who is said to be responsible for the resurgence of the Seto pottery style. He is also said to have influenced the potter Kato Tokuro.

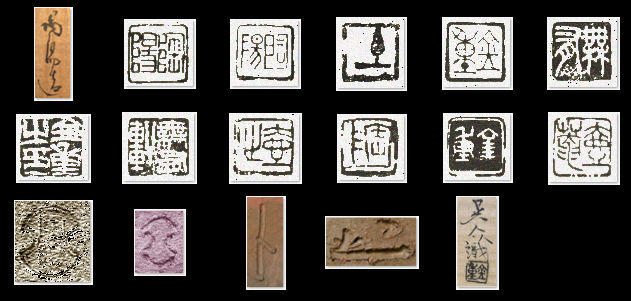

Kato Hajime (1900-1968)

First studied design etc., under pottery art designer Hino Atsushi, afterwards working at Gifu Prefectural Ceramics Research Institute and starting to create pottery on the side in 1926. In 1927, he was selected for a prize for the first time in the eighth Exhibition of the Imperial Fine Arts Academy in the fourth category, the Industrial Art Category, which was newly established in the same year. Since then, he continued to exhibit his works, and took on the name "Hajime" from 1930.

Additionally, he received the Grand Prize at the Paris International Exposition in 1937, and in 1940, he built a kiln in Yokohama and focused on researching the glaze of China's Ming Dynasty, creating a fusion of it with Seto glaze and receiving the Chunichi Cultural Award in 1952. In 1954, he established the 'Touri Society' in Touri, Izusan with Ishiguro Munemaro, Kaneshige Toyo, Arakawa Toyozo and Kato Tokuro. Furthermore, he left contributions in the research of porcelain as well, such as red-figure, white porcelain and celadon porcelain. In 1957, he was acknowledged as a preserver of the overglaze technique, and was then acknowledged as a Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) in 1961.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

Kato Sekishun (Hoyuken Sekishun 1870-1943)

Born 1870. A favorite of Itagaki Taisuke (famous as a leader of Movement for Liberty and People's Rights), he was given the title of Hoyuken. After opening a kiln for Nagono-yaki ware in 1914, he constructed the Kasumori Kiln, producing raku ware with a distinctive glaze known as "Tatsuta-nishiki". He died in 1943.

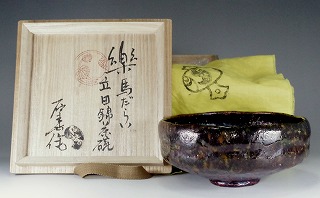

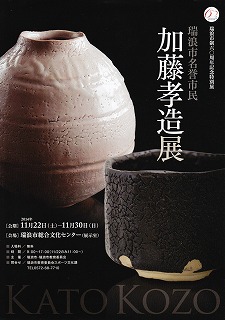

Kato Kozo (1935- )

Worked at Gifu Prefectural Ceramics Research Institute, active as a chief technician while producing his own works on the side. He continued to enter and be chosen for prizes for his works in various exhibitions and was inaugurated as a full member of the Japan Art Crafts Association in 1966.

He received numerous awards such as an award of excellence for his "Iron Glaze Pot" in the Asahi Ceramic Art Exhibition in 1967, the Asahi Prize for his "Iron Glaze Flower Vase" in the 15th Japan Traditional Art Crafts Exhibition in 1968, the Japan Ceramic Society Prize in 1985 and the Tokai Television Cultural Prize in 1994. In 1995, he was acknowledged as a Gifu Prefectural Designated Intangible Cultural Property, and he was chosen for the Chunichi Cultural Award in 1998. In 2010 (22nd year of the Heisei Period), he was designated a Living National Treasure (Nationally Designated Important Intangible Cultural Property) for Setoguro ware.

He often produced works such as traditional Shino ware, Kizeto ware and Setoguro ware using an anagama kiln of a semi above ground style.

Shino glazes are distinctive for their vivid red coloration, and they were known as his most representative works. However, his Setoguro works of recent years also have a sense of presence enough to be on the same level as them or more, and express a dignified taste.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY.

Kato Takuo (1917-2005)

Was born the oldest son of the fifth generation Kato Kobei, and trained at the Kyoto Ceramic Research Center after graduating from Tajimi Technical School. However, he was drafted during the war and was also a victim of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. He was unable to make a comeback for a while, but he resumed creating pottery from 1955, and he was selected for a prize for the first time in the 13th Japan Fine Arts Exhibition in the following year.

In 1961, he received an invitation from the Finnish Government and studied abroad at the Finnish School of Arts and Crafts. During his studies there, he traveled to areas in the Middle East such as Iran and became interested in Persian glaze pottery there. From that time onward, he devoted himself to researching Persian glaze.

After returning to Japan, in 1963 (with a Sancai piece) and in 1965 (with an oil spot tenmoku piece), he received the highest honors in the Japan Fine Arts Exhibition and the Hokuto Award. In 1964, he received the Contemporary Arts and Crafts Award (with a Jun ware piece) in the Japan Contemporary Arts and Crafts Exhibition.

Along with creating pottery, he also often took part in the excavation and research of ruins in Iran on the side. He continued his research on Persian glaze, and after over 20 years of trials, he successfully recreated a type of Persian glaze, lusterware, that had died out since the 17th Century.

In 1982, 1988 and 1995, he received the Ministry of Education Award all three times in the Japan Art Crafts Exhibition. In 1991, he received the Japan Ceramic Society Gold Prize. In 1993 he received the MOA Okada Mokichi Award and his lusterware piece was evaluated highly. In terms of commendations, he was acknowledged as a Gifu Prefecture Important Intangible Cultural Property and a Tajimi City Intangible Cultural Property in 1983. He received the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1988, and in 1955, he was acknowledged as a Nationally Designated Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure), Honorary Citizen of Tajimi City and Honorary Citizen of Gifu Prefecture.

Apart from his lusterware pieces, he excelled in the coloration technology of Sancai glaze and he handled the restoration work of the Sancai in Shosoin at the request of the Imperial Household Agency. He was acknowledged as an Important Intangible Cultural Property due to his Sancai techniques.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY.

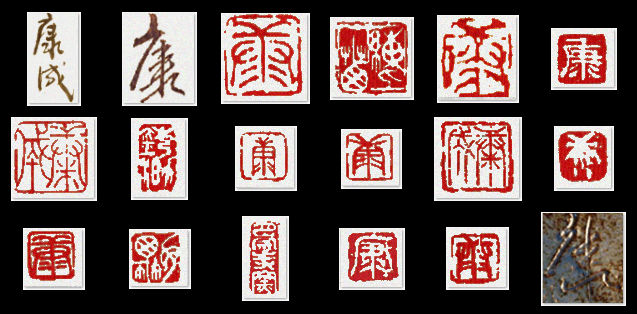

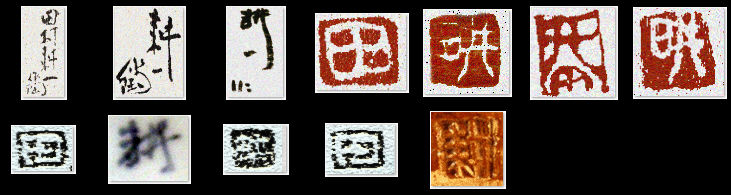

Kato Tokuro (1896-1985)

Kato Tokuro was born the eldest son of Seto potter Kano Sojiro, and as a child displayed a talent for painting in the Nanga style, for composing Chinese poetry, as well as for ceramics, which he practiced under his father. In 1914, he was granted partial rights to his father's round kiln, marking the start of his own kiln construction and ceramics.

In 1918, he married Kato Kinu and took the family name Kato.

He devoted himself to surveying the old Seto kilns and researching traditional Seto techniques, allowing him to reproduce Shino and Oribe ware. In 1929, he founded the Society for the Surveying and Preservation of the Old Seto Kilns. In 1930, he qualified for the Art Aichi Society Exhibition and began associating himself with fellow promoters of folk art movements, such as Yanagi Muneyoshi, Kawai Kanjiro, and Hamada Shoji.

After the war, Kato founded and became the first chairman of the Japan Ceramics Society in 1947, formed the Tori Society together with Ishiguro Munemaro, Kaneshige Toyo, Arakawa Toyozo, Kato Hajime, and others in 1954, and won the Chunichi Cultural Award in 1956.

Tokuro became a director of the Japan Kogei Association in 1957 and a lecturer at the School of Letters, Nagoya University in 1958, but completely withdrew from any public work after the Einin Pot Scandal of 1960. Instead, he devoted himself to the free pursuit of ceramics as an unaffiliated potter. In 1961, he was even bestowed the pen name Ichimusai by poet Hattori Tanpu, after which he signed works Ichimusai or Ichimu.

Moreover, although he was designated as the 1st Intangible Cultural Heritage Technician (today referred to as Living National Treasure), he was stripped of this after the Einin Pot Scandal. A master of potter's wheel techniques, Tokuro recreated the Shino and Oribe ware of the Momoyama period by restoring that period's clays, glazes, and kilns as well as devoted his life to creating reference material on ceramics, such as the Encyclopedia of Japanese Ceramics (Kodansha). After such a long life of contributions to the world of ceramics, he completed his own Akane-Shino in 1977.

His sons include eldest son Okabe Mineo and third son Kato Shigetaka.

The Einin Pot was an earthenware pot that Tokuro had marked as coming from the Einin period (1293–1298) in 1937, which was later designated as a Important Cultural Heritage in 1959 through the strong promotion of Koyama Fujio. It was then discovered that the pot was not from the Einin period but made by Tokuro. Since the pot was included in a ceramics dictionary edited by Tokuro himself, this incident developed into a fraud scandal that shocked all of Japan, but Tokuro's ability to imitate the ceramics of that period so skillfully has also been highlighted since.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 100,000,000 JPY.

Kato Usuke (1915-1981)

Kato Usuke, a potter of Seto and Akazu ware, was born in 1915 as the son of Usaburo the 20th. With his ancestor being the second son of the father of Seto ware, Kato Kagemasa Second Generation Toshiro Motomichi, Fuji Saemon as the first generation, he takes his name Usuke from the 17th Generation Keitoku Jinzo. His teaware products include koseto, setoguro, shino, and oribe among others, and there are many excellent products that could easily fit in with ancient works. Usuke's works are engraved with his signature, "う(U)". He has held solo exhibitions in various parts of Japan, in Los Angeles, and in Czechoslovakia his works are highly regarded, with some of them even being considered works that will be permanently preserved.

Since Kato Usuke is considered the best potter for Seto, he has received many requests to make imitations from the Kamakura period.

In 1959, a vase with the inscription "Einin 2" (1294) was discovered, and it was designated as one of Japan's Important Cultural Properties as a koseto masterpiece from the Kamakura period. However, it was discovered that this work was a contemporary one by the potter, Kato Tokuro (1896-1985), and two years later it had its status as an Important Cultural Property revoked. It was a scandal involving the Art History Society, the Ancient Art Society, and the Administration for Cultural Property Protection, where the cultural official who recommended its designation as an Important Cultural Property took responsibility and resigned.

Koie Ryoji (1938- )

Ryoji is an author known as a potter who has produced a great number of abstract works and who continues to gain recognition not just in Japan, but globally. He holds exhibitions in Japan and all over the world.

He uses materials and techniques for his works that are utterly different and unique. The appeal of his dynamic and yet subtle style is its constant creative urge, pursuing the possibilities of what can be made from clay and fire. At the same time, his touch can also be felt in his smaller works, such as tableware, and his fans are always fascinated by what he will create next.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 1,000,000 JPY.

Kawai Kanjiro (1890-1966)

After graduating from Tokyo Higher Polytechnical School, Kawai worked and studied at the Kyoto Research Institute for Ceramics. In 1920, he built his own independent kiln in Gojozaka (inherited from Kiyomizu Rokubei V), and married Tsune Kawai (née Mikami Yasu) the same year.

His first ceramics exhibition was held the following year at Tokyo's Takashimaya Department Store. From the beginning, he studied ancient Chinese and Korean ceramics, and was highly praised for developing pieces with ever more unique molds, but he held doubts about his style, and temporarily ceased to make pottery. It was around this time he was introduced to Yanagi Soetsu by Mashiko potter Hamada Shoji. In 1926, after wishing for the establishment of a "Japanese Mingei Museum" he instigated the mingei (folk art) movement, along with Hamada, Yanagi, Bernard Leach, Munakata Shiko and others.

He resumed making pottery again in 1929, pursuing "the beauty of use" and undergoing a massive change towards mingei style pieces. In 1937 he won the Grand Prix at the Paris Exhibition Internationale for "Tetsushinsha sokazutsubo", and another Grand Prix at La Triennale di Milano in 1957 for "Shiroji sokaehenko".

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 30,000,000 JPY.

Kawai Takekazu (1908-1989)

Takekazu began studying pottery making under Kawai Kanjiro, his uncle, in 1927, and received his guidance over the course of the nearly 40 years until Kanjiro's death. He inherited mingei techniques such as gosu porcelain, cinnabar lacquerware, and ameyu and kakiyu glazes from his uncle.

During this period, he worked as an assistant to Bernard Leach, who was visiting the Kanetani kiln (Kanjiro's workshop) in 1935, and sought guidance at his side.

In 1964 he traveled to Australia and New Zealand, holding one man exhibitions and classes in Sydney, Melbourne and Wellington. A three man exhibition along with Kanjiro and Kanjiro's son Hiroji was held at Tokyo's Takashimaya Department Store in 1966. In 1978 he toured with a commemorative 50th anniversary pottery exhibition at Takashimaya stores in Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, Okayama and Yokohama.

Much like Kanjiro and Hiroji, Takekazu's pieces have no signature.

Kawakita Handeishi (1878-1963)

A wealthy cotton merchant from Ise born to the Kawakita Kyudaku household, he was separated from his parents and became the head of the family at around 1. He took the name of Kyudaku the 16th, and received training in Zen and so on from his grandmother (what is currently called "emperor studies"). After graduating from Waseda University, he took on his father's occupation, also working as a Hyakugo Bank board member in 1903 before becoming Hyakugo's president in 1919, and its chairman in 1945. He also served as a member of the Mie prefectural assembly.

During this time he also showed a wide ranging talent for ceramics, calligraphy, and painting, particularly ceramics. He began making Raku ware in 1912, and opened a coal furnace at his home in 1929. In 1934 he built a Noborigama kiln of his own design, and held a one man show at Rosanjin's Hoshigaoka-saryo restaurant.

He also formed the "Karahine Kai" group with Kaneshige Toyo and Arakawa Toyozo in 1939, and established the Hironaga Toen studio in 1946.

He put particular effort into tea bowls, but rather than formal molds or expressions he would develop pieces with free expression, using an abstracted Buddha motif in calligraphy and paintings and so on to develop a unique world. They are currently highly valued on the market.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

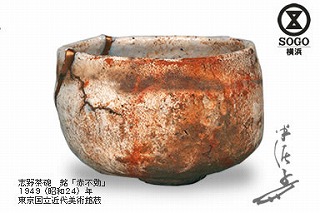

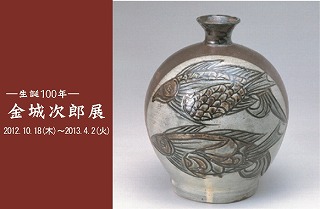

Kinjo Jiro (1912-2004)

In 1924, Kinjo joined craftsman Arakaki Eitoku's pottery workshop in Tsuboya. The same year, he struck up an acquaintance with Hamada Shoji, who was staying in Okinawa; they forged a lifelong friendship.

In 1946, with a goal of reviving traditional Ryukyu pottery, he opened his own kiln in Tsuboya. He began to exhibit in the Crafts division of the Kokuten exhibition of Japanese art in 1955; in 1956, he won the Newcomer's Award, and in 1957, he took home the Kokugakai Prize.

In 1972, he opened a kiln in Yomitan; the same year, he was named an Important Intangible Cultural Asset of Okinawa Prefecture. In 1977, he was awarded the title of Contemporary Master Craftsman by Japan's Minister of Labour. In 1981, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure 6th class; in 1985, he was named a National Important Intangible Cultural Asset (Living National Treasure).

In aiming to revive traditional Ryukyu pottery, Kinjo created ceramics that exhibited a unique warmth, featuring designs such as abstracted fish and shrimp using relief techniques. He developed work that combined function and beauty, and he was highly esteemed as a pioneer in the field of Okinawa ceramic art. He is succeeded by his eldest son, Kinjo Toshio.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

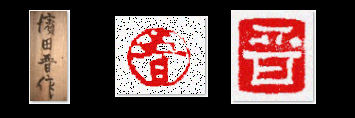

Kiyomizu Rokubei (1738-1799)

In 1738 (Year 3 of the Genbun era), the first Rokubei was born as Koto Kuritaro in Yosumi Village in the Shimakami District of Settsu Province (modern day Takatsuki, Osaka), son of the farmer Koto Rokuzaemon.

During the Kannen era (1748-51) he studied pottery making under Ebiya Seibei in Gojozaka, Kyoto. Afterwards, in 1771 (Meiji era year 8) he became independent and took the name Rokubei. Through the "Kiyomizu" seal he received from his teacher Ebiya Seibei, he came to be called Kiyomizu. He was awarded a seal with the character 清 (pure) to use as his mark as well as the pen name "Gusai".

The first works were primarily tea cups, making use of his specialty characteristic Kaname and Herame patterns. He expanded to create Shigaraki, Seto-lacquer (iron lacquer), Gohon, and blue and white porcelain works. Prince Miyamasa Hitonori of the Myoho Temple commissioned him to make black Raku ware tea cups, for which he recieved the "Rokume" seal. He was thus added to the prince's culture salon, where he became acquainted with artists Maruyama Okyo and Matsumura Goshun, and the writers Ueda Akinari and Murase Kotei. He undertook making literary-styled tea sets for Akinari and Kotei, and in his later years was highly praised for his Ryoro teapots. He died in 1799 (year 11 of the Kansei era). Presently, the 8th generation of Rokubei continues to make pottery.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY (1st Rokube).

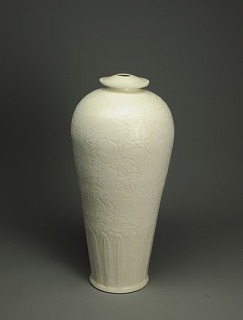

Kondo Yuzo (1902-1985)

Kondo Yuzo was designated a living national treasure and left a remarkable legacy to Japanese ceramics. He was born in 1902 on the very site of this memorial museum, just outside the gate of Kiyomizu Temple. At the age of 12, he entered the training facility of the Ceramics Laboratory to learn to use the potter's wheel. It was there that he met Kanjiro Kawai and Shoji Hamada

Starting when he was 19, he spent three years as an assistant to Kenkichi Tomimoto in Nara.

He established his own studio in the same area when he was 22. There he devoted himself to refining his artistic vision and perfecting his technique.

Thus he was able to reach new heights in his work and gained a reputation as the finest master of the blue and white porcelain known as sometsuke.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

Koyama Fujio (1900-1975)

Committee chairman of the Japan Society of Oriental Ceramic Studies and board chairman of the Japan Kogei Association. After leaving university mid term, he devoted himself to the study of ceramics at Seto and Kyoto, and established himself as a potter in 1925.

However, in 1930 he became an Oriental Ceramics Research Institute employee, suspending his pottery work to devote himself to ceramics and porcelain research. In 1941 he served at the Tokyo Imperial Household Museum, joining in with the work of selecting Designated Cultural Properties. After retiring from the museum in 1961, he started to make pottery again from 1964, and opened a kiln in Toki city, Tochigi prefecture in 1972, producing various works based on existing research into ancient ceramics, such as Karatsu, Bizen, Aoji, and Akae wares.

He left behind numerous achievements in modern ceramics research, both as board chairman of the Japan Kogei Association established due to the success of his name, and while working as a committee member for the Japan Society of Oriental Ceramic Studies and so on.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Kuroda Koryo (Otagaki Rengetsu II) (Meiji period)

His exact dates of birth and death, as well as his birthplace, remain unknown, but he learned pottery from Otagaki Rengetsu and ghostwrote for her during her lifetime. But after her death, from around 1878, he primarily produced shrine offering bowls and so on, naming himself Rengetsu II. From around this time he also used "Koryo san" as his unique pottery seal.

Maeda Akihiro (1954- )

Potter and hakuji (white porcelain) artist born in Tottori prefecture. Acknowledged as a Preserver of the Important Intangible Cultural Property hakuji (a Living National Treasure) in 2013.

Matsui Kosei (1927-2003)

Matsui Kosei

After graduating from university, he was inaugurated as 24th chief priest of the Tsukiso Jodo Temple in Kasama, Ibaraki prefecture in 1957.

In 1959, he began restoring the old kiln at the temple's gate, conducting unique research into ancient pottery from China, Korea and Japan. Further, from 1967 he received training from Tamura Koichi, dedicating himself to the study of Chinese kneading and inlaying techniques in particular. He first exhibited "Renjo te obachi" at the 9th Traditional Kogei Exhibition, receiving an honorable mention award.

Thereafter, he amassed displays at every exhibition, and repeatedly amassed various awards such as the Japan Kogei Association's Presidential Prize in 1971, the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition's top prize in 1973, the 1974 Japan Ceramics Society Prize, the 1975 Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition NHK Members' Prize, the 1986 Fujiwara Kei Memorial Award, a Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1988, the 1990 Japan Ceramics Society first prize, and the 1991 MOA Okada Mokichi grand prize. In 1993 he was acknowledged as a Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (a Living National Treasure).

At first he experimented with natural glazes and denaturing, but gradually Chinese Shu dynasty ceramics left a deep impression on him. He sought out the most unique of these ceramics' kneading techniques, and also developed original works in a modern style using numerous glazes, which are highly valued for the beauty of their coloring.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY.

Miura Koheiji (1933- )

Born with a family background of Miura Kohei as his father and the third generation Miura Jozan, a mumyoi ware pottery artist, as his grandfather, Miura Koheiji also aspired to be a pottery artist and studied under Kato Hajime of Seto ware while attending school.

In 1961, he was selected for a prize for the first time in the Fourth New Japan Fine Arts Exhibition, but from that point onward he continued to receive awards in various exhibitions, primarily in the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibitions. His main awards include the Asahi Shimbunsha Award in the Japan Ceramic Art Exhibition in 1962, an award of excellence in the Traditional Kogei New Works Exhibition in 1967, the Ministry of Education Award in the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 1976, the Japan Ceramics Society Award in 1977, the Japan Ceramics Society Gold Award in 1993, the Grand Prize at the MOA Okada Mokichi Awards Exhibition in 1994, the Japan Kogei Association Holder Award in the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition and the Niigata Nippo Culture Award in 1995 and the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1996. He was acknowledged as a Nationally Designated Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) in 1997.

He founded a world of art brimming with poetic sentiment with works of his original pale celadon glaze poured onto mumyoi pottery clay to make artificial penetrations and then adding akae ceramic decorations. His traditional mumyoi techniques and contemporary color formation has been rated highly both in and out of the country, and he has had many public performances and private exhibitions overseas as well.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Miwa Kyusetsu X (1895 - 1981)

He was born as a child of the 9th Miwa Kyusetsu (Setudo) of the Miwa Kiln of the traditional Hagi Pottery. After he had been disciplined and influenced by his father and his grandfather (the 8th Kyusetsu: Setsuzan), he inherited his family business and in 1927 he inherited the professional name as the 10th Kyusetsu.

He has worshiped and adored works of generations of Kyusetu, and devoted himself to the research of kaolin. Eventually he combined the Hagi clay and white glaze to complete the unique glaze called "Kyusetsujiro". He has also added the character of pottery used at Japanese tea ceremonies to the Korian Korai Dynasty's transfer ware to achieve his own subtle style. Thus, he developed a new personality in the Hagi pottery world and made the foundation for the prosperity of Hagi Pottery today.

After World War ll, he enthusiastically continued to present his works and won many prizes in the contemporary ceramic art exhibitions and the traditional craft exhibitions. In 1961 he was elected as the president of Hagi Pottery Ceramic Association. In 1964 he was certified as a person of cultural merit of the Yamaguchi Prefecture. In 1967 he handed down Kyusetsu to his younger brother and he changed his professional name to "Kyuwa" in his retirement. In 1970, during his later life, he was accredited for his achievements and received recognition as a holder of important intangible cultural heritage (a human national treasure).

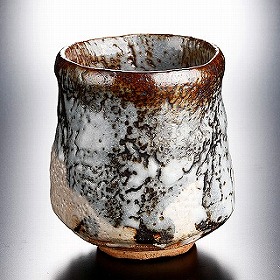

Miwa Kyusetsu XI (1910-2012)

Born the third son of the Miwa kiln's ninth generation Kyusetsu (Setsudo) of Hagi ware tradition, Miwa Kyusetsu studied under his father and older brother (the 10th generation Kyusetsu: Kyuwa) after graduating middle school, and also studied under Kawakita Handeishi.

After a long period of training, he took on the pottery artist name "Kyu" and displayed his work in 1955. He was chosen for a prize for the first time in the Fourth Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 1957, and he continued to be chosen for prizes from that point onward. In 1960, he was nominated for member of the Japan Kogei Association.

In 1967, following the voluntary retirement of his older brother, the 10th generation Kyusetsu, he succeeded the name as the 11th generation Miwa Kyusetsu. After that, he received the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1976 and the Fourth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure in 1982. He was acknowledged as a Yamaguchi Prefectural Preserver of Intangible Cultural Property in 1972 and a Nationally Designated Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1983, both for his techniques in Hagi ware.

He skilfully inherited the traditional korai pottery art and the "Kyusetsu White" glaze style created by his older brother. Furthermore, he developed an openhearted, daring way of making pottery called "Onihagi," which he himself invented during his long period of training, clearly expressing his individuality as the 11th generation Miwa Kyusetsu. He gave his name to Ryusaku and retired, making his pottery artist name "Jusetsu" and continuing to vigorously make pottery.

He passed away due to old age on December 11th.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

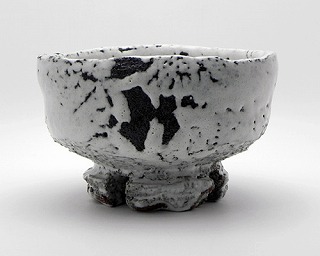

Kitaoji Rosanjin (1883-1959)

Born in Kitaoji-cho, Kamigamo in Kyoto in 1883 (Meiji 16). Rosanjin's birth was a result of his mother having an affair and his father, disgusted by this, committed seppuku suicide 4 months before Rosanjin was born. He had a poverty-stricken childhood and was put into foster care as soon as he was born, being passed on to various loveless adoptive households where he suffered abuse until he settled into the Fukuda household at age 6. One day, while running an errand for the place where he worked, he saw the sign for a restaurant in town called 'Kamemasa' on a paper lantern. The sign bore a picture of a tortoise and some letters drawn in a single brush stroke without the brush leaving the paper, and it captivated him, heightening his curiosity towards art. The man who drew this sign was Takeuchi Seiho, the eldest son of Kamemasa's owner who would go onto become the leading figure of Kyoto's circle of artists that dominated the Teiten and Bunten exhibitions.

In 1905 (Meiji 38), he became a private apprentice to calligraphy artist Okamoto Katei (grandfather of Western style painter, Okamoto Taro) and lived with him for three years. There, he was given the name Fukuda Kaitsu, and over time he gradually began to receive more orders for his work than Katei. In 1907, he became independent from Katei as Fukuda Ōtei. His work prospered and he spent his earnings on calligraphy tools, antiques and dining away from home.

On December, 1910, he traveled to Korea and lived there for three years, working as a clerk in the Printing Bureau of Korea's Administrative Agency. After staying in Seoul for just under a year, he headed towards Shanghai, where he met Wu Changshuo, who was well-known for being the best in the generation in calligraphy, art and seal engraving.

He returned to Japan in the summer of 1912. Half a year later, he was invited as a dining guest by the wealthy Koji Toyokichi of Nagahama and was proposed a place where he can devote himself to calligraphy and seal engraving. Now under the name Fukuda Taikan, he left in Nagahama various masterpieces such as ceiling paintings in small pavilions, paintings on fusuma sliding doors and name engravings.

Then, his wish to become the dining guest for the Shibata household which was frequently visited by Takeuchi Seiho, who he admired and respected, was granted and he requested to make a name engraving for Seiho. Seiho took a liking to his engraving and introduced him to people under his tutelage such as Tsuchida Bakusen, making him increasingly well-known as he became acquainted with the masters of Japan's circle of artists.

In 1917 (Taisho 6), he became acquainted with Benrido's Nakamura Takeshiro and the two became good friends, afterwards running the antique store Taigado together. Taigado then began to serve regular visitors food made from high-quality ingredients served in the antique pottery in the store, and a diner made especially for those with a membership called 'Bishoku Kurabu' was started in 1921 (Taisho 10). Rosanjin himself stood in the kitchen and cooked, and also made the works of pottery used in serving the food. On March 20th, 1925 (Taisho 14), Rosanjin, along with Nakamura, borrowed 'Hoshigaoka-saryo restaurant' in Nagatacho, Tokyo and started a high-quality restaurant open only to those with a membership, with Nakamura as the owner and Rosajin as an advisor.

In 1927 (Showa 2), he invited people ranging from potter Miyanaga Tozan and Arakawa Toyozo to Yamasaki, Kamakura and established a place to research ceramics, Seikoyo, and began working on pottery in earnest.

After the war, he was economically impoverished and lived a life of adversity, but in 1946 (Showa 21), he opened a direct sales store for his own work in Ginza called 'Kadokadobibo' and gained positive feedback, even from Western people staying in Japan as well. In 1954 (Showa 29), under the invitation from the Rockefeller Foundation, he held exhibitions and lectures in various areas in the West, and also visited Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall. In 1955 (Showa 30), his Oribe ware designated him as a Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties (Living National Treasure), but he refused this title.

He passed away at Yokohama City University Hospital due to liver cirrhosis in 1959 (Showa 34).

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 100,000,000 JPY.

Kato Shuntai (1802-1877)

A late Edo period ceramist from Seto. Born into the family of an Akazu potter, his childhood name was Soshiro. Excelling in ceramics from a young age, he followed in his father’s footsteps at the age of 15, beginning to create Ofukei-yaki in 1816. He is said to have received the sobriquet “Shuntai” from Nariharu Tokugawa, the 11th generation Daimyo of Owari-han (Nagoya), at the age of around 30. In response to Tamikichi Kato, a creator of Seto porcelain, Shuntai added the techniques of red painting, Shino-yaki, and Oribe-yaki to his works, and he also excelled at the Mugiwarade style, in which red, white and black designs are applied to the ceramic before baking. In Seto-yaki, there was a traditional style of pottery known as "Hongyo," and Shuntai was one of the last true craftsmen in that tradition. Signing the characters of his name in the bottom of his creations, he bragged about his position as a traditional artisan.

Murata Gen (1904-1988)

Born in 1904 in Kanazawa City, Ishikawa Prefecture. Although originally an aspiring painter, he could not make a living as a painter, thus he came to Mashiko to rely on the renowned Shouji Hamada immediately after the war. He began training as a pupil to practice his ceramic skills in 1944, rose up to a place in Mashiko called Kitagoya, built a furnace and became independent in 1954. Murata transported his completed pottery on his bicycle-towed trailer to the streets of Mashiko for sale, but his life was so difficult that his wife devoted herself to support the family. Murata was also interested in tea ceremony, and the tea cups he made were considerably different from those made by Shouji Hamada. Deceased in 1988. Currently Hiroshi, his third son, has taken his place as his successor.

Accepted for the Modern Ceramic Art Exhibition

Accepted for the National Art Exhibition

Held a personal exhibition at Matsuya Ginza

A committee member of Sankikai's handicraft department

A committee member of Tochigi Prefecture Art Festival's handicraft department

Nakagawa Jinenbo (1953–2011)

Became a potter aged 24 on the advice of his then boss. Went on to build his own bamboo climbing kiln (Jizenbogama) in 1982, after training under Inoue Toya at Kyozangama in Karatsu for three years.

Following this, he mostly showcased his work in solo exhibitions, including at Shibuya Kurodatoen in 1985, and at the Odakyu Department Store the same year.

Nakagawa developed a style of pottery that was unbound by convention, yet respectful of the traditional techniques of Karatsu-ware, such as brush-decorated, mottled, Korean, and brushed slip. He mainly specialized in the production of tea bowls.

In 2000, he succeeded in recreating a tea bowl in the old Okugorai style of Karatsu-ware, and became known as an artist to watch. He died at the age of 58.

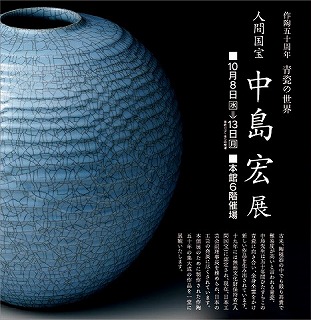

Nakajima Hiroshi (1933- )

He was born on October 1st as the son of Shigeto, his father who had inherited the Nakajima Pottery. After graduating middle school, he helped with the family business. Around this time, his older brother, Takashi, graduated from the Kyoto Institute of Technology and came home, and he began to include avant-garde creations at Nakajima Pottery. In 1965, his "Transformed White Porcelain Pot" received an award in the Saga Prefecture Exhibition. Furthermore, in 1969, when he was around 28 years of age, he built the "Yumino kiln" in the semi below ground style on the remains of the old Yumino kiln, and became independent.

From that point onward, he devoted himself to celadon, showing activity such as receiving prizes, starting with the Encouragement Award in the Japan Traditional Kogei Exhibition in 1977, then the Prime Minister Award in the First Western Japan Ceramic Exhibition in 1981, the Japan Ceramics Society Award in 1983, the MOA Okada Mokichi Grand Prize, the Fujiwara Kei Commemorative Award and the Saga Shimbun Cultural Award in 1996. During that time, he also received acknowledgment as a Saga Prefectural Designated Important Intangible Cultural Property in 1990.

When he first began producing works, he engaged in reproducing Chinese Song celadon. But as he researched old Korean kilns and Chinese Long Quan kilns, he aimed towards celadon that can express the life force of nature, and he established his own original "Nakajima celadon" with works such as those that combine the base material or unglazed parts for high-firing with the glazed parts, and those that have freely expressed penetrations. He also produced pink and purple works, using glaze containing a lot of iron and combining celadon and red glaze.

For contemporary works, he created rotai glaze, which expresses the celadon parts with shades of bitter orange or light green on a dark brown receptacle. He used techniques such as vessel shaping, pottery carving and scraping, and developed in a wide field, from traditional shapes to the abstract. In 2007, he was appointed as a Nationally Designated Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) for celadon.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 6,000,000 JPY.

Nakamura Donen (1876-1937)

Originally, he studied pottery under the 4th generation Dohachi in Kyoto, but he visited and trained in various regions throughout the country as well as Korea and China. Afterwards, he came to Nagoya due to an invitation from Takamatsu Sadaichi, a wealthy merchant there, and he began to create pottery in the same area. He often produced Raku ware and Joseon style tea pottery. He passed away due to illness at 62 years of age.

Around the time of the second generation, Sokuchusai Sosa of the Omotesenke school, gave the name, Yagoto kiln. The fifth generation is currently active.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Nakamura Donen II (1906-1972)

Born January 7th. While studying under his father, he trained in the tea ceremony under the instruction of the tea master Yoshida Josei. In the year Showa 12, he was named successor to his father following his father's death. However, he discontinued his business in the year Showa 18 due to the war and, after training in the tea ceremony once again at Omotesenke, was given the name Yagotokama by the tea master Sokuchusai and began making pottery in the Raku style. He trained under the instruction of Morikawa Nyoshun'an and in the year Showa 40, he won a prize at the Tokai Traditional Crafts Exhibition for a black Raku-style tea bowl he displayed called Amagumo. After that, he was invited to various areas of Japan, including Daitokuji's Zuihoin and Chita's Koboji, to construct kilns and make tea bowls. More so than in his younger years, he grew close with people such as Masuda Don'no and Mingei potter Bernard Leach, beside whom he devoted himself to researching Raku wares and creating marvelous Koetsu reproduction tea bowls. He passed away in April at the age of 67.

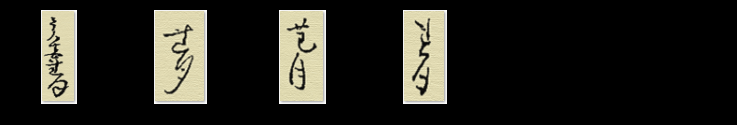

For his artist's seal, he continued to use his father's, as well as a hexagonal seal and a seal reading "Yagoto" written in cursive script.

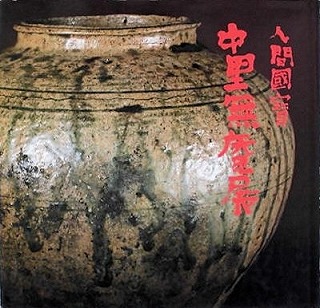

Nakazato Muan (Nakazato Taroemon 12th) (1895-1985)

He was the second son of the 11th generation Taroemon, but his older brother went down a different path and Shigeo came to inherit the house. He gained a grasp of the basic rules of pottery at Arita Technical School, and then at Karatsu Kiln Industry Corporation and Karatsu Brick Corporation after graduation, where he worked as an engineer. After that, he temporarily became an adopted heir of the Mutsuro family, who were lumber dealers, but following his father's death in 1924, he succeeded the name as the 12th generation Taroemon in 1927, and in the following year of 1928, he reconstructed the Ochawan kiln that had been used since the feudal government era and built a new downdraft style coal kiln.

Additionally, in 1929, he began the excavation of the old Karatsu kiln remains. From that point onward, he researched old Karatsu ware, which had died out for a long time, and endeavored to revive it, completing the beating technique and being acknowledged as an Intangible Cultural Property for Karatsu ware in 1955 and receiving the Medal with Purple Ribbon in 1967, the Fourth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure in 1969 and the Western Japan Culture Award in 1970. Furthermore, he was acknowledged as an Important Intangible Cultural Property (Living National Treasure) for Karatsu ware in 1976.

Also, during this time, he entered the Buddhist priesthood at Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, was bestowed the name: Muan, and retired in 1959. In the same year, he had his eldest son, Tadao, succeed the name as the 13th generation Nakazato Taroemon. From that point onward, he devoted himself to creating his original pottery.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 15,000,000 JPY.

13th Nakazato Taroemon (1923-2009)

He was born the eldest son of Living National Treasure Nakazato Taroemon, and inherited the family business. The Nakazato family was for many generations entrusted with the official kiln of the Karatsu Domain.

Aiming for a restoration of old Karatsu ware, along with his father and brother, Nakazato Shigetoshi, his works research a striking technique. This is done by turning the wheel slowly and holding wood in the center, while continuously striking the outside with a board.

He passed away from chronic myelogenous leukemia on March 12, 2009.

Nishioka Koju (1917-2006)

From 1953 he engaged in the study of ancient kilns used for Karatsu ware for 18 years. In 1971 he studied under Koyama Fujio and opened his own waritake climbing kiln, Kojiro kiln; in 1981, under the guidance of Arazawa Toyozo, he opened Koju kiln. In 1999 he opened Kaga Karatsu Tatsunokuchi Kiln in Ishikawa prefecture.

After holding the exhibition "Kojiro Kiln Trio" at Gallery Dojima in 1996, he continued to hold solo exhibitions at the same gallery every year until his death in 2006; in that time he also held his "80th Birthday Exhibition" at the Nihonbashi Mitsukoshi in 1996.

Because he was an independent artist, he does not have a particularly outstanding record of awards; however, he was one of the leading artists of modern Karatsu ware, and possessed enough skill to be called a "Karatsu expert" by Koyama Fujio. He was successful in the restoration of classical techniques such as brush decorated and mottled Karatsu and "kairagi" due to his long years of research of ancient Karatsu kilns. He specialized in tea bowls, and also presented richly textured scenes on rice bowls, vases and pitchers.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 3,000,000 JPY.

Nonomura Ninsei (1655-1673)

After leaving Tamba for the capital and studying at the Awataguchi pottery kiln, he learned techniques for tea caddies in Seto.

After returning to the capital, he made ceramics in front of the gate of the Omura Ninnaji Temple.

We handle supplies used at the same temple.

His style used elegantly colored pottery fired with paintings.

He established the modern mainstream Kyo ware style of Ninseiyaki.

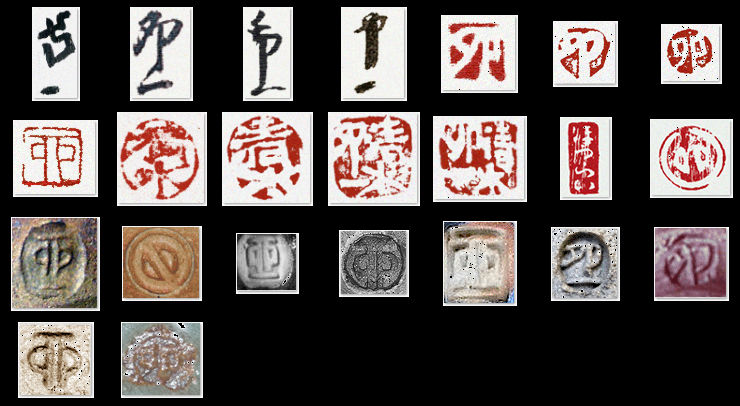

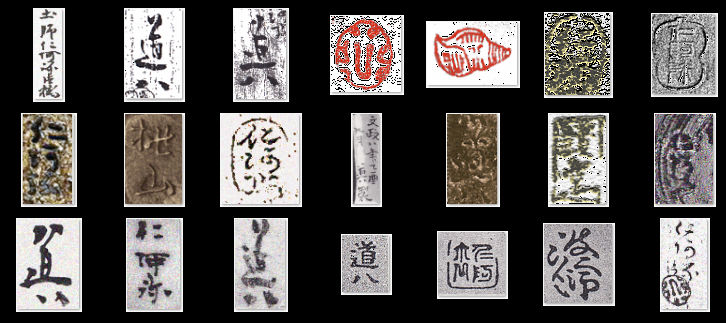

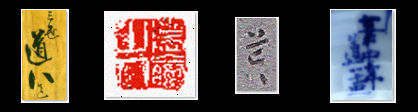

Additionally, he is considered to be the first potter who included not just the name of the kiln but the seal of the artist on his pottery.

As for his pseudonym, "Nonomura" comes from his birthplace, while "Nin" was granted to him by Ninnaji Temple; "sei" comes from his real name, "Seiemon," so he became "Nonomura Ninsei."

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 100,000,000 JPY.

Ogata Kenzan (1663-1743)

Born the third son of Ogata Soken of Kariganeya, a kimono fabrics wholesaler in Kyoto, with Ogata Korin as one of his older brothers.

He studied under Nonomura Ninsei, learning to create pottery. When he was around 37 years of age, he opened a kiln in Kiyotaki, right near the Ninsei Kiln, and as it was located in northwest Kyoto (which in Japanese, is referred to as the cardinal direction of "Inui", a word that can be pronounced as "Ken"), he inscribed the signature of "Kenzan" into his products since then.

His style was influenced by Ninsei, his master, and Korin, his older brother, using many shades of color in the painted earthenware he produced. He also excelled in not only pottery, but art and writing as well, and he moved to Edo in his later years, gaining fame as a writer and pottery artist.

The first generation kenzan had no children or stepchildren. The name of Kenzan has been inherited by subsequent generations, but these successions are not based on blood relations or master to student relationships, and are only through people calling themselves by the name.

The third generation kenzan Shokosai, Miyata Yahei

The fifth generation Kenzan Nishimura Myakuan,

The sixth generation kenzan Miura Kenya,

The daughter of the sixth generation who was supposed to inherit the seventh generation, Ogata Kennyo, made arrangements with fellow older apprentice Bernard Leach and decided that the name of Kenzan will come to an end with the sixth generation in 1969.

Up to 50 potters, researchers, authors, critics etc., concerned added their signatures of approval at the time.

After that, Yamamoto Josen has declared himself as the eight generation kenzan, but this has not been accepted by the Association in Honor of Kenzan.

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 100,000,000 JPY.

Miura Kenya (Ogata kenzan VI) (1821-1889)

- the highest appraised market value of art was over 1,000,000 JPY.

Ogawa Choraku (1874-1939)

Potter of Kiyomizu ware. Studied under Keinyu and Konyu of the Raku family.

From South Kuwa in Tanba Province (modern-day Kameoka in Kyoto Prefecture).

In 1885, he moved to Kyoto and received pottery instruction from Konyu Raku. In 1903, he started a branch family at Konyu's behest and began making pottery in earnest at a kiln in Gojo-zaka. At this time he was granted the name "Choraku" by Master Mokurai, the head priest of Kennin Temple, as well as the name "Choyuken" by Ennosai of the 13th generation of the Urasenke.

In 1910, he moved his kiln to Tenno Town in Okazaki, where he continued to fire Raku ware making use of the best qualities of Keinyu and Konyu while introducing his own touches.