Types of Samurai Sword Fittings

Of all the traditional Japanese art works, the katana, samurai swords, must be the most magnificent. In previous times, our predecessors applied portraits of nature’s harvest and Shinto and Buddhist deities on the katana, which was originally invented as a tool to slay people, as engravings and inlays on its accessories as if to beseech the deities. In time, it became a trade of its own, and promoted the katana to become an ever elegant work of art.

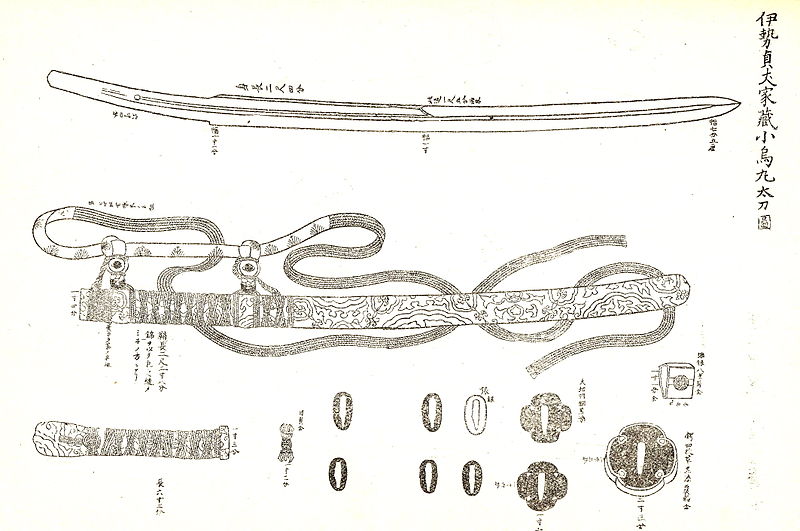

Tsuba

It is a hand guard of Japanese samurai sword "katana" or "tachi". The most popular in sword fittings usually made by inlaid or openworked iron. Generally tsuba has three holes, nakago-ana, kogai-hitsu-ana and kozuka-hitsu-ana, "ana" means "a hole" and "hitsu-ana" means "a hole for storing" in Japanese. The center hale is call as Nakago-ana and nakago is pointing end of sword so nakago-ana is for inserting nakago into hilt.

It is a hand guard of Japanese samurai sword "katana" or "tachi". The most popular in sword fittings usually made by inlaid or openworked iron. Generally tsuba has three holes, nakago-ana, kogai-hitsu-ana and kozuka-hitsu-ana, "ana" means "a hole" and "hitsu-ana" means "a hole for storing" in Japanese. The center hale is call as Nakago-ana and nakago is pointing end of sword so nakago-ana is for inserting nakago into hilt.

The diameter of the average katana tsuba is 7.5-8 centimetres (3.0-3.1 in), wakizashi tsuba is 6.2-6.6 cm (2.4-2.6 in), and tanto tsuba is 4.5-6 cm (1.8-2.4 in).

learn more: Types of tsuba

Kozuka

The kozuka is a short knife attached to a Japanese sword. It is a short blade in and of itself, as well as often being attached to the scabbard of longer katana, such as the uchigatana.

The kozuka is a short knife attached to a Japanese sword. It is a short blade in and of itself, as well as often being attached to the scabbard of longer katana, such as the uchigatana.

In general, the kozuka was used for purposes such as whittling wood, cutting fruit, or other small tasks in the daily life of a samurai, but in an emergency could also be used as a hand weapon or projectile. As with other ornamented swords, the kozuka also came to be an object of fine craftsmanship, raising its artistic value much like with the kogai, which was also attached to a sword's scabbard.

Kogai

The kogai is a decorative tool used for tying and pinning hair. It was an indispensable daily accessory for ladies as well as for samurai, allowing the scalp to be scratched without loosening or ruining a carefully-prepared hairdo. As one of the three attachments for a sword (the mitokoromono: kozuka, kogai and menuki), the kogai was attached to the scabbard in the same way as the kozuka (a small knife inserted into the scabbard) and carried along with the sword. It held an important role as an everyday item for samurai.

The kogai is a decorative tool used for tying and pinning hair. It was an indispensable daily accessory for ladies as well as for samurai, allowing the scalp to be scratched without loosening or ruining a carefully-prepared hairdo. As one of the three attachments for a sword (the mitokoromono: kozuka, kogai and menuki), the kogai was attached to the scabbard in the same way as the kozuka (a small knife inserted into the scabbard) and carried along with the sword. It held an important role as an everyday item for samurai.

Menuki

The Menuki is a part of a sword attached at an eye-catching position at the center of the hilt, which lends its name to the Japanese term for a lively town street, "Menuki Doori". Menuki often featured elaborate designs, like the pommel or the hand guard above the hilt, such as a warlike motif, a family crest, or something more unconventional. In the case of koshirae and itomaki taito hilts it was held in place by the wrapping and served to stop the hand from slipping, but with sharkskin hilts it was exposed on the surface above the wrapping.

The Menuki is a part of a sword attached at an eye-catching position at the center of the hilt, which lends its name to the Japanese term for a lively town street, "Menuki Doori". Menuki often featured elaborate designs, like the pommel or the hand guard above the hilt, such as a warlike motif, a family crest, or something more unconventional. In the case of koshirae and itomaki taito hilts it was held in place by the wrapping and served to stop the hand from slipping, but with sharkskin hilts it was exposed on the surface above the wrapping.

Seppa

Two pair of thin metal washer on either side of the guard (tsuba) of a sword.

Two pair of thin metal washer on either side of the guard (tsuba) of a sword.

Fuchigashira

Where the part of a sword gripped by the hands is known as the hilt, the fuchigashira is the name of the metal fitting affixed to the hilt's front and rear. The one on the side of the hilt with the blade and handguard is known as the fuchi, and the one furthest from the blade is the kashira. Usually made with the same design, there are some old examples of kashira made with horn, but from the Edo period onwards both parts were predominantly made of metal as a matching set. The kashira was made in many ways, including being hammered out of sheet metal, carved from a lump, or cast, but the former was the most common technique. Oblong holes were made on the sides of the kashira and a small eyelet named the shitodome was inserted, through which the wrapping was threaded for attachment to the hilt. In the case of relief carvings, inlayed icons and so on, the fixture was attached from the rear. As for the fuchi, the sheet metal was beat into an eliptical tube, with an opening on one side for the insertion of a copper part cut out of the blade's base in profile. In many cases, there is an inscription in the base of the strong metal reinforcing bolts attached to the fuchigashira.

Where the part of a sword gripped by the hands is known as the hilt, the fuchigashira is the name of the metal fitting affixed to the hilt's front and rear. The one on the side of the hilt with the blade and handguard is known as the fuchi, and the one furthest from the blade is the kashira. Usually made with the same design, there are some old examples of kashira made with horn, but from the Edo period onwards both parts were predominantly made of metal as a matching set. The kashira was made in many ways, including being hammered out of sheet metal, carved from a lump, or cast, but the former was the most common technique. Oblong holes were made on the sides of the kashira and a small eyelet named the shitodome was inserted, through which the wrapping was threaded for attachment to the hilt. In the case of relief carvings, inlayed icons and so on, the fixture was attached from the rear. As for the fuchi, the sheet metal was beat into an eliptical tube, with an opening on one side for the insertion of a copper part cut out of the blade's base in profile. In many cases, there is an inscription in the base of the strong metal reinforcing bolts attached to the fuchigashira.

Tsuka - Hilt

Since the beginning of early modern times, the hilt (the place that you hold in your hand) has been almost exclusively made out of Japanese hackberry wood covered in white sharkskin, with a thread wrapped around it creating a diamond pattern. Formerly, it was made out of materials such as yuzu tree wood or hardwood,; in ancient times it was made out of rhinoceros horn, rosewood, eaglewood, black persimmon, Japanese zelkova, bishop wood, and covered using things such as sharkskin. The long swords of the nobility and guards’ long swords were wrapped in leather instead of thread, and were used on the battlefield by warriors. From the warring states period on, sharkskin and thread wraps became the standard. Sharkskin was also often coated in black lacquer in order to withstand rain and dew. Other than leather and thread wraps, the hilt also used materials such as whalebone, birch bark and hemp rope.

Since the beginning of early modern times, the hilt (the place that you hold in your hand) has been almost exclusively made out of Japanese hackberry wood covered in white sharkskin, with a thread wrapped around it creating a diamond pattern. Formerly, it was made out of materials such as yuzu tree wood or hardwood,; in ancient times it was made out of rhinoceros horn, rosewood, eaglewood, black persimmon, Japanese zelkova, bishop wood, and covered using things such as sharkskin. The long swords of the nobility and guards’ long swords were wrapped in leather instead of thread, and were used on the battlefield by warriors. From the warring states period on, sharkskin and thread wraps became the standard. Sharkskin was also often coated in black lacquer in order to withstand rain and dew. Other than leather and thread wraps, the hilt also used materials such as whalebone, birch bark and hemp rope.

Habaki

The habaki is the part of the sword that is meant to protect the user from touching the sword blade, so it is also called the sayabashiridome (lit. scabbard run stop) or the “protective metal.” It is located between the sword’s edge and its stalk. The inside of the scabbard is delicate, so when it is put into the sheath, it also acts as a stop to prevent the blade from touching the wooden part of the scabbard. Long swords and katanas both have habaki. Very old long sword habaki are set in from the tip of the blade and stop at the bottom of it, but after a while they were made to be set in place by inserting the bottom of the blade into the habaki until it fell in place. Originally it was made by a blacksmith out of iron, but in later times copper, silver, gold and such came into use.

The habaki is the part of the sword that is meant to protect the user from touching the sword blade, so it is also called the sayabashiridome (lit. scabbard run stop) or the “protective metal.” It is located between the sword’s edge and its stalk. The inside of the scabbard is delicate, so when it is put into the sheath, it also acts as a stop to prevent the blade from touching the wooden part of the scabbard. Long swords and katanas both have habaki. Very old long sword habaki are set in from the tip of the blade and stop at the bottom of it, but after a while they were made to be set in place by inserting the bottom of the blade into the habaki until it fell in place. Originally it was made by a blacksmith out of iron, but in later times copper, silver, gold and such came into use.

Saya - Scabbard

The scabbard (the place that you store the sword when you wear it) was made out of cowhide or bamboo in olden times, but came to be generally made out of thin Japanese hackberry wood.

In later years, the thickness was increased, and leather scabbards and lacquer coated scabbards were popularly used. In the middle ages, for the ornamental value, long sword scabbards were made with gilt copper, silver or similar materials such as in brocade wrapped scabbards, hirumaki scabbards and tōmaki scabbards. Guards’ scabbards were made out of leather and wood, also sometimes being adorned with ikakeji, mother of pearl or gold/silver lacquer.

The uchigatanas, short swords and daggers used in early modern times all used lacquer coated scabbards, but the matched long and short swords that warriors used were coated with black lacquer. There are other variants including scabbards that used scratches to prevent slippage. From the mid-Edo era onwards scabbards with metal carvings became popular, and due to influence from the culture of the local leaders, various unorthodox original scabbard coatings were created. These design styles include kairagizame, blue mijin, isokusa, botanmon, mankin, sabiji, mushikui, shuroke, painted bamboo, scarlet mijin, ishime, nanako and rankaku styles. At the end of the Edo era, lacquer sprinkled with gold or silver was frequently used.

Sukashi tsuba

Tsuba (the hand guard on a Japanese sword) were created as a side business by sword-smiths and armorers using their surplus iron for raw materials. Starting with a plate of regular iron, they would cut out a series of openings to create a decorative pattern called a "Kage-sukashi". These patterns likely came to be a source of comfort for samurai during times of war.

Tsuba were categorized according to the title of the artisan, with "tosho tsuba" for those made by sword-smiths, and "katchushi tsuba" for those made by armorers. This practice continued until the end of the Tokugawa period. When the Ashikaga came to power, the shogun brought together artisans who excelled in each of these disciplines. They took the word "Ami" from the name of "Amitabha", which was used by the "Jishu" faith (a sect of the Pure Land Buddhism that arose at the end of the Kamakura period)" that was prevalent at that time, and incorporated it into their own name as a way to gain protection for and to promote their art.

Under the name "Shoami", these artisans experimented with new techniques for making tsuba from the previous era, and produced a number of their own designs.

In addition to conventional kage-sukashi, this era also saw the creation of "sukashi-tsuba", a type of design made by cutting the remaining parts left from the shape of the main pattern.

Tsuba artisans from all over the country came to study the techniques created by the Shoami. After having learned from them, they then dispersed and produced original tsuba that reflected the unique aspects of each region of the country.

These were named after their places of origin, being classified as "Kyo-sukashi-tsuba", "Owari-tsuba", "Akasaka-tsuba", and so on, which are still familiar to this day.

Kinko Tsuba

In the Edo era (1603-1867), when people lived in peace without having to worry about fighting big battles, sword fittings became more decorative than before. They started incorporating a wide range of polychrome metals such as gold, silver, shakudo (alloy of copper and small amount i.e.1.5-10% of gold), shibuichi (alloy of copper and silver, usually less than percent 30) and brass, as well as advanced inlaying and carving skills.

Many decorative styles and techniques were devised in that era. The Bakumatsu (ca. 1840-67) and Meiji eras (1868-1912) saw the pinnacle of sword fittings. In the Bakumatsu era wealthy merchants could outdo daimyo (feudal lords) in financial power so ordered ornate items including up-market materials, while townspeople who were allowed to ware wakizashi (short swords) ordered luxurious fittings for them from metalworkers.

Then Japan opened up to trade with the West and samurai society collapsed, starting the Meiji (literally 'enlightened government') era. When the decree abolishing sword-bearing was issued in 1876, the metalworkers patronized by each clan, lost their jobs. Later, under the leadership of the Meiji government which tried to push ahead a policy of industrialization, the artisans skilled in sword fitting made vases, sculptures and koro (incense burners) with their skills, and sent them to the international expositions popular in the West.

Westerners were impressed and their work earned an excellent reputation. This is no wonder because most metal items in the West back then were nothing but casting made by melting silver or bronze and pouring the result into moulds. No metalworks in the West displayed complex inlaying, varied polychrome alloys or carving. Metalworking arts in Japan then were clearly the best in the world.

The Goto clan

The Goto clan is the most prominent school of sword ornamentation. The progenitor of the clan, Yujo (1449-1512), began service to the 8th Shogun of the Muromachi Shogunate, Ashikaga Yoshimasa (1449-1473), and continued serving the Ashikaga clan until the reign of the third heir, Joshin (1512-1562), who is said to have died in battle. The Ashikaga shogun family later falls into decline, but the Goto clan's fourth heir, Kojo (1529-1620), continued on to serve Oda Nobunaga and became involved in the world of finance; Nobunanga honored Kojo in 1581 with a position creating ooban and balances, and Kojo was appointed to the same position by Hideyoshi Toyotomi. The Goto clan fell into an age of hardship in its sixth generation, with Eijo (1577-1617), alongside the Toyotomi clan, which had appointed the Gotos to government posts; the house of Tokugawa, however, took them on, removing them from danger. The Gotos went on to prosper for nearly 400 years, until the end of the Tokugawa Period, and were not only dominant in the world of Japanese engraving, but successful in financial affairs, politics, art, and more..

Tosho tsuba

The Tosho tsuba ("swordsmith tsuba") is a type of steel tsuba with a rounded outer ring and small openwork, known for its well-tempered jigane (soft steel) and the uncomplicated nature of the openwork. It is said that Tosho tsuba were produced by swordsmiths as a hobby, though this is in dispute.

Katchushi tsuba

The standard interpretation of the definition of a Katchushi tsuba is that it is a tsuba made by an armorist (katchushi), but whether or not the tsuba were made by someone who actually created armor is dubious. A more credible theory is that the name was taken from the plum and cherry blossoms that are common in the openwork of this type of tsuba; such blossoms are often found on the edges of the face guards on suits of armor. It is more natural to conclude that the makers of this type of tsuba included all blacksmiths, not just armorists. One family of armorists known to have actually created tsuba is the famed Myochin school, which prospered first in Kyoto and later expanded across the country. Their forefather is said to be the legendary statesman Takenouchi no Sukune, and they are said to have been known for the armor they created for generations in the Kamakura Period. Even now, their descendants continue to create outstanding work, such as the Myochin Hibashi, or "musical chopsticks."

Onin tsuba

The Onin tsuba are named for the Onin War, which took place around the time of their creation. In terms of style, they draw from the tradition of the Katchushi tsuba, but at the same time, they also have similarities to the Kamakura tsuba: created from a thin plate, and tempered with a hammered finish. Brass inlay is applied over the jigane soft steel body, hemming the seppa-dai and holes.

Heianjo tsuba

Heianjo tsuba have a similar style to the Onin tsuba as well as others of the same period. They were produced for a long interval, from the late Muromachi to the early Edo Period, which is reflected in the changes seen in their quality over time. The name "Heianjo" is taken from a location in Kyoto. It boasts a round body and typically has brass inlaid and openworked arabesque patterns, flowers, and family crests.

Kamakura tsuba

Kamakura tsuba take their name from the intense similarity between their engraving style and Kamakura-bori carved wood lacquerware. Kamakura tsuba were neither made in the Kamakura Period nor bear any relationship to the place.

Kanayama tsuba

Kanayama tsuba are generally considered to have been made around the Owari and Mino Provinces, by a group of former armorists and swordsmiths who changed occupations in the latter half of the Muromachi Period. Their production can be traced back to the mid-Muromachi Period; the Warring States period is considered to be their golden age. They have a blackiron coloration and a protruding roughness around the rim that is pleasant to the fingers. While these tsuba are traded at a high value in enthusiast circles, the pieces from the Edo Period onwards begin to adopt Owari openwork techniques and eventually take on a more commonplace style.

Kyo-sukashi tsuba

Kyo-sukashi tsuba are openwork tsuba that were produced in the Yamashiro Province (currently Kyoto). In contrast to the stout and rough Owari-sukashi tsuba, Kyo-sukashi tsuba are elegant and elaborate with highly refined patterns. None bear the name of the creator.

Owari-sukashi tsuba

Along with the Kyo-sukashi tsuba, the Owari-sukashi tsuba is the greatest among Sukashi tsuba (tsuba with openwork designs). They are estimated to have been produced mainly from the latter half of the Muromachi Period through the Momoyama Period to the beginning of the Edo Period. The primary characteristic of Owari-sukashi tsuba is their strong, thick feel, which contrasts with the Kyo-sukashi tsuba, and their combat-first style, which gives them good weight distribution and a lustrous blackiron color.

Akasaka tsuba

The progenitor of the Akasaka tsuba, Tadamasa, originally created Kyo-sukashi tsuba, but he is thought to have moved to Edo and settled in Akasaka, where he began making tsuba in a new style. Akasaka tsuba are characteristically round, with a round rim of openwork.

Yamakichi tsuba

Yamasaka Kichibei is thought to have produced tsuba and war helmets in Owari Province's Kiyosu. It is believed that he worked for Oda Nobunaga, though this idea remains unproven; nonetheless, it is certain that he was alive during Nobunaga's era. His signature shortens his name to "Yamakichibei", which is the origin of the name "Yamakichi tsuba".

Kanaie

Tsuba makers during the Momoyama Period. They are said to be the originators of efu-style tsuba: tsuba engraved with images of landscapes, people, and religious figures using sukidashi-takabori techniques. The tsuba are inlaid lightly with gold and silver and come in a wide variety of shapes, such as rounded squares and quince blossoms. They are signed "Josho Fushimi ju Kaneie" and "Yamashiro Kuni Fushimi ju Kanaie". They are said to have worked either in the Muromachi or Momoyama Period, but from the "Fushimi ju", it is most appropriate to say they lived after the construction of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's Fushimi castle (in 1594). They are renowned for being among the first famous tsuba makers to work after the tsuba became independent from the sword and became an art of its own. Works of the Kanaie included in the Important Cultural Properties of Japan are the Daruma, Bishamonten, Kasugano, and Enkouhogetsu tsuba.

Nobuie

The Nobuie were tsuba makers in Owari at the end of the Muromachi Period and are famous alongside the Kanaie. Nobuie contrasts the grace of Kanaie with its grandeur. The house moved to Kiyosu at the invitation of Oda Nobunaga and worked there on their tsuba. Their work usually contains hairline carvings of kanji characters and well-known figures on thick steel; on rare occasion, they will feature simple Owari tsuba-style openwork and sukibori carving. They are no relation to the 17th-generation Katchushi Myochin member Nobuie.

Akita Shoami

Akita was a castle town of 200,000 koku (approx. 36,000 cubic meters) run by the Satake house in the Dewa Province, and was once known as Kubota. It is the area where the Shoami school worked, with Shoami Denbei (1651-1727) gaining particular renown. Much of his work uses "shakudo," a copper-gold alloy, or "shubuichi," a copper-silver alloy, skillfully combined with curved geometric patterns. Denbei left behind many bold tsuba with outstanding designs.

Shonai tsuba

Shonai was a castle town of 140,000 koku (approx. 25,000 cubic meters) belonging to the Sakai house; it is currently known as Tsuruoka city in Yamagata. Sato Yoshihisa went to Edo to study the techniques of the Nara school; he returned to Shonai and educated the famous Tsuchiya Yasuchika (his son-in-law), Watanabe Arichika, and Ando Yoshitoki. Katsurano Sekibun also went to Edo in his youth and studied under the Hamano house; he went on to be employed by the Shonai Domain.

Sendai

Sendai was a castle town of 620,000 koku (approx. 112,000 cubic meters) belonging to the Date house; it was a bastion of culture and art from the time of its founder, Date Masamune. Kusakari Kiyosada was born in Sendai; he moved to Edo in the Meiwa era, where he studied under the Omori house. He later went on to work for the Date house. His style is unique for its novel representations of war fans and hemp leaves with Sendai style inlays.

Aizu Shoami

Aizu, in the Mutsu Province, was a castle town of 230,000 koku (approx. 41,000 cubic meters) owned by the Matsudaira house, home to many metalsmiths. A Shoami school known as "Aizu Shoami" prospered here. It produced many tsuba that are sub-par, but among those known for being reasonably skilled are Shoami Ikko, Shoami Kanesuke, and, from other schools, Kato Hideaki (Ishiguro school), and Kato Akichika (Yanagawa school). There is also Tanaka Kiyotoshi, who went to Edo and attained great success.

Mito

Mito was one of the castle towns that belonged to the Tokugawa Gosanke and was 350,000 koku (approx. 97,000 cubic meters) in size. Many metalsmiths worked there, especially in the late Edo Period; they able to use a variety of metals and techniques to create a number of ingenious pieces. The Sekijoken and Ichiryu schools were particulary prominent.

The Echizen Province

The Fukui Domain in the Echizen Province was a prosperous castle town of the Matsudaira house, and was 350,000 koku (approx. 63,000 cubic meters) in size. In this area, Kinai, Myochin, and Akao schools are particularly famous.

Kaga

Kanazawa, Kaga, was a castle town of 1,000,000 koku (approx. 180,000 cubic meters) that belonged to the Maeda house; it was a place where dazzling culture blossomed. Most of the tsuba produced here were more delicate than rugged. The Maeda house invited the Goto family (Kenjo, Teijo, Etsujo, and Enjo) to Kaga and provided them with land and a residence, which led to the flourishing of the school known as "Kaga Goto" here.

Mino

Mino has been a crucial transportation hub since ancient times; due to its proximity to Kyoto, the art of engraving was also highly developed here. In professional appraisals, pieces made prior to the Momoyama Period are known as "Ko-Mino" ("old Mino"), and all produced after that as known as "Mino-bori" ("Mino engravings"). Mino-bori is characteristic for its use of either shakudou copper-gold alloy or "yamagane" impure copper; hardly any untilize iron or steel. They are often made with designs of autumn flowers. The seppa-dai and the rim are usually left undecorated; only the rest of the tsuba is engraved.

The Kitagawa School

Soheishi Soten lived in the Hikone domain in the Omi Province and for the most part made only tsuba. He used nikubori (relief carving) and inlaid colors to create images of warriors and ascetics in his tsuba. His work became extremely popular and took the world by storm.

Choshu tsuba

In the Choshu Domain, tsuba making was promoted to provide exports to other domains as a source of revenue. The resulting number of tsuba makers and the volume of their work held its own against the eastern Aizu, and Choshu came to be known as Aizu's western counterpart. The variety of the Choshu tsuba is so great that its style cannot be categorized and there is no paricular group with a distinguishing feature, but its defining schools are Kawaji, Nakai, Okamoto, Okada, Kaneko, Nakahara, Fujii, Inoue, and Yazu, which all became comparatively well-known.

The Hizen Province

Now known as Saga Prefecture, the Hizen Province was divided between the territory of Saga's Nabeshima house (330,000 koku, or approx. 59,000 cubic meters), Hirado's Matsuura house, and the houses of Doi and Mizuno in Karatsu. Saga's Jakushi house and Yagami's Yagami school are well known tsuba makers in the area. Also, the unique "Nanban tsuba", uniquely designed after works of the Qing Dynasty, came into vogue in Nagasaki, the Edo Period's only portal to the outside world.

The Higo Province

For the duration of the Edo Period, the Higo Province was ruled by the Hosokawa house. The progenitor of the Hosokawas, Hosokawa Tadaoki (Sansai), was not only a famous commander but a known master of the tea ceremony, well versed in chaji formal teas and the composition of waka poetry; he became one of the Rikyu Shichitetsu, the seven disciples of famed tea master Sen no Rikyu. Though the Higo Province was far removed from Edo and Kyoto, it was known for its highly refined culture. It turned out many famous tsuba makers; its "Higo tsuba" are lauded by modern enthusiasts.

The Satsuma Province

This Shimazu clan ruled the 770,000 koku (approx. 139,000 cubic meters) of the Satsuma Province for generations. The province produced many pieces with powerful designs. The Oda school was patricularly well-known within the area, with Naokata, Naonori, Naonori and Naokata gaining renown.