Types of Japanese Pottery and Porcelain

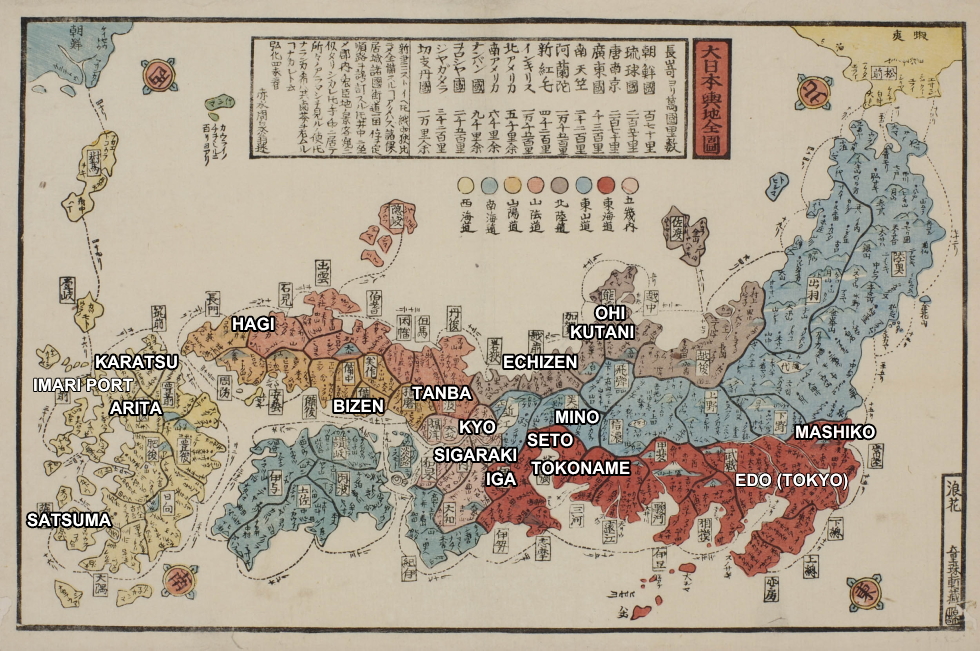

Agano / Akahada / Arita (Imari) / Asahi / Banko / Bizen / Echizen / Hagi / Inuyama / Iga / Izushi / Karatsu / Kutani / Kyo / Mashiko / Mino / Mumyoi / Ofukai / Ohi / Raku / Sanda / Satsuma / Seto / Shigaraki / Shino / Shitoro / Soma / Takatori / Tamba / Tokoname / Tsuboya / Zeze

Agano ware

Agano ware refers to pottery fired in Tagawagunkawara-machi, Fukuchi-machi, and Oto-machi in Fukuoka Prefecture. At the beginning of the Edo period, when Hosokawa Tadaoki, himself a well-known practitioner of tea ceremony, was appointed lord of the Komura province, he summoned a Korean potter Sokai (Agano Kizou), traveled up to Agano in the Toyosaki province and constructed a workshop - thus began Agano ware. So well-loved by tea ceremony artisans that it was counted as one of the Enshu Nanagama during the Edo period. Agano ware specializes in its variety of enamels used, as well as the natural patterns produced by the glaze melting in the furnace - hardly any decoration is used.

|

Hosokawa Tadaoki |

Akahada ware

Akahada ware is the pottery of Nara City and Yamatokoriyama City in Nara Prefecture, a region dotted with ceramic workshops. Although its origin is unclear, it is said that during the Momoyama period, the lord of Yamatokoriyama, Toyotomi Hidenaga, first built a workshop on Akahada Mountain in the village of Gojo.

In the later Edo period, a potter Okuda Mokuhaku painted Nara-e on akahada ware and its became very popular among tea ceremony masters.

The kiln was counted as one of the Enshu Nanagama.

Nara-e

Picture book illustrations with colored brushstrokes, themed around old stories (mainly fairy tales), Noh songs and so on, created from the Muromachi period up to the middle of the Edo period.

|

Toyotomi Hidenaga |

|

Asahi ware

Asahi ware is the pottery produced in Uji City, Kyoto Prefecture. As the cultivation of Uji-cha blossomed, so did the demand for making tea ceremony utensils. It was selected as one of the Enshu Nanagama during the Edo period.

Remaining anecdotes claim that due to the rise in popularity of tea ceremony in the Momoyama period, founder Okamura Jiroueimon Fujisaku received high praise from The ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi and revised his technique and name - ever since, Asahi ware has been a source of great praise. With the second generation of potters, Kobori Enshu took patronage of Asahi ware, and due to his leadership, its fame only increased further. At the same time, Enshu himself was producing a large number of items at the Asahi ware workshops.

Arita ware (Imari)

Old Imari is quite probably the most famous Japanese ceramic product in the world. China, the dominant exporter of porcelain, fell into internal disturbances in 1644 and it became hard to obtain Chinese products. The west requested Japan to step up production of porcelain instead of China because Europe did not have the techniques to make porcelain at that time. Thus substantial amounts of Japanese porcelain ware were made in the town of Arita and exported to Europe from the port of Imari by the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) from the late 17th to early 18th century in order to meet demand in the west. Thus Arita porcelain is also often known as Imari. Arita ware was the first porcelain product in Japanese history, and strongly influenced European ceramics.

Sakaida Kakiemon

Kakiemon ware is a kind of Arita ware. Sakaida Kakiemon (1596-1666) was the founder of the famous Kakiemon kiln. His work featured very well-shaped porcelain with colorful painting, a well-balanced margin in a beautiful ivory white glaze, and Kuchisabi, a printed iron glaze on the top of the rim. His porcelain strongly influenced European ceramic companies such as Meissen, Herend and Royal Crown Derby among the others. In particular their plates and cups & saucers were influenced by Japanese porcelain at the time. Today, the 14th successor to the Sakaida Kakiemon kiln continues the excellent work.

Meissen Kakiemon cup & saucer and Royal Crown Derby Old Imari plate

Age of Old Imari

It is very difficult to distinguish the age of porcelain products. Experts and amateurs alike use knowledge about the historical features of Imari ware in different eras to identify genuine antiques and avoid fakes.

Kakiemon White

Sakaida kakiemon succeeded in making an original white glaze called Nigoshide c. 1650-1670. However his earlier white glaze was not as skilled. He was unable to use cobalt blue under the white glaze because the blue changed to almost black after firing due to the iron content of the glaze being oxidized. He therefore had to paint blue parts of the picture over the white glaze. Thus old Imari with beautiful cobalt blue painting under an ivory white glaze is not eary Imari.

Kinran-de

From 1690, the Kinrande style emerged. It became popular and soon took the place of Kakiemon style. Kinrade ware was exported to Europe by the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC). That had cobalt blue paint under the white glaze and colorful paint including gold over the glaze. Around the time a new color, yellowish green was developed. Kinrande also influenced European ceramics. In the present day, old Imari usually indicates Kinrande ware in Europe. It is the origin of the famous Royal Crown Derby old Imari series.

Some-Nishiki

This is mixed style between Some-tsuke style and Nishiki-de style. Some-tsuke style had just cobalt blue paint under the white glaze. Nisiki-de style had red, green, yellow, purple, blue paint over the white glaze.

Some-Nishiki had cobalt blue paint under the white glaze and colorful paint over the glaze. It is looks like Kinran-de however it is less flashy than Kinran-de due to hardly gold glaze. Some time they were called Jo-de (excellent porcelain) as tributes for the ruler.

Plate Size

Saya (sagger) is a box made of clay to protect the porcelain in the kiln. Using this tool, a potter could make a well shaped product. Saya were around 30cm across at most. Therefore many early well-shaped Imari products were about 20cm across. The potter could not use the Saya when they made a bigger plate. Therefore perfectly shaped imari over 30cm are not so old.

Arabesque Pattern

Many Imari ware have arabesque designs. Early arabesques were drawn delicately. However overtime, the style became rougher. In the mid Edo era, the pattern resembled octopus legs It is called Tako-Karakusa . In the late Edo era, the pattern, called Shida-Karakusa, became almost like ferns.

Tako-Krasakusa and Shida Karakusa

Signature - Back Sign

Nomally reproductions have a signature like that on the picture on the top in order to distinguish antiques from reproductions. The other pictures are the signatures of antiques. They are many types of signatures, these are just four examples.

|

|

The mark is called 'Uzufuku' means fortune. |

|

It is Chinese name of an era. |

|

|

Fuki-Choshun means happy. |

|

This is mark of the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie. |

Olive Green

In the late edo period, enamel coating technique was imported from China. Painting , gradation and overglaze technique in particular, became more skilled. If you see 'Uguisu-iro (olive green)', lower left side of the picture, on your imari plate, it was made after late 18c because no one was able to make 'uguisu' color painting without enamel coating tequnique at that time.

Banko Ware

About 260 years ago, in the middle of the Edo era, there lived a wealthy merchant by the name of Nunami Rozan. Rozan, having a deep knowledge of traditional tea ceremony, had an interest in the art of ceramics. With a desire to let his creations be handed down and used eternally, his ceramics were stamped with the words "Banko Fueki", meaning “constant eternity,” and from that the name banko ware was born. The craft of such banko ware ceased with the passing away of Rozan. However, during the later stages of the Edo period, the fire crafting of banko ware was rekindled.

The crafting of Yokkaichi Banko Ware of present day is based on creations made at the beginning of the Meiji era, after exhaustively researching the creation techniques of that period.

From 80% to nearly 90% of such clay ware are found within Japan. A distinction of banko ware cooking pots is in the clay that they are made of. It has exceptionally good thermal resistance and demonstrates high durability even when used on direct flames of a gas stove or charcoal fire, or even when heated empty.

Teapots, just like clay cooking pots, are among the exemplary creations of banko ware. The teapots are made using red clay which is sourced from the local land and contains iron, and they acquire a purple tone after undergoing reduction firing for an extensive period of time. As the teapots are used, their sheen becomes ever further glossy, and by absorbing away the tartness the pots have a mellowing effect on the taste of tea.

Bizen ware

Bizen ware is Japan's oldest pottery-making technique, introduced during the Heian period (794-1192). It is a type of pottery identifiable by its iron-like hardness, reddish brown color, absence of glaze, and markings resulting from its wood-burning kiln firing. The surface of Bizen ware is entirely dependent on yohen (discoloration of the ceramic by the kiln). Characteristic features include Hidasuki, a red and brown fire-cord decoration created by rice straw wrapped around pieces, and Enokihada, a hackberry glaze spotting produces by pine ash.

Bizen Ware Clay

I sometimes go to ceramics manufacturers to learn about ceramics. While most pottery you see is used for tea, a lot of Bizen ware is used for sake and boiled food. While this is occasionally difficult for somebody like myself who does not drink, it speaks of how Bizen ware goes well with Japanese alcohol and cooking.

The material used to make Bizen ware comes from a layer of clay called "hiyose" found in the vicinity of Imbe. It can only be collected in a few specific areas, and back in the Momoyama period most of the clay was collected from rice fields.

Dirt in rice fields is insulated from the air, and it is a breeding ground for organic matter, turning it into a viscous clay.

Rice fields are kept topped off with water from the spring planting until the fall harvest, and the dirt in these fields undergoes a continual, natural separation process, resulting in a viscous clay. In addition, when the fields are harvested the water is drained, and the sun shines upon the ground. This causes the water preferring microbes and water adverse microbes to reciprocally multiply, leading to the formation of good soil, which becomes exceptionally viscous clay that is good for pottery.

Due to this process, a single spoonful of the clay contains over one hundred million microbes, and putting the clay in storage to rest allows 80 varieties of yeast to grow.

A majority of these are antibiotics known as penicillin, and longtime Bizen ware potters often say, "If you get injured rub some clay on it."

Hiyose is very viscous and has a low resistance to fire, and compared to other types of pottery clay it contains a lot of iron. Because Bizen ware does not use glaze, potters are extremely sensitive to the composition of the clay. Ensuring a high quality clay is of top importance to the artist.

A piece of Bizen ware created from carefully processed clay, even if it does not appear spectacular when first purchased, after years of continued use will transform into a fine piece that hardly resembles the original.

Bizen Ware Background

1 "Sangiri"

Sangiri and Kumadori (kabuki shading)

During firing, a portion of the piece is buried in ash or soot, and due to reduction firing via restricted airflow, the portions that the flame touches turn reddish brown, while the portions covered in ash turn black or gray.

The line between these regions looks almost like a frame and is called "kumadori" (shading), and in the finest pieces there are whites layered on top of yellows, with more yellows layered on top of that.

Because they are fired in the part of the kiln closest to the flame, damage and deformations are common, and only a very small quantity can be fired at a single time.

Originally the inside of the furnace was partitioned by a san (crosspiece), and the pattern arose below the san, leading to the term sangiri.

There is also the separate method of "sumisangiri," said to be discovered by Kaneshige Toyo. With this method sumi (charcoal) is added later to artificially give the appearance of sangiri to pieces that did not change much during firing, and this method is commonly used today. However, when compared to natural sangiri these pieces give off a different feeling, and the two methods are distinct from one another.

2 "Haikaburi" (ash covered)

During firing pieces are buried in wood ash or soot, which dissolves and chars from the process. This is another reason why, with the firing done in the part of the kiln closest to the flame, damage and deformations are common, and only a very small quantity can be fired at a single time.

3 "Goma"

The wood ash falls naturally, and due to the high temperatures as it melts it gives the appearance of a glaze. It looks as though goma (sesame seeds) have been sprinkled on the piece, so this is called goma. There are various colors, including whites, yellows, and greens. As the goma melts, it becomes a substance that looks like a flowing glassy glaze, which is called "tamadare" (egg dripping).

4 "Kasegoma"

One variety of goma comes when ash that has been stripped of its moisture from the heat clings to the piece, and as it melts it gives the appearance of ash color, rough and dry skin. The feeling of wabi (aesthetic emphasizing simplicity) given off by such pieces has been particularly prized in tea ceremonies since ancient times.

5 "Hidasuki"

Kaneshige Toyo's younger brother Sozan created this form of firing, and he himself said, "My older brother (Toyo) left this for me."

Firing is done without direct contact from the flame, and the parts that are wrapped in straw have a reaction with the iron in the clay and the alkali in the straw, causing a red coloring. On the white background the vivid red left behind by the straw looks like a sash, so it is called "hidasuki" (red sash).

6 "Botamochi"

Originally, because space in the kiln was limited, pieces were piled up when fired. The spaces where they touched were discolored, and those parts did not match the style of the rest of the piece. Nowadays, highly fire resistant cracker shaped discs called "bota" are often placed on pieces when firing to intentionally create botamochi patterns.

7 "Aobizen"

Bizen ware is normally fired using an oxidized flame, but sometimes due to the conditions of the pieces in the kiln or other factors there is reduction, and this can cause the entire piece to have a blue tint. This is called aobizen (blue Bizen), and among the many types of variations it is among the rarest and quite highly valued.

There is also a separate method where salt is added, which causes alkali to coil around the surface, and via reductive cooling this can also give a blue tint. This method is distinct from aobizen, and it is called "shioao" (salt blue) or "shokuenao" (table salt blue).

8 "Kurobizen" (black Bizen)

Coating a shaped piece with clay that causes black coloration or using clay that will become black when fired is called "imbede" (Imbe method). This coating technique can often be seen in pieces of ancient Bizen ware dating back to the Edo period.

9 "Ishihaze" (stone popping)

During drying or firing the shrinking of the clay can cause stones on the inside to rise to the surface, and this is also called ishikami. Sometimes this can cause a leak in a piece. This gives the appearance of the stone popping out of the piece, and it is very highly valued as it presents a good scene.

The charm of Bizen ware

1. It doesn't break even when thrown

Bizen ware is fired without glazing at a temperature of over 1200 degrees for approximately two weeks, giving it a higher level of strength than other pottery. That is why, along with Arita ware, it has long been known as pottery which "Doesn't break even when thrown...."

2. Cold beer, warm tea

As Bizen ware has an elaborate internal structure, it has a high specific heat capacity. Because of this, it has strong heat-retention properties, and is difficult to heat and to cool.

3. Delicious beer with delicate foam

As Bizen ware has minute irregularities and high foaming abilities, and the foam is delicate and long-lasting, it retains the flavor, allowing it to be enjoyed even more.

4. If you leave it for a long time, it improves the flavor of sake

Bizen ware contains minute interior pores, which cause a certain extent of subtle permeability. Due to this, the aroma of sake, whiskey, and wine increases and mellows, promoting a rich flavor transformation.

5. It delivers delicious dishes

Bizen ware has more small irregularities on the surface compared with other pottery, so food doesn't stick to the dishes and is easy to remove, and it has weak moisture evaporation properties, which prevents food drying out.

6. Fowers in vases last longer

Bizen ware has minute pores and a certain extent of permeability, so it maintains the condition of fresh water for a long time, making flowers last longer.

7. It takes on a smooth texture with use

By breaking Bizen ware in, the edges of the fine irregularities on the surface are gradually removed, and its quiet charm increases the more it is used.

Echizen ware

Echizen, home to one of the six old pottery styles of Japan, was originally a site where Sue wares were manufactured. However, in the late Heian period, following the adoption of technology from Tokoname, Echizen started to produce pottery. Though Echizen pottery at the time was unglazed, the highly-vitreous nature of Echizen's soil ensured that the wares did not leak. In addition, ash from the wood fuel would fuse with the exterior surface of the wares, producing beautiful green patterns.

By the late Muromachi period, an enormous kiln, over 25 meters across, had been built in the town of Echizen, allowing for the mass production of wares. Up to five tons of wares, the equivalent of 60 pots or 1200 mortars, could be fired at once. This completed the transformation of Echizen into a major pottery site, consuming huge amounts of clay and wood, and serving as home to a large number of potters.

The hard, sturdy pottery built in the hills of Echizen was shipped all along the Sea of Japan, from southern Hokkaido in the north to Shimane prefecture in the south. Echizen pots and vases were prized for their ability to store reserves of water and grains; indigo dye; and coinage metals. By the late Muromachi period, Echizen had reached its peak, becoming the largest site of pottery manufacture in the Hokuriku region, and, indeed, the largest site along the western coast of Japan.

However, by the middle of the Edo period, the rise of the Seto ware led to the waning of the Echizen ware, with a concomitant decrease in the amount of wares produced.

Hagi ware

Hagi ware emerged over 400 years ago. It is a type of Japanese pottery very identifiable for its mixed clay made with three type soils (Daido soil, Mitake soil and Mishima soil) and the use of a feldspar glaze. It originated after the Imjin War (1592-1597) with the ‘Lee Brothers’ potters from Korea. A feature of the clay is that it is comparatively soft and absorbent. Hagi tea bowls are perfect for green tea. The more often you use them, the greater their charm, as the surface develops a patina from properties in the tea penetrating the inside of the bowl over time.

During the Edo period, the Hagi ware pottery was under clan protection, but with the upheaval of the Meiji Restoration it lost its support and faced hardship, and the majority of it disappeared along with the Westernization of Japan. However, Miwa Kyusetsu established the unique "Kyusetsujiro (Kyusetsu-white)" style, and in addition, the twelfth generation Sakakura Shinbei spread Hagi ware throughout the country, which saved it from decline.

The charm of Hagi ware - The seven disguises of Hagi

Known as bowls loved by masters of the tea ceremony since long ago, so much so that they are celebrated in "Raku first, Hagi second, Karatsu third," they enjoy firmly-rooted popularity.

However, it is not unusual to hear stories such as "When I poured some tea into the bowl I bought at Hagi the other day, it soaked through to the outside of the bowl. I wonder if it's a defective item." That's because in fact, when you first start using Hagi ware, it sometimes leaks.

However, this leaking is actually the biggest feature of Hagi ware. The soft-textured soil of Hagi ware is coarse and has a lot of tiny gaps. Furthermore, moisture permeates into the bowl through fine cracks called "intrusions" which occur on the surface of the bowl due to the difference in shrinkage ratios between the soil and the glaze, and may even come out onto the surface.

By repeatedly pouring tea into a teacup which was leaking at first, the coarse soil gradually becomes clogged by tea stains, and stops leaking. Thus, by using Hagi ware for many years, the likes of the ingredients in the tea soak into the intrusions, and the texture changes. This phenomenon is called "The seven disguises of Hagi," and it is a main feature which makes Hagi ware highly valued as bowls for the tea ceremony among those who like elegant simplicity.

Due to these circumstances, there are many simple Hagi ware pieces, and almost none are decorated with the likes of painting.

Inuyama ware

Inuyama ware originated during the Horeki era (1751-1763) in Imaimiyagabora, when pottery stamped with the kiln mark "Inuyama" was produced.

It was developed on the commission of the Inuyama clan in the 19th century. The Inuyama style, a Gosu red painting design of the Lord of Inuyama Castle, Naruse Masanaga, is patterned after Chinese Ming Dynasty Gosu red painting and many tea articles are made using the characteristic cloud brocade pattern, which includes Korin-style cherry blossoms and maple leaves.

During the long history of Inuyama ware, the kiln has faced closure many times, but craftsmen ranked alongside Kyoto's Okuda Eisen, such as Dohei and Ozeki Sakujuro Nobunari, have worked hard to revive it.

Iga ware

Iga pottery has a long history, and its roots can be traced back roughly 1200 years to the Tenpyo era (729–749), when farmers began to fire the vessels they used while farming.

Owing to its origins near the historical Yamato region, Iga ware has long been at the core of Japanese culture. Historical influence from the Nara court was key to the style's development. Over time, artisans began specializing in pottery, culminating in the late Muromachi period, when Taro Dayu and Jiro Dayu founded the Iga ware style.

Later, in 1584 (Tensho 12), Tsutsui Sadatsugu, under instructions from the lord of Iga, encouraged his friend Furuta Oribe to pursue pottery, and had him produce wares endowed with the fundamental artistic essence of old Iga using the kiln at Ueno Castle.

Among those wares were tea urns, water jugs, tea caddies, and vases, all of which featured stunning and artful indentations. The wares produced during Sadatsugu's tenure (Tensho 13 – Keicho 13) are commonly called "Tsutsui-Iga." In Keicho 13, Todo Takatora became the ruler of Iga, and his son, Takatsugu, became a supporter of Iga ware. The wares produced during this timeframe are called "Todo-Iga". Today, the term "ko-Iga" or "old Iga" refers to both Tsutsui-Iga and Todo-Iga.

During the Kan'ei era (1624–1644), Kobori Enshu crafted teaware and made Enshu-Iga pottery famous.

However, during the reign of the third lord of Iga, Takahisa, obstructions to kaolin mining led to the establishment of the 1669 (Kanbun 9) "Otomeyama" system. As a result, potters departed for Shigaraki, leading to the decline of the Iga ware.

Izushi ware

Izushi ware is white porcelain. The ware is synonymous with a porcelain surface which is said to be a "white that is too white,” and the porcelain engraving that takes advantage of this. Izushi ware has been designated a traditional craft of Japan.

Izushi kiln had been a kiln for pottery wares, but in 1789, Chinzaemon Nihachiya struck on the idea of firing porcelain. He borrowed money from Izushi Domain and spent several weeks in Arita learning porcelain production before returning to Izushi with potters from Arita.

He then attempted to start porcelain production, but met with little success due to lack of finances.

In 1799, the Izushi Domain decided to take over direct management of the kiln. Around this time, high quality pottery stone was discovered in Kakitani and Taniyama. With this, the domain relocated the kiln to Taniyama and seized the opportunity to start porcelain production at the domain kiln. The wares produced at the kiln at this time were high-quality blue and white wares in the vein of Imari ware and white porcelain pieces. Ceramics production at Izushi finally took off during the Tempo era of the Edo period (1830–44). However, the kiln was not managed well and ended up being consigned by the domain to private management.

Finally, with the appearance of the company Eishinsha, the roots were laid for the “white that is too white” porcelain that we know today. The company was established in the early years of the Meiji period in 1876. It brought together potters who had lost work with the abolition of domains and establishment of prefectures that took place during bakumatsu times and went on to improve Izushi ware. As a result, a cool, clear and sophisticated white porcelain came into being. These porcelain wares were displayed at the Exposition Universelle of 1889 in Paris and were highly acclaimed, making the name “Izushi ware” famous throughout the country. In 1904, Izushi ware went on to be awarded gold medal in the St. Louis World's Fair.

Unfortunately, Eishinsha was dissolved in 1885, but the heritage that the company left behind was significant, and potters continued to develop the white porcelain of Izushi ware.

Karatsu ware

Karatsu chawan (tea bowl) is very popular, as person of refined taste said: "First Ido, Second Raku, and Third Karatsu". Among other things, Karatsu tea bowls have unique features and atmosphere. The origin of Karatsu ware was Korean pottery actually. The potters were brought from Korea opened kilns and made Korean style pottery after Imjin War (1592-1597), Japanese Toyotomi Hideyoshi troops invaded Korea. While the story of its origin is a shameful episode in Japanese history, excellent Korean pottery techniques were handed down to Japan. Therefore the drawings on early karatsu ware are in the Korean style, while later drawings are more Japanese. Mikaduki-koudai (crescent shape foot) and Zarame (red rough clay) are some of the special features of karatsu chawan.

Karatsu clay is hard. It is appeared the shrunk ‘chirimen-jiwa’ when shave the bottom of karatsu ware with bamboo spatula.

The uniqueness of Karatsu ware—or Karatsu Yaki—lies in its glaze and clay. The glaze most commonly used in Karatsu ware is the soil ash glaze. It comes from wood ash and is the most widespread basic glaze of Karatsu ware. The second most commonly used glaze—the straw ash glaze—uses the cloudy characteristic of straw ash to bake the Karatsu ware and give it a cloudy tint. Other glazes such as iron glaze, ash glaze etc., are also used.

While there are many types of clay used to make Karatsu ware, the most commonly used is one known as Suname in Japanese—"Suna" means sand and "me" means appearance—due to the characteristic roughness of this clay. The second most commonly-used clay is called fine Suname; it is strongly adhesive. Fine Suname clay has parts that are highly rich in iron and other parts that are not. The former turns blackish brown after the firing process. As the latter becomes near-white upon firing, motifs brushed onto this part of the clay develop a vivid color.

Oku-Gorai

This is a style of pottery fired in Kanatsu that emulates Korean tea bowls such as Ido, Komagai, Goki, and Kaki no Heta (Persimmon Calyx).

In the wabi-cha style of tea ceremony during the Momoyama Period, Korai tea bowls such as the rustic Ido tea bowl came to be highly valued. It is believed that the Oku-Gorai tea bowls imitated the Korai style of pottery and were made for use as Matcha (a special type of green tea that is finely grounded) bowls. It is plain, rustic, and does not come with iron pigment brushwork. A feldspar glaze is applied over it save the foot of the tea bowl. The glaze of Oku-Gorai tea bowls have a hue that ranges from loquat to white to orange or brown similar to those of Korai tea bowls. By adjusting the flames, a reddish or bluish glaze may also be produced. In the same way the tea ceremony saying "First Ido, second Raku, third Karatsu" was used to rank tea ware, Oku-Gorai tea bowls have been treasured by since tea masters in the past as the representative style of Karatsu ware.

E (Brush decorated) Karatsu

Various motifs such as grass, trees, flowers and birds are brushed onto an unfired piece using Oni'ita (a slip made from a type of limonite mined everywhere). The piece is then given a feldspare or wood ash glaze. It can be said to be another representative style of Karatsu ware. The hue of the glaze depends on the iron content of the clay. For clay that is low in iron content, the glaze turns loquat in an oxidizing flame, and whitish to grayish in a reducing flame.

Chosen (Korean) Karatsu

Words where two kinds of glazes are applied over the ware—cloudy straw glaze and amber glaze (a kind of iron glaze)—whilst allowing the second layer to run over the first are known as Chosen Karatsu. The cloudy straw glaze and amber glaze weave into each other and giving rise to a exquisite flowing pattern, making works with the Chosen Karatsu style aesthetic as a decorative pieces.

Madara (Mottled) Karatsu

Pottery coated with the white glaze of rice straw ash are known as Madara Karatsu. The straw ash glaze is prone to producing mottles on fired clay. It is said that the Madara Karatsu earned its name from the bluish spots originating from the ashes of wood such as pine—used as fuel for the kiln—when it stuck to the surface of the clay during firing.

Seto Karatsu

The technique of baking clay of low iron content coated with a feldspar glaze is divided into that of Kawakujirate (lit. Whale skin's color) and Seto Karatsu. The rim of Kawakujirate tea bowl is outlined in black by an underglaze brush with iron pigment. It is known as Kawakujirate because its final hue resembles the color of whale skin. A glaze color ranging from loquat to gray can be seen in flat tea bowls. Seto Karatsu has features which imitate those of Korei tea bowls and there are also deep and shallow tea bowls similar to those of Komagai and Goki styles. The glaze color ranges from white to loquat to gray, and its white glazes turn out same as those of Shino ware.

Mishima (Stamp/Slip Inlay) Karatsu

The style of Mishima Karatsu pottery is said to have descended from South Korean potters who took reference to the Mishima ware that were being made in the Korean peninsula at that time. Motifs such as floral patterns, lines, clouds and cranes are carved onto leather-hard ware, which is then coated by a layer of white slip. The white slip is then wiped or scraped off, and a feldspar or wood ash glaze is applied.

Kutani ware

The history of Kutan ware goes back to around 1655 (first year of Meireki Era), early years of Edo Period.

Maeda Toshiharu, the first feudal lord of Daishoji domain which was a branch domain of Kaga, focused on the fact that magnetite was found at a gold mine in his territory of Kutani (present-day Kutani, Yamanaka-machi, Ishikawa-prefecture), and he ordered Goto Saijiro, who officiated as a person in charge of gold refining at the mine, to learn about porcelain manufacturing at Arita in Hizen.

The Kutani ware is said to have begun at the time of building a kiln in Kutani through the introduction of the technology.

The kilns in Kutani were suddenly closed about 1730 (15th year of Kyoho Era), but the cause of it is still unknown.

Porcelains made during this period are presently called Kokutani (old Kutani), and as a typical Japanese porcelain decorated with colored pictures, their unique and strong beauty of the style is highly evaluated.

Kyo ware

Kyo ware is the generic name for ceramics made in Kyoto. Common types include Raku ware, Kiyomizu ware, Otowa ware, Omuro ware and Rengetsu ware among others. In the eary Edo priod, famous potter Nonomura Ninse appeared. His pottery influenced Japanese culture. It was colorful, and considerably different from previous rustic and natural-looking pottery. There were many great Kyo ware potters including Ogata Kenzan, Okuda Eisen, Aoki Mokube, Kiyomizu Rokube, Ninnami Dohochi and Eiraku Hozen. Many of their products are exhibited in art museums around the world.

Otagaki Rengetsu

Otagaki Rengetsu (1791-1875) was a Buddhist nun who is widely regarded as one of the greatest Japanese poets of the 19th century. She was adopted at a young age by the Otagaki family. It is said that she didn’t live a happy life because she lost her adoptive father and five brothers from illness. She married, but her husband died soon after. She remarried but lost this husband too from illness after only four years, as well as her young son and three young daughters. She joined the temple Chion-in and became a nun, taking Rengetsu ("Lotus Moon") as her Buddhist name. She made pottery inscribed with her poems with a spike in order to make a living. Fortunately her products became popular and she became very wealthy. However she continued to live a simple life. She donated a large amount of money during a famine in the 1850’s and devoted herself to saving the poor late in life.

Raku ware

Raku ware is a type of pottery that is traditionally and primarily used in the Japanese tea ceremony, most often in the form of tea bowls called Raku chawan. In the Momoyama era (1568-1603), the first raku chawan was made by famous artist Raku Chojiro, the founder of Raku ware, after receiving orders from Sen no Rikyu, Japan's most famous Tea Ceremony artist. Rikyu also served ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In the late Momoyama era, Rikyu ordered Raku Chojiro to make kuro raku chawan. Kuro means black in Japanese. Hideyoshi disliked black, and Rikyu ordered the black bowls knowing this. It is also said that Rikyu did this because Hideyoshi was considering invading Korea at that time. Sen no rikyu was against Hideyoshi actually. Unfortunately Hideyoshi ordered Rikyu to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) for another reason. After he died, his philosophy, "wabi" lived on with the black Raku bowls. Raku ware became one of the famous Tea Ceremony bowl styles to the present day. Wabi means accepting imperfection. This is a beautiful Japanese philosophy.

Raku ware is a type of pottery that is usually made without a wheel, formed only with the hands and a spatula according to a method called "hand kneading," then fired at 750℃- 1,100℃ and softly glazed.

In reflection of the aesthetics of Sen no Rikyu and his contemporaries, its characteristics include slight distortions from hand-kneading and a thick form. They are used as tea ceremony tools, such as chawan (tea bowls), hanaire (vases), and mizusahi (lidded water pots).

Kuro-raku

Kuro means black. Initially, a bisque is made, then painted with an iron glaze made from black stones from the Kamogawa River, dried, then, after repeating the glazing process a dozen times, it is fired at 1,000℃. While the glaze melts during firing, the piece is pulled rapidly from the kiln at the moment decided by the artisan, blackening it. This technique was common among the Mino.

It began with Chojiro, firing the first Kuro-raku chawan around 1581- 1586.

Aka-raku

Aka means red. Red clay is fired into a bisque, then a transparent glaze is applied and the piece is fired at 800℃. Aka-raku is famous for Honami Koetsu, a man deeply involved with the Raku family, and the pieces that introduced the way of Raku. In Rikyu's episode, it is said that Hideyoshi disliked Kuro-raku, preferring Aka-raku.

Also, the Raku family has some characteristic firing techniques which were transmitted from generation to generation. Many of the techniques were invented by Donyu.

So, let me tell you about the techniques here.

Jakatsu-gusuri (snake's scale glaze)

It is usually a line of white glaze running down the edge of the black glaze. This glaze usually appears filamentous while the line is made to look fuzzy like a dispersion pattern, sometimes resembling a wave in the sea, however, this does vary between generations. It was invented by the 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu.

Maku-gusuri (curtain glaze)

Maku-gusuri (curtain glaze) is applied after the initial glaze, making it appear like there is a “curtain” over the bowl’s initial glaze. First, the bowl is glazed, then another glaze is applied over it, and finally, the bowl is put into a kiln where the firing makes the top glaze melt, creating a curtain like shape over the initial glaze. It was invented by the 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu.

Shu-gusuri (vermilion glaze)

Shu-gusuri (vermilion glaze) is made by adding a copper‐base to the black glaze, making the bowl have a mottled black and red (vermilion) pattern.

Kihage-gusuri (yellow glaze)

Kihage-gusuri is a yellow glaze which includes very small amounts of iron content. ‘Ki-hage’ means that the yellow glaze appears like paint peeling off of the black glaze. The 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu, began using the technique first and after, the 11th generation Raku family descendant, Raku Keinyu, and the 12th generation, Raku Konyu, used the technique many times.

Ame-gusuri (amber glaze)

Ame-gusuri, meaning amber glaze, is an iron based glaze used on Aka-raku tea bowls. The 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu, first began using the technique, however, it was completed by the 4th generation, Raku Ichinyu.

When Ohi Chozaemon, one of Ichinyu’s students, became the founder of “Ohi ware” in the Kanazawa area, Ichinyu passed the technique down to Ohi Chozaemon.

After that, Ichinyu never used the amber glaze for making tea bowls as a consideration for Chozaemon. It became the Raku family’s custom, so the Raku family never used amber glaze on its tea bowls.

Suna-gusuri (sand glaze)

This glaze is made by adding fine grains of sand, such as silica, to red glaze. After firing, semi-molten sand appears and makes a rough textured surface similar to sandpaper. The 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu, first began using the technique, and the 14th generation, Raku Kakunyu, also like using this technique.

Gogaku (five hills)

Gogaku has a curved, wavy rim that resembles five hills. These “hills” prevent a tea scoop or a tea whisk from falling out when put on the rim. They also avoid making the design far too simple, giving it some complexity.The 7th generation Raku family descendant, Raku Chonyu, first began using the technique. The 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu, already made bowls with a wavy rim, however, they were more flat. Raku Chonyu perfected the technique and made bowls like this frequently.

Hamaguriba (the edge of a clamshell)

The rim tends to curve inward like the edge of clamshell. The 3rd generation descendant, Raku Donyu, first began using the technique.

Su-in (plural stamps)

The 7th generation, Raku Chonyu, began putting his stamps on his works as design.

Mashiko ware

It is generally agreed upon that Mashiko ware originated towards the end of the Edo period, in the year 1853 (Kaei 6). It was then that Keisaburo Otsuka, having learned the art of pottery in the city of Kasama, Ibaraki, traveled from what is now the town of Motegi, Tochigi to the town of Mashiko, where he discovered potter's clay and first lit his kiln.

The pottery industry continued to develop through the Meiji period, taking advantage of the bounties of the land to achieve Kanto-wide distribution of its wares. Around the same time, teapots decorated with simple landscape paintings were first created, and would go on to be produced in great numbers. Those teapots would later receive high praise from Hamada Shoji. However, towards the end of the Meiji period, as Tokyo (a major consumer of wares) modernized, the lifestyles of its residents began to change. This, combined with the rise of high-quality Kyo ware and the proliferation of rival Kasama ware, had a significant impact on Mashiko ware. This marked the beginning of a dark age for Mashiko.

After the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 (Taisho 12) struck Tokyo, Mashiko, which had been on the decline, received a new lease on life, thanks to the favorable economic conditions brought about by the earthquake. In the following year, Hamada Shoji, a master of the folk-art movement, established a pottery studio in Mashiko.

Awareness of Mashiko ware spread in concert with Hamada Shoji's fame. Finally, in 1955 (Showa 30), Hamada accepted a designation as a Living National Treasure for his exploits in the realm of folk pottery. Mashiko ware became known worldwide, and so the town of Mashiko came to achieve its current status and popularity among the general public.

Mino ware

Mino ware was very artistically influenced by Raku ware, however the potters aspired to depart from its influence: they made pottery freely while Raku ware was made by requests from Sen no Rikyu. Mino ware elevated artistic level of Japanese pottery. Mino ware includes Ki-seto, Seto-kuro, Shino and Oribe ware which are famous for their use in the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Shino ware is known for its almost pure white glaze, while Oribe ware is known for its green copper glaze, matte black glaze and bold painted designs. Ki-Seto ware is known for its green glaze, named Tanpan, and its matte yellow glaze. Seto-kuro is known for its pure matte black glaze, named Hikidashi-kuro.

Oribe ware

Oribe ware is a type of Japanese pottery most identifiable for its use of green copper glaze, mat black and bold painted designs. It was the first use of colored stoneware glaze by Japanese potters. It takes its name from tea master Furuta Oribe (1544-1615).Oribe ware has quite strange shapes. It was an innovative style at the time. It is said that the strange styles were made under Oribe's direction. He was pupil of Sen no Rikyu, Japans's most famous Tea Ceremony artist. In the Momoyama period, Rikyu was serving under ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi, while Oribe was serving under rival Tokugawa Ieyasu. In the battle of Osaka Natsu no Jin (1615), Tokugawa's troops defeated Toyotomi's. Thus Tokugawa became the ruler of Japan. Unfortunately he ordered Oribe to commit ritual suicide (seppuku) as a suspected spy of Toyotomi.In the present day, Oribe ware is very popular with Japanese antique collectors for its historical atmosphere and strange shapes.

Kizeto

Kizeto emerged from the tawny brown Koseto (old seto) style of the Muromachi period, and unlike Shino lacquerware that had its beginnings in the Momoyama period, the Kizeto of the Momoyama period was especially beautiful with a captivating charm; since antiquity masters of the tea ceremony valued both "Aburagete" and "Ayamete" for their high quality, matte appearance, and grainy texture.

Although most were originally made for Mukozuke (one of the side dishes) and treated as tea bowls, there do exist some that were made to be tea bowls.

For Kizeto, when the clay is half-dried lines are drawn on with a twig or piece of bamboo, and the side is struck with copper chalcanthite. Copper chalcanthite turns green when baked via oxidation, a special trait of Kizeto that pairs well with scorch marks.

Setoguro

Also known as "Tenshokuro" due to its origins in the Tensho era. It is also called "Hikidashikuro" from the act of removing it from the kiln when it is glowing red.

Many are cylindrical in shape and are made at an incredibly low elevation.

The lacquer is done in the style of Oni-ita where ash is mixed in, and when removed from the 1100℃ kiln with a pair of metal tongs, rapid cooling causes the color to turn black (rapid cooling can also be achieved with water). The tongs leave a mark which is one of the traits of this style.

A similar kind of black tea bowl is found in Kyoto, known as "Kuroraku". It is similarly removed from the kiln during firing and subject to rapid cooling, and while it shares the same method of applying a jet black metal lacquer, it differs from the Mino style's high heat and potter's wheel casting, whereas Kuroraku is completely handmade with low heat.

Shino ware

Shino ware is one technique of ceramic art that flourished during the tea ceremony craze of the Momoyama period; it was the first white pottery to be created in Japan. Due to its white color, images can be drawn on the sides, also making it the first pottery in Japan to feature brushed-on paintings. Although it declined in popularity after the Edo period, at 1930 the early of the Showa era the discovery of old Shino kilns by Arakawa Toyozo ( 1894 – 1985 ) along with subsequent research led to a second revival for this art form.

In the traditional method of production, a mould is cast using eggshell-colored "Mogusa" dirt, a specialty of the Mino region with a light stickiness like brown sugar, after which a thick feldspar glaze is applied and the pottery is fired.

Shino ware has its origins in the traditional incense smelling ceremony of the Muromachi period where it belonged to the "Shino School", founded by Shino Soshin ( ? – 1480 ) who was ordered to produce pottery for the Mino region. Let's take a look at several representative techniques of this ceramic art.

Muji (Plain) Shino

Simple and unpatterned, with a white glaze.

E Shino

Images are drawn beneath the white glaze. Images are drawn on the first coat with a metal powder known as "onisaka", after which another layer of glaze is applied and the pottery is baked.

Nezumi Shino

Has a white pattern done in an inlay style. Baked after the base coat of onisaka is scraped off, which results in the remaining metal particles turning red and grey with the scraped off portions remaining white.

Aka Shino

Although fired using the same method as Nezumi Shino, those that come out red are called this.

Beni Shino

Metal images are drawn like in red raku pottery, and the pottery is fired after a coat of Shino glaze is applied.

Mumyoi ware

Mumyoi is a type of red soil which contains a rich amount of iron oxide which is produced from around the Gold Mine, and the Mumyoi pottery uses it as its pottery clay, which is then baked at high temperatures.

The character of the clay is such that it requires special work such as polishing while raw and then polishing it with sand after baking it.

In addition, the pottery clay goes through "elutriation" - a way to get rid of sand and impurities in the process of balancing the clay particles - using a 200-mesh sieve which makes the baked pottery clay shrink by around 30% due to the loss of these particles.

Therefore the product is extremely hard and when hit it makes a clear metallic sound and the more use it gets the more it shines.

The Mumyoi Ware products are gaining attention as a means of improving the taste of tea, alcohol, beer and coffee.

In China, Mumyoi had been used as a type of herbal medicine to cure hemostasis since ancient times, but as they did not know the source of the effect they seemingly named it Mumyoi (no name). In Japan this was gathered only around the Sado Gold Mine. It was a byproduct of mining operations during the 1640s - the height of the gold rush on Sado Island after the discovery of the Aikawa mines.

The history of Mumyoi ware began with Ito Jinpei creating Raku Ware using the Mumyoi produced from the Sado Mines in the 2nd year of Bunsei (1819).

Afterward, Miura Jozan (1836-1903) realized that Mumyoi produced from the Sado Mines has a very similar nature to Yixing clay. He doubled his efforts to change the usual Mumyoi ware, which was quite fragile, into strong pottery similar to the pottery created from the Yixing kiln in China, and he completed a piece of strong, high-temperature Mumyoi pottery. Tea tools in Mumyoi ware became popular among people who like green tea because they made tea delicious like Chinese Yixing ware.

According to a record, the famous shogunate retainer, Katsu Kaishu bought tea tools from Miura Jozan.

In 2003 Mumyoi Ware was registered as a National Important Intangible Cultural Property.

The Agency for Cultural Affairs is attempting to register Sado Aikawa gold mines in the World Heritage List now. Unfortunately, because of this, it became very difficult for potters to obtain Mumyoi from around Sado Aikawa gold mines because collecting the mine soil from the area was banned.

Ofukei ware

The name "Ofukei" comes from the official kiln of the Owari branch of the Tokugawa Clan, sited in the Ofukeimaru outer cloister of Nagoya Castle. Originally, around 1610, the first clan head of the Owari Clan, Tokugawa Yoshinao (ninth son of Ieyasu), gathered and employed famous craftsmen from the nearby Seto area in order to protect the industry. At the time, the work centered around the three craftsmen Jinbee, Tozaburo, and Tahee, but their family lines continued the industry. Although there was a temporary interruption, the tenth clan head Tokugawa Naritomo (1793-1850) allowed Kato Tozaemon to rebuild the kiln, and production continued until the abolition of the clan system. The clay used was Ubakai clay of the same area and, at first, they used reddish brown glaze; however, from the middle period, verdigris porcelain glaze emulating Joseon dynasty pottery appeared and became established as Ofukei-style glaze. Following the reestablishment of the kiln, other forms of pottery imported from various regions such as Annam were manufactured.

Ohi ware

In Genbun 6 (1666) Tsunanori, fifth of the Maeda line and daimyo of the Kaga Domain, wanted to cultivated tea culture and invited the 4th head of the Uransenke school of tea ceremony, Senso (Soshitsu Sen), to be the tea ceremony magistrate. At that time Senso was accompanied by a potter and tea bowl master, Chozaemon, who was the best student of the 4th head of the Raku line, Ichinyu.

Chozaemon was searching for the best potter's clay and upon discovering it in Ohi village in Ishikawa prefecture, he continued living and making pottery there in Kaga. He then took the surname Ohi from the village and it continues to be used to this day.

Ohi- ware is "Wakigama" (which is a general term for kilns used to make Raku ware that are outside of the Raku line) of the Kyoto Raku line. Raku ware has spread throughout Japan since the Meiji period, but in terms of makers who have directly inherited the Raku line techniques, Ohi ware is said to be the only current Wakigama with such lineage.

Fine quality earth is coated with a red-yellow glaze, commonly known as Ohi Amber glaze, and fired at a low heat of 750-850 degrees. Ohi ware is defined by the brilliant reddish-brown luster of the bowls' surface created by using the Amber glaze.

Sanda ware

Sanda celadon was an attempt by Japan to recreate the Chinese Longquan celadon. During the mid-18th century, in Sanda city of the present-day Hyogo prefecture, the potter Uchida Chube sought financial investment from the wealthy merchant Kanda Sobe. Kanda responded to Uchida's passion and with his support, Uchida began his work. Later, in Kyoto, he met the master craftsman Kinkodo Kamesuke, and they focused on the mass production of excellent molded ceramics. They were successful in making celadon that rivaled even the Longquan celadon, and the fame of the "Sanda celadon" grew rapidly.

The Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-1830) were a golden age for sanda celadon. During that time, it is said that there were four kilns with a total of three hundred potters employed for the production of a wide range of crafts including incense burners, tea utensils, vases, human figures, ornaments, plates, and more.

Sanda celadon, which has been praised as "Japan's best celadon," met its demise in 1944.

Satsuma ware

The history of Satsuma Ware during the Bunroku and Keichou Eras (1529-1598) began during the famous "Imjin War (1592-1597)" called as Ceramic War, when Simazu Yoshihiro, the seventeenth head of the Satsuma Han, kidnapped more than 80 Korean potters and brought them back to Japan. Potters, including Boku Heii and Kin Kai, who arrived in the towns, Kushikino and Ichiki, started kilns within the Han domain. Each kiln produced a different style of pottery dictated by the environmental conditions of the location and the style of the potters, making a large variety available. Later, there were 5 varieties of kilns: Naeshirogawa, Tateno, Ryumonji, Nishimochida, and Porcelain. Collectively, they are known as Satsuma ware. Three types: Naeshirogawa, Ryumonji, and Tateno, still remain today. Satsuma ware is separated into two categories with different aspects, Shiro Satsuma and Kuro Satsuma.

Shiro Mon (white satsuma)

Shiro Satsuma, called Shiro Mon, is formed from white potter's clay with a transparent glaze, and features tiny cracks on the surface. Until white potter's clay was found in the area currently known as Hioki, it was fabricated using clay that was brought by potters from the Korean Peninsula. Since the materials and technology, save the fire, was of Korean origin, it was called hibakaride. The discovery of white clay was an extremely important event for Shiro Satsuma, which exclusively relied on precious Korean white clay.

Shiro Satsuma was fired in the Tateno and Naeshirogawa kilns, and was for use only within the Han and Shimazu household and not for the eyes of the general public. As part of cultural promotion measures, the Han dispatched craftsmen to Kyoto to study techniques, such as colored enamels and gold patterns and was the only Japanese display of art at the International Expo in Paris in 1867. White Satsuma captivated many Europeans and was widely known as SATSUMA .

Kuro Mon (black satsuma)

Kuro Satsuma, called Kuro Mon, in contrast to Shiro Mon, is loved as pottery for the common people. Using local soil, Kagoshima, home to Sakurashima with a large deposit of volcanic ash rich in iron, is able to produce a solid black pottery. Firing the iron-rich soil at high temperatures, creates a pottery featuring a rustic and rugged finish. This is the reason that it is perfect for daily use. Using three kinds of glaze: black, brown and buckwheat, a wide variety of pottery from tea bowls to common dishes have been made.

Seto ware

Although legend has it that ceramics in the Seto ware began when its forefather, Kato Shiroemon Kagemasa, built a kiln there in 1242 after having studied the methods from the Song dynasty in China, the origins of pottery-making in the area are much more ancient, dating back to the Tumulus period.

During the Kamakura period the Seto ware was the only one in Japan which produced glazed pottery. The flourishing of trade between Japan and the Song from the Heian to the Kamakura period led to a large volume of ceramics being brought in from the continent; the extant domestic ash glaze could no longer compete, which led to various changes in the Seto ware as well.

By the Muromacho period the tea ceremony had become popular, and once the Seto potters made tea things preferentially. The role of Seto region became a producer of practical tableware.

During the Warring States period many potters fled Seto for Mino in order to escape the war, as the term "Seto-yama-risan (Flight from Seto mountain)" suggests, where they received protection under the policies of Oda Nobunaga. Bowls and decorative plates with the distinctive style of Seto ware, Oribe, Shino and Ki-seto have been discovered in the remains of Mino's kilns from this period.

Upon entering the Edo period, the potters who had left Seto as part of the "Seto-yama-risan" returned to Seto region once again. The Owari branch of the Tokugawa family summoned the potters back to Seto as part of the so-called "Kamadoya-yobimodoshi (Summons to the kilns)", and the Seto area flourished once more.

However, the Seto area entered a difficult period due to their delay, as Kyushu's Arita ware expanded their sales routes from Imari port to Europe and beyond thanks to the temporary halt in exports from China, the biggest producer of ceramics.

In the late Edo period (1807), Kato Tamikichi, who had studied ceramics in Kyushu's Arita area and elsewhere, returned to Seto and regularized ceramic production there, leading to a dramatic change in Seto's pottery scene.

From that point onward, Seto's ceramics adapted well to the styles of the period and expanded production, even frequently exporting overseas during the Meiji period.

Japan the term "Seto-mono (Seto item)" is synonymous with ceramics at the present time.

Shigaraki waer

Shigaraki ware is one of ‘The Six Old Kilns’ in Japan made in Shigaraki, Koga shi, Shiga Prefecture. Shigaraki is the area once flourished as a center of Japanese culture in the middle of Kamakura period, with a strong influence of Korean culture. Later in Muromachi period when the tea ceremony was established, the Japanese sense of beauty "Wabi-sabi" and the simplicity of yakishime (unglazed pottery) became integrated and Juko Murata (1423-1502), the founder of tea ceremony, introduced Shigaraki ware into tea utensils. The charm of Shigaraki ware lies in its unique glazing caused by yohen (color variation during firing). Natural glaze and unexpected variation caused by yakishime give pottery various shades and patterns called Keshiki (scenery), which has a wide variety such as nawame (cable), hiiro (scarlet), koge (burnt) or hai-kaburi (ash-covered); it could be said as a highlight of appreciating Shigaraki ware.

Shitoro ware

Shitoro ware refers to pottery produced in Kanaya, Shimada City, Shizuoka Prefecture. It can be traced back to the Muromachi period, beginning with the pottery baked in Mino, and has been long-known as a region ripe with high quality potter's clay. In year 16 of the Tenshou era, a license granted by Tokugawa Ieyasu promoted the region's pottery as a specialty good, and production flourished.

Above all else, the reason for Shitoro ware rising to acclaim was due to the attention received from Kobori Enshu and other practitioners of tea ceremony, as well as its selection as one of the Enshu Nanagama. Even now, they primarily make reddish tea kettles with yellow and black glaze, a much sought-after style. The often-appreciated vessels are exceedingly sturdy and moisture-resistant. The most famous examples are engraved with "Sobokai" and "Uba-futokoro".

Soma ware

The founder Tashiro Gengoemon (later Seijiemon) trained under Ninsei and, following his return to his hometown, the Nakamura Clan's kiln manufactured pottery from the Bakumatsu period through the Meiji era and continues to the present day under the 15th generation head of the kiln, Tashiro Hideto.

During the time of the Seijiemon the second, Kano Naonobu received the invitation of the Nakamura Clan in service to Soma and at that time drew an emblem of a running horse. Many splendid works, mainly tea vessels, inscribed or inlaid with the horse mark were made from that time on and still remain today.

Takatori ware

A historic prefectural workshop with a 400 year history of continued production in Fukuoka City's Sawara District, as well as Nogata City in Fukuoka Prefecture.

Takatori ware was originally fired at the base of Mount Takatori in Fukuoka Prefecture's Nogata City, and because of the Imjin War, Kuroda Nagamasa brought back a Korean potter named Hassan (Japanese name Hachizou Shigesada) who began baking Takatori ware. The workshop is said to have opened in 1600. The kilns at the workshop - Eimanji, Takuma, Uchigaso, and Yamada - are known as "Old Takatori". It prospered as the official kiln for the Kuroda province during the Edo period, and by the Genna era, they summoned a potter from Karatsu and improved their technique. With the arrival of the Kanei era, the second daimyo Kuroda Takayuki increased relations with Kobori Enshu, producing many of Enshu's favorite pieces. By that connection, it was included as one of the Enshu Nanagama, and became well-known as a production center for tea bowls. At present, their focus is on some of Enshu's favorite refined tea bowls fired in the Shirahatasan kiln, known as "Enshu Takatori".

Tamba ware

The Tamba style of pottery, a specialty of Hyogo prefecture, is a traditional industry of the town of Konda (now the city of Sasayama). It stands alongside the Seto, Tokoname (Aichi prefecture), Shigaraki (Shiga prefecture), Bizen (Okayama prefecture), and Echizen (Fukui prefecture) styles as one of the "Rokkoyo", or six old pottery styles of Japan, with a long and storied history that has continued to the present day.

Until recently, owing to a lack of records from the middle Kamakura period, it was thought that the style originated during the Kamakura period. However, in 1977 (Showa 52), the Hyogo Board of Education conducted an archaeological investigation of a kiln midden, concomitant to the renovation of a prefectural road. The excavation revealed old-Tamba vases with illustrations and engravings, dating from the late Heian period to the early Kamakura period, along with other vases and pots. This discovery made it clear that this was the birthplace of Tamba-yaki, and that the style originated in the late Heian period.

Tamba ware undergoes beautiful changes in color as it is baked. The clay is fired for roughly sixty minutes in an ascending kiln at a peak temperature of 1300 degrees Celsius. The ash produced by the burning fuel (pine logs) then falls into the kiln and fuses with the glaze, producing fascinating colors and patterns called "hai-kaburi" that are unique to each vessel thus created. Thanks to this most-distinctive feature of Tamba ware, pottery in the style is not just prized for its practical merits, but also widely appreciated by connoisseurs of earthenware for its aesthetic value.

Tokoname ware

The Tokoname kiln has the longest history and had the largest production area among Japan's six old kilns (Tokoname, Shigaraki, Bizen, Tamba, Echizen, Seto). Its beginning dates back to the late Heian period (approx. 1100 AD), and an estimated 3000 Anagama kilns (tunnel kilns) were built in the hilly areas of the the Chita Peninsula in the Aichi Prefecture, centered at Tokoname City. Tsubo (jars), Kame (wide-mouthed bowls), and Yamajawan (mountain tea bowls) were made using these kilns. Tokoname wares made during the Heian period up to the early Edo period are referred to as "Old Tokoname."

During the latter part of the Edo period up to the Meiji period, the adoption of China's Shudei (unglazed reddish brown pottery) and European techniques led to a rapid increase in the production of Tokoname wares. "Tokoname Ware" refers to earthenwares made since ancient times in the Aichi Prefecture, centered at Tokoname. It is still a firm favorite.

In the past, there used to be huge lakes in Aichi, Mie and Gifu prefectures including Tokoname. This lake, called Lake Tokai, was a larger lake than the current Lake Biwa. The production areas of Tokoname ware, Shigaraki ware, and Iga ware were once in this lake.

Originally, Tokoname-ware was famous for its red stoneware, which had excellent performance in the taste of the tea. Tokoname's vermilion stoneware spread among people who like tea because the taste of tea becomes mild with it.

Tokoname's vermilion stoneware was started by a person named Sugie Jumon (1827-1897). At first, the stoneware was developed from the desire to make a good teapot like Yixing China on Japanese vermilion mud. For this reason, many of the teapots made by Sugiei were made by imitating Yixing teapots, and of course, Sugie himself understood the goodness of Yixing natural vermilion mud. In Tokoname at that time, the teapots were baked using Tokomame’s natural vermilion mud, and its quality was very high.

Unfortunately, now cheap teapots made from a mixture of red‐ocher rouge and vermilion mud have become mainstream. It looks bright and beautiful in vermilion, but if you want a teapot that improves the taste of tea, like a teapot made of natural vermilion mud, you have to buy expensive items or vintage items.

(Note) "vermillion mud" refers to the soil that changes to vermillion from ocher when oxidized and fired with the singular exception of Mumyoi. The soil of Mumyoi ware is vermilion before oxidized and fired.

Tsuboya ware

Okinawan pottery is the foundation for Tsuboya ware, a fusion of pottery techniques obtained through commerce with the south and Korean potters' methods directly transmitted from Satsuma. In 1682, the Ryukyu royal government integrated the Chibana Kiln of Misato Village (now Okinawa City), the Takaraguchi Kiln of Shuri, the Wakuta Kiln of Naha, and other regional kilns into the south of Makishi Village (now Tsuboya-cho in Naha City) in order to make utensils for the local islanders. This was the start of Tsuboya ware and it continues to the present day.

Tsuboya ware is divided into two basic subtypes, ara ware (Nanban ware) and jo ware. Most ara ware, which is unglazed yakishime pottery, consists of miso pots, sake jugs, water vessels, and similar large containers. Jo ware is red clay painted white and glazed, and mainly consists of goods used daily, such as bowls, plates, and flower vases, as well as tea sets, sake vessels, and decorative articles.

Zeze ware

Zeze ware is the term for the pottery of Zeze in Otsu City, Shiga Prefecture. Famous for its tea bowls, it was selected one of the Enshu Nanagama. Praised by Enshuu as an example of "Kirei-sabi" for its characteristic iron glaze with tinges of black, as well as its simplicity and delicate design.

Jakatsu-gusuri (snake's scale glaze)It is usually a line of white glaze running down the edge of the black glaze. This glaze usually appears filamentous while the line is made to look fuzzy like a dispersion pattern, sometimes resembling a wave in the sea, however, this does vary between generations. It was invented by the 3rd generation Raku family descendant, Raku Donyu.