Key person of chanoyu

The origin of Matcha

When envoys to the T'ang Dynasty and traveling monks brought tea seeds back home with them from their travels, "tea" made its first appearance in Japan. At first, in Japan as in other places, tea was used as a medicinal product, and was drunk only among the nobility and powerful classes. The method of brewing matcha first appeared in Japan in 1191, when Eisai, founder of the Rinzai school of Buddhism, returned to Japan from China, bringing tea seeds with him, which were then crushed into a fine powder and mixed with hot water. Presenting the shogun at the time, Minamoto no Sanetomo, with a cup of tea and his treatise on the uses of tea, the "Kissa Yojoki," Eisai expanded the practice of drinking tea even further, reaching as far as samurai society. During the Nanboku-cho period (1336-1392), the consumption of matcha continued to spread, reaching as far as the general public. Then, during the Muromachi (1336-1573) and Azuchi-Momoyama Periods (1558-1600), Murata Juko, Takeno Joo, and Sen no Rikyu developed new practices of tea drinking etiquette, through which the "wabi-cha" style of tea ceremony achieved prominence. Subsequently, it began to spread among the samurai class, and what is now known as the "tea ceremony" came into being. In recent years, Japanese food has come to be consumed in countries around the world, with the help of the health boom. Similarly, the attraction of Japanese tea, and of matcha, has come to be widely recognized. Indeed, the word "matcha" is now used as a commonly understood term across the globe.

Murata Juko (1423-1502)

Takeno Joo (1502-1555)

Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591)

Furuta Oribe (1543-1615)

Honami Koetsu (1558-1637)

Kobori Enshu (1579-1647)

Murata Juko - The founder of Wabicha

Murata Juko (1423-1502) is known as the founder of wabicha. While the exact details of his life story are unknown, he is said to have made his beginnings as a priest from Nara. However, it seems that he later resided in Kyoto, where he made his fortune in commerce.

Murata Juko has come to be known as the father of wabi-cha based on the pivotal document which he left behind, "Kokoro no Fumi" (Letter from the Heart).

In "Kokoro no Fumi," Juko wrote of "obfuscating the boundary between Japan and China," referring to the boundary between tea utensils imported from China (karamono) and domestically produced Japanese tea utensils. Up until that time, karamono had largely dominated in tea ceremonies, but Juko was concerned with achieving harmony between the two in order to create a new beauty. Moreover, he wrote, "the moon, too, is disagreeable without the rift between the clouds," stating that a moon which appears and disappears behind the clouds was more beautiful than the pure white shine of the full moon. It has been argued that wabi-cha was born out of Juko's enjoyment of this type of insufficient beauty (wabi sabi).

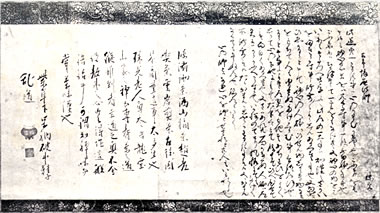

Kokoro no Fumi - Letter from the Heart

This is the opening section of the writing from Juko Murata, the founder of the Wabicha style of Japanese tea ceremony, for his apprentice, Harima Furuichi. Juko says that self-conceit and self-attachment are the biggest obstructions for the way of the tea ceremony. He continues by saying, "It will not do to envy the masters and look down on the beginners." People have antipathy towards those who are better than them and look down on beginners because they have self-conceit and self-attachment. He explains, "It is important to feel admiration for the skills of those who are better, and also to help the beginners with their training."

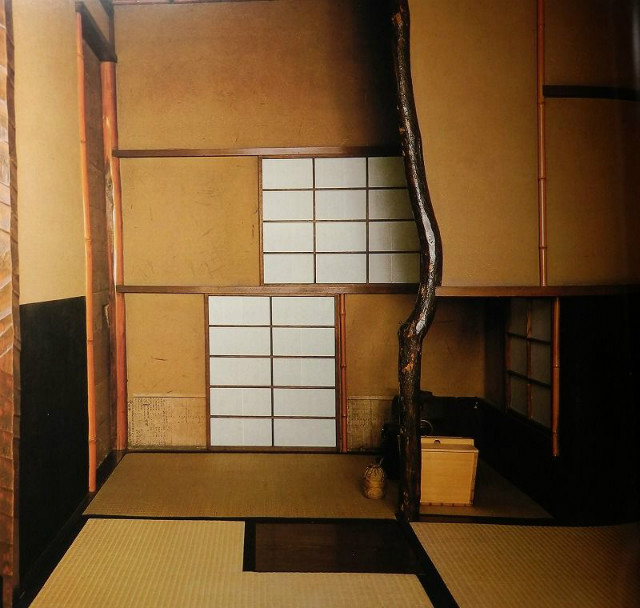

Soan - Juko's tea room

The tea ceremony room that is said to have been Juko Murata's has a brim on the entrance, the interior is made up of one room, and space is four and a half tatami mats wide, which includes the hearth. The tea ceremony that takes place in this room, which may remind you of a house in the mountainside, is called the Soan tea ceremony. This meant it was Wabicha style.

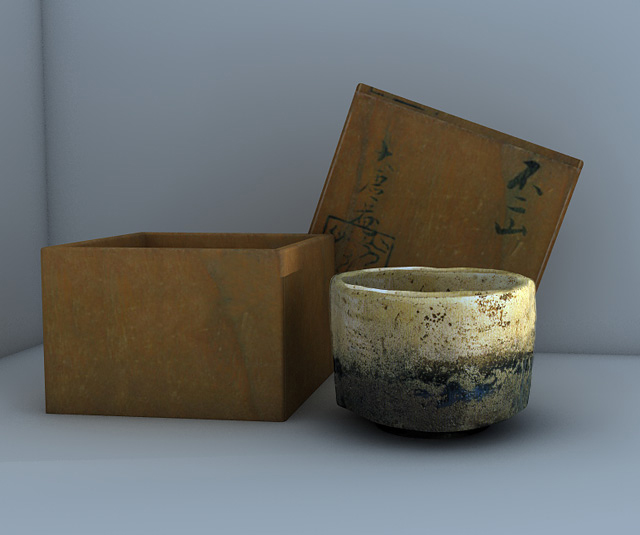

Juko Chawan

In the shogun family of the Muromachi period , the Tenmoku tea bowl or celadon porcelain tea bowl of Longquan were appreciated because of the tea drinking culture that valued Tang-style tea bowls, but Juko praised plain, cheap-looking, bowls and established the tea ceremony using such plain tea utensils. His "wabi-spirits" was inherited to masters of tea ceremony such as Sen no Rikyu later.

Takeno Joo

Takeno Joo (1502-1555) was an Sakai City merchant. While he was named Nakaki, he was also known commonly as Shingoro, later took the name Daikokuan. In Sakai City, he ran a business by the name of Kawaya (leather shop), which is believed to have most likely sold items such as armor and helmets. While the Takeno household was the most prosperous household in Sakai, Joo went to Kyoto in his youth and immersed himself in the world of renga (collaborative poetry). It is thought that this basic foundation in renga had a significant influence on Joo's tea ceremony. Upon returning to Sakai City, Joo moved to the Nanshu-ji Temple and trained under the Zen priest Dairin Soto. There, he experienced an awakening about the tea ceremony, which helped him cultivate his philosophy of chazen ichimi, a way of thinking which posits the unity of tea and zen. While Joo is said to have owned 60 types of special tea utensils, he also succeeded in infusing the tea ceremony with the beauty of pure, plain wood by opting for a plain wood well bucket to use as his water jar, whittling a tea spoon for himself out of bamboo, and cutting a lid saucer for himself out of green bamboo, among other things. This creative approach to tea ceremony was passed down to Joo's disciple, Sen no Rikyu, and helped the tea ceremony achieve even greater prominence.

Takeno Joo (1502-1555) was an Sakai City merchant. While he was named Nakaki, he was also known commonly as Shingoro, later took the name Daikokuan. In Sakai City, he ran a business by the name of Kawaya (leather shop), which is believed to have most likely sold items such as armor and helmets. While the Takeno household was the most prosperous household in Sakai, Joo went to Kyoto in his youth and immersed himself in the world of renga (collaborative poetry). It is thought that this basic foundation in renga had a significant influence on Joo's tea ceremony. Upon returning to Sakai City, Joo moved to the Nanshu-ji Temple and trained under the Zen priest Dairin Soto. There, he experienced an awakening about the tea ceremony, which helped him cultivate his philosophy of chazen ichimi, a way of thinking which posits the unity of tea and zen. While Joo is said to have owned 60 types of special tea utensils, he also succeeded in infusing the tea ceremony with the beauty of pure, plain wood by opting for a plain wood well bucket to use as his water jar, whittling a tea spoon for himself out of bamboo, and cutting a lid saucer for himself out of green bamboo, among other things. This creative approach to tea ceremony was passed down to Joo's disciple, Sen no Rikyu, and helped the tea ceremony achieve even greater prominence.

Haku tenmoku chawan

The tea bowl with white Tenmoku glaze is said to have been owned by Joo Takeno. Although its name is Tenmoku glaze, it is not as rigid as the tea bowls with Kensan glaze. It is rounded on the sides in a bowl shape. Until recently, they were thought to have been made in the Mino Province, but fragments similar to these were found recently in the lowers kilns in Onada, Tajimi City. Therefore, the likelihood that these tea bowls were made in the same kiln has arisen. It was handed down from Jouou Takeno to his grandson, Shinuemon, and to Tokugawa Yoshinao.

From the data, haku tenmoku chawan used in tea ceremony party by Oda Nobunaga in Nov 1573 and used a few times in other tea ceremony from the last years of medieval to the early years of modern.

Take Chashaku

Takeno Joo's bamboo tea spoon. It is a beautiful tea spoon that is long and thin, the Tsuyu at the point is wrapped perfectly. There is an evident engraving that says "Ikkansai" near the Kiridome. Sen Sotan gifted the case.

Sen no Rikyu

About 500 years ago, in what is now Osaka Prefecture's Sakai City, Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), as the oldest son, became the head of his family at the young age of 19, following the death of his father. Later, he went on to achieve success in commerce and became an influential merchant. He began studying tea out of necessity in his social relationships with his fellow merchants, but would go on to devote himself to it.

Rikyu is famous for his service as the master in charge of tea ceremony for the prominent warriors Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi in the turbulent age. The position of tea master included multiple responsibilities, including serving the shogun's family and various daimyo, making the preparations for tea ceremonies, decorating tatami rooms, and evaluating and purchasing artwork.

Nobunaga employed three tea masters including Rikyu, but this may have been in order to make political use of the economic strength and knowledge which they possessed.

Nobunaga's subordinate military commanders also had a taste for drinking tea, and one of them, Hideyoshi, became close with Rikyu. In 1582, after Nobunaga's assassination in the Honno-ji Incident, Hideyoshi's succession and subsequent unification of the country became a significant turning point in Rikyu's life. As Hideyoshi was exceptionally passionate about the tea ceremony, the great success of the practice in the Azuchi-Momoyama Period was due in great part to his influence. One might say that it was due to the backing of such a powerful ruler that Rikyu's style of tea ceremony would go on to become the standard style.

While other styles of tea ceremony employed pottery and utensils imported from China (karamono), and took place in drawing rooms which valued strict formality, Rikyu did not partake in the buying and collecting of these special products. Even after rising to a unique position as Hideyoshi's tea master, he continued to adhere to wabi-cha, a style which requires the spirit of a tranquil heart, and refined it, transforming it into the mainstream style of tea ceremony.

Because Hideyoshi used tea politically, he held tea ceremonies quite frequently. One of the reasons, among others, that he favored tea ceremonies was that they facilitated confidential meetings, and allowed him to invite guests into private, close quarters, encouraging them to develop feelings of intimacy by making and treating them to tea.

As one of his close associates through his employment as tea master, Rikyu's relationship with Hideyoshi became one of intimate friendship. Of the tea ceremonies that Hideyoshi held, the most famous was that held in Kyoto's Kitano Tenmangu Shrine in 1587, the Great Tea Ceremony of Kitano (Kitano Daisanoe). It is said that while over 300 seats divided the shrine's compound, because anyone was allowed to participate, over 1000 people attended. It was Rikyu who managed this grand ceremony, which served as a fruitful opportunity not only to spread the culture of tea ceremony, but to spread Hideyoshi's influence, as well.

However, four years later, the Rikyu's life came to a very sudden end. Having angered Hideyoshi, he was ordered to commit seppuku, thus putting an end to his 70 years of life.

Following Rikyu's death, his descendents formed the three Senke schools of tea ceremony: omote-senke, Ura-senke, and Musakoji-senke.

The names of these three schools are derived from the locations of their corresponding tea rooms. As Fushin'an is the name of the tea room where Rikyu held his ceremonies, this one is known as omote (front) senke, while the one located behind it, Konnichian, is Ura (back) senke. Kankyuan, after the common name of the street on which it was located, continues to be called Mushakouji-senke even into the present. The spirit of Rikyu's tea ceremony has been inherited by these three schools, and they continue to carry it on well into the modern period.

Furuta Oribe

Among Sen no Rikyu's followers, seven people are thought to have been particularly excellent. One of those seven was Furuta Oribe (1543-1615). Oribe was a military commander, and also the lord of a province.

When Sen no Rikyu was sentenced to death by the Shogun Toyotomi Hideyoshi, it is said that before he died, as he was being escorted across the Yodogawa river by boat, Furuta Oribe was seeing him off from a short distance away.

At that time, Sen no Riykuu was an outlaw who had incurred the ire of the most powerful person in Japan, so if anyone had noticed him seeing Rikyu off, Oribe might have been charged with similar crimes. He was risking his own life by sending Rikyu off in this way, but this kind of act of loyalty toward the tea master to whom he owed so much was typical of Oribe.

Sen no Rikyu was so moved by this that he created two bamboo scoops, called "Yugami (twist)" and "Namida (tears)", as posthumous works. "Namida" was given to Furuta Oribe as a gift. Legend has it that Oribe selected "tears" for his memorial tablet for Rikyu, and after making a blackened bamboo flute, continued to pay respects to him beside an open window.

Hideyoshi, who had sentenced Sen no Rikyu to death, was known for his love of tea; the large number of famous tea utensils he had collected, and the number of tea ceremonies that he held, made him known as the military commander who contributed the most to the popularisation and development of the tea tradition. Hideyoshi entrusted the reform of the tea ceremony to Oribe. The tea ceremony that Sen no Rikyu had taught him was simple and frugal, and the utensils used were also austere, but Oribe built up his own new tea ceremony on the foundation of that ceremony. He passionately collected and created tea-related works such as architecture, landscape gardening, and tea utensils, bringing about a trend known as "Oribe style". His works conveyed a feeling of loveliness in imbalance; a playfulness that comes from deliberately twisting the shape of things; a discordant aesthetic, for example, patching together a tea bowl that had been deliberately broken to highlight the beauty present even in scars. The tea bowls that Oribe used gained fame during an era that demanded a new system of values, known as "hyouge mono", meaning "jocular things".

In this way, he was able to create a different kind of tea ceremony to Sen no Rikyu's.

After Hideyoshi passed away, Oribe was granted the right to own land by Tokugawa Ieyaso at the battle of Sekigahara, but during the Osaka no Jin (siege of Osaka) he was brought under suspicion of secretly organising a rebellion with Toyotomi, and was ordered to Seppuku, commit ritual suicide. He ended his life without a single word of protest.

|

Among the schools of tea ceremony there are not just the three schools that have Sen no Rikyu as their source (Omote senke, Urasenke, Musakouji senke) but also other styles. Among these is Oribe style, as well as Enshu style, Sekishu style and others that began with Furuta Oribe.

Honami Koetsu

Born in Kyoto, Honami Koetsu was a multi-disciplinary artist of many faces: a craftsman, calligrapher, painter, publisher, gardener, and maker of Noh masks. Known as the da Vinci of Japan, he had an excellent sense of design and left numerous masterpieces in all artistic genres. In the world of calligraphy, Honami is considered to be one of the three great calligraphers of the Kanei era alongside Nobutada Konoe and Shokado Shojo. He is the founder of the Koetsu style.

The Honami family was a high-ranking family of leading businessmen. The family had been well-known as sword connoisseurs since the time of Ashikaga Takauji, and their main patron was Maeda Toshiie of Kaga Province. Koetsu acquired a highly discerning eye for all manner of craftsmanship through exposure to the family business from an early age. He was versed in the techniques of many crafts, including woodworking, metalworking, lacquer, leather crafts, makie lacquer, dyeing and weaving, and mother of pearl (shell crafts), in addition to the production of the collars and sheathes for swords (production processes that are separate to swordsmithing). Later, Koetsu was freed from the family business when his father established a branch family. Based on the craft skills that he had acquired, he started to produce artworks that reflected the culture of waka poetry and calligraphy, which he had admired and studied.

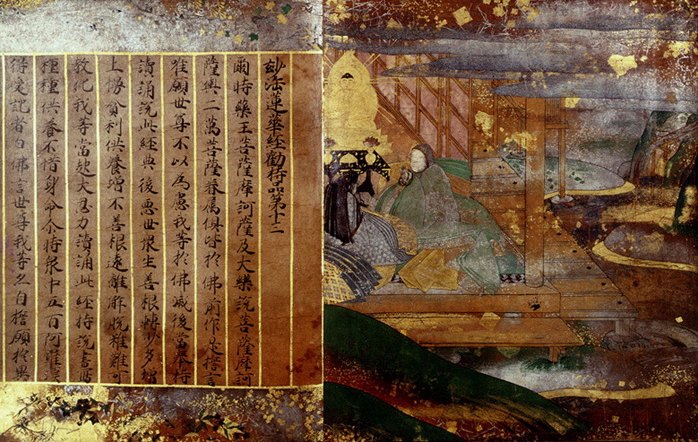

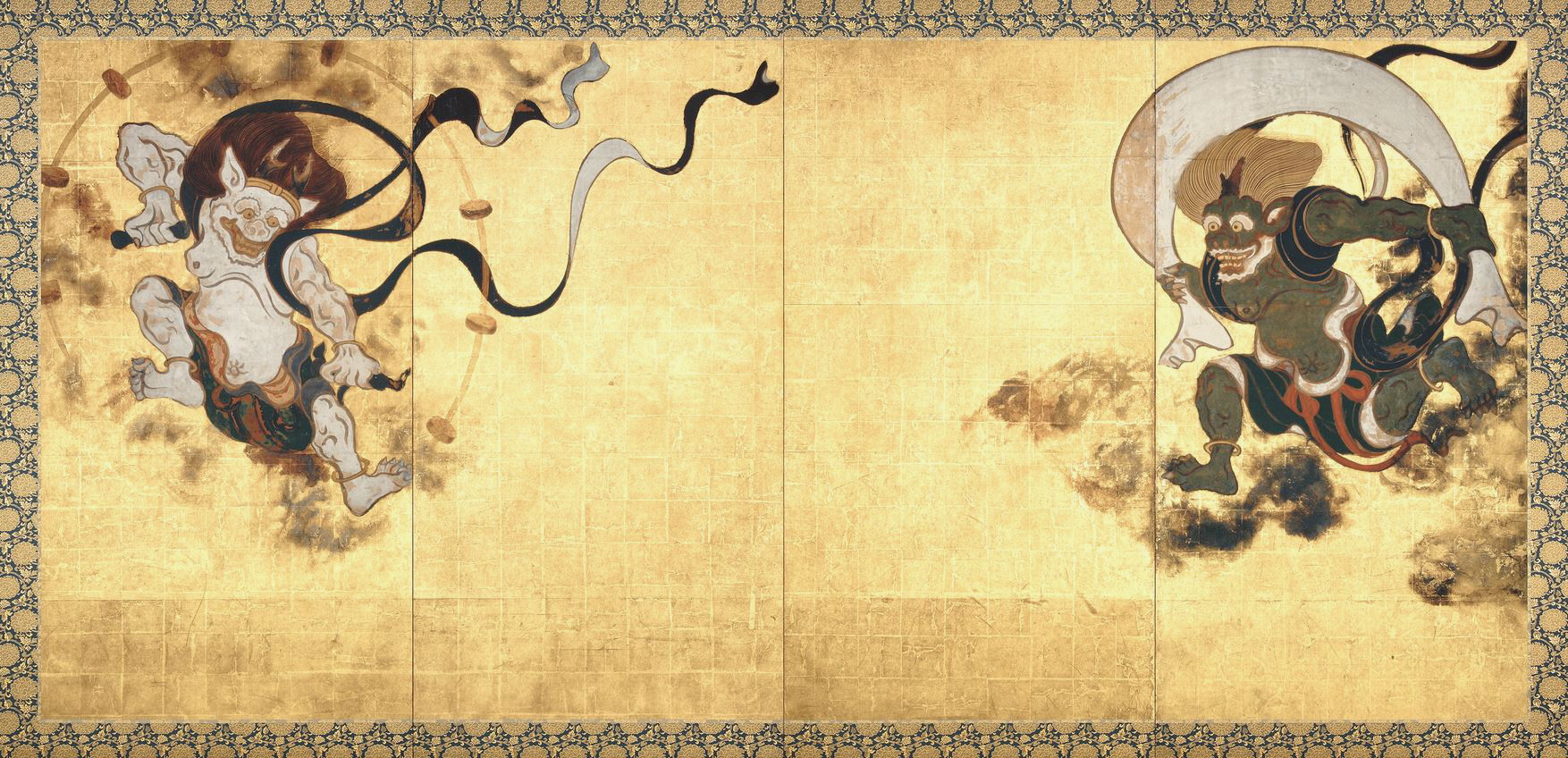

Eventually, after entering his 40s, Koetsu became acquainted with Tawaraya Sotatsu, a young painter who was had talent but had not yet had an opportunity to rise up in the world. In 1602 (at the age of 44) Koetsu was hired to restore the Heike Osamekei, a treasure of the Itsukushima Shrine. He added Sotatsu to his team. It was a grand moment that demonstrated his abilities to the fullest. Sotatsu responded to Koetsu’s great expectations and went on to create masterpiece after masterpiece, such as the Fujin Raijin figure screen. Sotatsu’s talents grew to such an extent that he was awarded the title of Hokkyo, a top-level endorsement by the Imperial Court some 30 years later.

In 1615, after the summer campaign of the siege of Osaka (Osaka natsu no Jin), Koetu’s tea ceremony teacher, Furuta Oribe, was ordered to commit ritual suicide for his connections with the Toyotomi clan. After that, the 57 year old Koetsu’s life came to a major turning point. Tokugawa Ieyasu granted him a 90,000 tsubo (a tsubo equals approx. 3.3 square metre) piece of land in Takagamine in the northwest of Kyoto. According to some theories, Koetsu was banished to the suburbs of the capital due to his involvement with Oribe. In any case, once Koetsu had a place where he could concentrate on art, leaving being the world of power and everyday life, he responded positively to the situation. He tried to attract artists to his new venture and build an artists’ colony that could be considered a utopia. He lived out the rest of his 20 or more years at Takagamine, intensely focused on art.

In response to Koetsu’s call, many metalworkers, ceramicists, makie artists, and painters, together with brush, paper, and textiles businessmen supportive of artistic endeavors gathered together, and Koetsu came to run and direct this “Koetsu-mura” (Koetsu village). Among them was the grandfather of Ogata Korin. Wealthy merchants of elegant taste also came to live there, and the village is said to have had 56 residences. Koetu had a wide circle of friends including samurai, aristocrats, and priests, and even Miyamoto Musashi came to stay at Koetsu-mura before his duel with the Yoshioka clan.

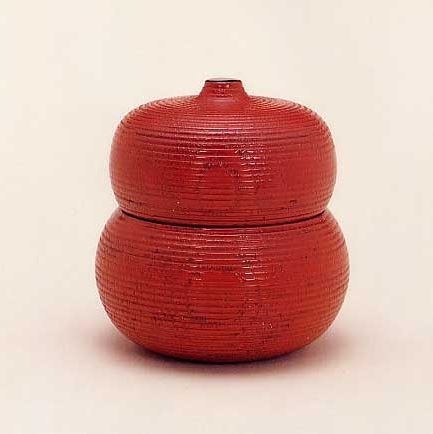

Koetsu was also involved with the tea ceremony, which was hugely popular at this time. Even more than in the past, he focused his energies passionately on ceramics (on the making of tea bowls).

In pottery, Koetsu studied under Raku II (Jokei) and Raku III (Donyu). He did not use a wheel, but instead formed his vessels using just his hands and a spatula. As someone who did not specialize in ceramics and who joined the art from the outside, he developed ideas freely and created tea bowls that are full of individuality. One of Koetsu’s revolutionary acts was to sign his tea bowl boxes with his name. This was the first time in the history of Japanese ceramics that a creator inscribed his name into an item. Until then, even ceramicists did not clearly acknowledge tea bowls as works of art. By signing his name, Koetsu was able to assert the ego of the creator through the tea bowl. At present, there are only two ceramic pieces that are designated national treasures in Japan. One of these is “Fujisan,” which bears Koetsu’s inscription. He named the piece after the view of Mt. Fuji capped in snow. Other masterful tea bowls left to us by Koetsu include “Amagumo (Rain Cloud),” “Seppo (Snow Peaks),” “Shigure (Drizzle),” and “Kaga Koetsu.”

Koetsu and Sotatsu were co-founders of the Rinpa School. Half a century later, the school’s spirit was inherited by Ogata Korin. Koetsu had an immeasurable impact on Japanese culture. He died at 79.

Kobori Enshu

Practitioner of the art of tea ceremony and feudal lord of the Omi-Komuro domain during the early Edo period. He was born in Omi province. From a young age he received special education from his father Shinsuke Masatsugi, took over the main school of tea ceremony continued by Sen no Rikyu and Furuta Oribe, and ascended to the position of tea ceremony instructor for the originators of the Tokugawa dynasty. In year 13 of the Keichou era (1608), he took the role of overseer for the construction of Sunpu Castle, and in doing so, he was bequeathed the official court title of Lord of Totomi, junior fifth-class lower - from this point on, he began to be known as "Enshu".

During his lifetime he conducted over 400 tea ceremonies, at the request of feudal lords, court nobles, vassals, townsfolk - members of all classes - reaching some 2000 people. A master of both calligraphy and waka poetry, he constructed an elegantly graceful and simplistic tea ceremony known as "Kirei-sabi", combining tea ceremony with the ideals of dynastic culture. Beginning with Emperor Mizunoo, he became a figurehead for culture salons during the Kanei era, and demonstrated his talents in the construction and landscape design for Katsura Imperial Villa, Sendougosho, Nijo Castle, and Nagoya Castle, among others. Daitokuji-kohoan and Nanzenji-konchiin are his exemplary works.

In the realm of artistic handicraft, he left a lasting impression in both his selection of "Chuuko-Meibutsu (Revival Goods)" (items chosen based on Enshu's own aesthetic sense) as well as his leadership of the various schools of kuniyaki pottery - Takatori, Tanba, Shigaraki, Iga, and Shitoro. He also concentrated his efforts on importing pottery from China, Korea, and The Netherlands.

Surviving the period of turmoil from Toyotomi to Tokugawa, Enshu, in rebuilding the lineage of Japanese beauty and bringing to fruition an aesthetic focused on the refinement and excitement of the beginning of early modern Japan, created a foundation for reaching an era of peace.

Enshu Nanagama – 7 kilns Enshu likes

Term for the seven pottery workshops all over Japan known for producing unique tea utensils praised by Kobori Enshu. At the time, being found suitable by Enshu's eye was considered the highest honor, and overnight, these workshops took the whole of Japan by storm. Enshu even visited and worked at a few select locations.

Shitoro ware

Shitoro ware refers to pottery produced in Kanaya, Shimada City, Shizuoka Prefecture. It can be traced back to the Muromachi period, beginning with the pottery baked in Mino, and has been long-known as a region ripe with high quality potter's clay. In year 16 of the Tenshou era, a license granted by Tokugawa Ieyasu promoted the region's pottery as a specialty good, and production flourished.

Above all else, the reason for Shitoro ware rising to acclaim was due to the attention received from Kobori Enshu and other practitioners of tea ceremony, as well as its selection as one of the Enshu Nanagama. Even now, they primarily make reddish tea kettles with yellow and black glaze, a much sought-after style. The often-appreciated vessels are exceedingly sturdy and moisture-resistant. The most famous examples are engraved with "Sobokai" and "Uba-futokoro".

Zeze ware

Zeze ware is the term for the pottery of Zeze in Otsu City, Shiga Prefecture. Famous for its tea bowls, it was selected one of the Enshu Nanagama. Praised by Enshuu as an example of "Kirei-sabi" for its characteristic iron glaze with tinges of black, as well as its simplicity and delicate design.

Asahi ware

Asahi ware is the pottery produced in Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture. As the cultivation of Uji-cha blossomed, so did the demand for making tea ceremony utensils. It was selected as one of the Enshu Nanagama during the Edo period.

Remaining anecdotes claim that due to the rise in popularity of tea ceremony in the Momoyama period, founder Okamura Jiroueimon Fujisaku received high praise from The ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi and revised his technique and name - ever since, Asahi ware has been a source of great praise. With the second generation of potters, Kobori Enshu took patronage of Asahi ware, and due to his leadership, its fame only increased further. At the same time, Enshu himself was producing a large number of items at the Asahi ware workshops.

Akahada ware

Akahada ware is the pottery of Nara City and Yamatokoriyama City in Nara Prefecture, a region dotted with ceramic workshops. Although its origin is unclear, it is said that during the Momoyama period, the lord of Yamatokoriyama first built a workshop on Akahada Mountain in the village of Gojo.

Agano ware

Agano ware refers to pottery fired in Tagawagunkawara-machi, Fukuchi-machi, and Oto-machi in Fukuoka Prefecture. At the beginning of the Edo period, when Hosokawa Tadaoki, himself a well-known practitioner of tea ceremony, was appointed lord of the Komura province, he summoned a Korean potter Sokai (Agano Kizou), traveled up to Agano in the Toyosaki province and constructed a workshop - thus began Agano ware. So well-loved by tea ceremony artisans that it was counted as one of the Enshu Nanagama during the Edo period. Agano ware specializes in its variety of enamels used, as well as the natural patterns produced by the glaze melting in the furnace - hardly any decoration is used.

Takatori ware

A historic prefectural workshop with a 400 year history of continued production in Fukuoka City's Sawara District, as well as Nogata City in Fukuoka Prefecture.

Takatori ware was originally fired at the base of Mount Takatori in Fukuoka Prefecture's Nogata City, and because of the Imjin War, Kuroda Nagamasa brought back a Korean potter named Hassan (Japanese name Hachizou Shigesada) who began baking Takatori ware. The workshop is said to have opened in 1600. The kilns at the workshop - Eimanji, Takuma, Uchigaso, and Yamada - are known as "Old Takatori". It prospered as the official kiln for the Kuroda province during the Edo period, and by the Genna era, they summoned a potter from Karatsu and improved their technique. With the arrival of the Kanei era, the second daimyo Kuroda Takayuki increased relations with Kobori Enshu, producing many of Enshu's favorite pieces. By that connection, it was included as one of the Enshu Nanagama, and became well-known as a production center for tea bowls. At present, their focus is on some of Enshu's favorite refined tea bowls fired in the Shirahatasan kiln, known as "Enshu Takatori".

Iga ware

Iga pottery has a long history, and its roots can be traced back roughly 1200 years to the Tenpyo era (729–749), when farmers began to fire the vessels they used while farming.

Owing to its origins near the historical Yamato region, Iga ware has long been at the core of Japanese culture. Historical influence from the Nara court was key to the style's development. Over time, artisans began specializing in pottery, culminating in the late Muromachi period, when Taro Dayu and Jiro Dayu founded the Iga ware style.

Later, in 1584 (Tensho 12), Tsutsui Sadatsugu, under instructions from the lord of Iga, encouraged his friend Furuta Oribe to pursue pottery, and had him produce wares endowed with the fundamental artistic essence of old Iga using the kiln at Ueno Castle.

Among those wares were tea urns, water jugs, tea caddies, and vases, all of which featured stunning and artful indentations. The wares produced during Sadatsugu's tenure (Tensho 13 – Keicho 13) are commonly called "Tsutsui-Iga." In Keicho 13, Todo Takatora became the ruler of Iga, and his son, Takatsugu, became a supporter of Iga ware. The wares produced during this timeframe are called "Todo-Iga". Today, the term "ko-Iga" or "old Iga" refers to both Tsutsui-Iga and Todo-Iga.

During the Kan'ei era (1624–1644), Kobori Enshu crafted teaware and made Enshu-Iga pottery famous.

However, during the reign of the third lord of Iga, Takahisa, obstructions to kaolin mining led to the establishment of the 1669 (Kanbun 9) "Otomeyama" system. As a result, potters departed for Shigaraki, leading to the decline of the Iga ware.