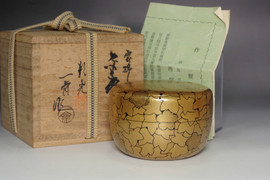

Old Wajima lacquerware tea caddy #5083

- SKU:

- 5083

- Shipping:

- Free Shipping

height: approx. 7.2cm (2 27⁄32in)

width: approx. 7.4cm (2 29⁄32in)

weight: 58g (gross 131g)

writing: Wajima ware, Shozan made

region of Origin: Wajima, Japan

**Wajima Lacquerware (Wajima-nuri)**

Wajima-nuri is lacquerware made in Wajima City, Ishikawa Prefecture. The characteristic feature of Wajima-nuri lies in the use of Wajima ground powder, which is unique to the area. The ground powder from Wajima is made of high-quality clay and is used as a base material, enhancing the durability of the lacquerware. Moreover, the aesthetic appeal of Wajima-nuri is a significant aspect of its charm. The lacquerware is known for its carved decorations filled with gold, and the use of gold and silver powders in a technique called "Maki-e" is particularly renowned. The elegance achieved using gold and silver is visually striking. Wajima-nuri lacquerware, which undergoes more than a hundred steps before completion, is not only durable but also repairable if damaged.

**History**

The origins of Wajima-nuri are unclear, with theories suggesting it was introduced during the Muromachi period by monks from Negoroji Temple, and others stating it was spread by monks fleeing the conflicts of the Sengoku period. Commonly, it is believed to have evolved from daily-use Negoro lacquerware. By the early Edo period around 1630, it had transformed into the form closer to modern Wajima-nuri, with the process largely stabilizing between 1716 and 1736. Before its designation as a national traditional craft in 1975, Wajima-nuri was primarily used for practical items at ceremonial events. Today, it also carries an artistic value.

**Production Process**

1. **Wood Base**

Creating the wood base involves preparing the prototype of items like bowls before lacquer application. Keyaki (Zelkova) and Mizume (Birch) are primarily used, with the wood left to naturally dry for 2-3 years after cutting. After thorough drying, the wood is roughly shaped. Wajima-nuri does not proceed to fine carving immediately; instead, it undergoes a smoke drying process using sawdust, followed by months of natural drying before final shaping.

2. **Undercoat**

The undercoat process unique to Wajima-nuri involves using special ground powders. First, slight carvings are made to prevent damage from cracks, which are then covered with an undercoat for reinforcement. "Kisemono-zuri" involves reinforcing vulnerable areas with cloth. The undercoat is meticulously applied, focusing on areas prone to damage, creating a robust foundation. The entire piece is then coated with a mixture of raw lacquer and polishing powder.

3. **Top Coat**

The top coat is applied evenly over the undercoat. The lacquer used is processed alongside earlier steps, beginning with collecting it from trees between June and October. Only about 200g of lacquer can be collected from a single tree per day. After collection, the lacquer is filtered and purified. Wajima-nuri uses refined lacquer, which is treated to prevent fading, ensuring longevity. The top coat is applied in a dust-free environment at optimal temperature and humidity.

4. **Decoration**

After the top coat, the lacquerware is polished to a shine in a process called "Roiro". Delicate sanding materials are used to avoid scratches. Decorations such as Maki-e and inlaid gold or silver are then applied, enhancing the beauty of Wajima-nuri lacquerware.

Natsume is a traditional tea caddy made from high-grade wood and decorated with a gold lacquer called Makie. Its name comes from its shape, which is like a jujube (natsume in Japanese). Before the famous artist Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) used natsume tea caddies in his tea ceremonies, pottery tea caddies were the norm. Natsume was used for daily necessities as pill case or something for townsman. Natsume remains popular with Tea Ceremony masters to the present day.

Originally, usucha (weak green tea) was called "packed tea" because it was a low-quality tea that was used to fill in the space around bagged koicha (strong green tea) when it was placed in a tea earn. For that reason, from the time of Takeno Joo to the time of Sen no Rikyu, "tea" only referred to koicha. Because usucha was looked down upon, its container was a wooden box called a hikiya, the purpose of which was to store the chaire, koicha tea caddy. In other words, the case originally used for the chaire, koicha tea caddy, was put to another use, eventually being used independently as a usucha tea caddy. Technically, the hikiya for tea containers like nasu (an eggplant-shaped tea caddy) and bunrin (an apple-shaped tea caddy) is called a natsume and the hikiya for katatsuki (a container with protruding parts at the top) is called a nakatsugi, but generally, it is common to refer to both kinds of hikiya as natsume. They are broadly classified as large natsume, medium natsume, and small natsume, and each of these categories is further divided into large, medium, and small.