Vintage mashiko tea cup by Hamada Shoji #2786

- SKU:

- 2786

- Shipping:

- Free Shipping

- rim size: approx. 8.7cm (3 27/64in)

- tall: approx. 8.6cm (3 25/64in)

- weight: 231g (w/ box 450g)

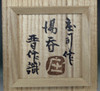

- the writing on the lid means "Yunomi (tea cup) made by Shoji authenticated by Shinsaku"

Hamada Shoji (1894-1978)

Hamada Shoji was a renowned craftsman and representative figure in modern Japanese pottery. Born in Tokyo in 1894, he resolved to become a potter while still a student at Furitsuicchu (the Tokyo First Prefectural Jr. High School, Hibiya high school at present). After studying ceramics at the Tokyo Higher Technical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), Hamada joined the Kyoto Municipal Ceramic Laboratory, where he would meet his lifelong friend, Kawai Kanjiro. As Hamada later summarized the narrative arc of his career, “I found the path in Kyoto, began my journey in England, studied in Okinawa, and developed in Mashiko.” In 1920, he accompanied Bernard Leach to England where he began his practice as a potter. When the time came to return home to Japan, he sought a quiet life in the countryside, and situated himself in the town of Mashiko in 1924. During this period, he also made an extended sojourn in Okinawa, which became the inspiration for a large number of works. In 1930, he relocated the building which would later become the main residence of his compound (later donated to the Ceramic Art Messe Mashiko), and in the years up until 1942, transplanted many traditional old houses onto the premises to create a workshop and residence. It was from this base that he founded the Mingei folk-art movement along with cohorts Yanagi Soetsu and Kawai Kanjiro, which was to have a significant impact on the Japanese craft world. In 1955, Hamada was recognized along with Tomimoto Kenkichi et. Al. as an inaugural recipient of the Japanese government’s “Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties” (Living National Treasure) designation, and in 1968, became the third potter to be awarded the prestigious Order of Culture.

The Mingei Movement

The Mingei (folk-art) movement was initiated by Yanagi Soetsu, Kawai Kanjiro, and Hamada Shoji in 1926 (Taisho 15) as an approbation of functional craftwork used by the masses in the course of daily life. At the time, the craft world was dominated by decorative pieces prized for their aesthetic value. In response, Yanagi and cohorts promoted the quotidian lifestyle implements handmade by anonymous craftsmen as mingei (“craft of the common folk”), arguing that such works have a beauty that rivals fine art, for beauty can be found in the everyday. A further pillar of the movement introduced a “new way of looking at beauty” and “aesthetic values” via the notion that crafts born from the local practices and rooted in the rhythms of the rural regions of Japan embody a utilitarian, “healthy beauty.” Their ideology was, in many ways, related to the era, marked as it was by the advance of industrialization and tandem gradual influx of mass produced products into the sanctum of daily life. Troubled by the loss of “handicraft” across Japan, the Mingei movement warned against the easy progression of modernization/Westernization. In this way, the Mingei movement served as a vehicle for the artists to pursue the question of what constituted a good life, rather than simply a life rich in material wealth.

Hamada Shoji (1894-1978)

Hamada Shoji was a renowned craftsman and representative figure in modern Japanese pottery. Born in Tokyo in 1894, he resolved to become a potter while still a student at Furitsuicchu (the Tokyo First Prefectural Jr. High School, Hibiya high school at present). After studying ceramics at the Tokyo Higher Technical School (present-day Tokyo Institute of Technology), Hamada joined the Kyoto Municipal Ceramic Laboratory, where he would meet his lifelong friend, Kawai Kanjiro. As Hamada later summarized the narrative arc of his career, “I found the path in Kyoto, began my journey in England, studied in Okinawa, and developed in Mashiko.” In 1920, he accompanied Bernard Leach to England where he began his practice as a potter. When the time came to return home to Japan, he sought a quiet life in the countryside, and situated himself in the town of Mashiko in 1924. During this period, he also made an extended sojourn in Okinawa, which became the inspiration for a large number of works. In 1930, he relocated the building which would later become the main residence of his compound (later donated to the Ceramic Art Messe Mashiko), and in the years up until 1942, transplanted many traditional old houses onto the premises to create a workshop and residence. It was from this base that he founded the Mingei folk-art movement along with cohorts Yanagi Soetsu and Kawai Kanjiro, which was to have a significant impact on the Japanese craft world. In 1955, Hamada was recognized along with Tomimoto Kenkichi et. Al. as an inaugural recipient of the Japanese government’s “Preserver of Important Intangible Cultural Properties” (Living National Treasure) designation, and in 1968, became the third potter to be awarded the prestigious Order of Culture.

The Mingei Movement

The Mingei (folk-art) movement was initiated by Yanagi Soetsu, Kawai Kanjiro, and Hamada Shoji in 1926 (Taisho 15) as an approbation of functional craftwork used by the masses in the course of daily life. At the time, the craft world was dominated by decorative pieces prized for their aesthetic value. In response, Yanagi and cohorts promoted the quotidian lifestyle implements handmade by anonymous craftsmen as mingei (“craft of the common folk”), arguing that such works have a beauty that rivals fine art, for beauty can be found in the everyday. A further pillar of the movement introduced a “new way of looking at beauty” and “aesthetic values” via the notion that crafts born from the local practices and rooted in the rhythms of the rural regions of Japan embody a utilitarian, “healthy beauty.” Their ideology was, in many ways, related to the era, marked as it was by the advance of industrialization and tandem gradual influx of mass produced products into the sanctum of daily life. Troubled by the loss of “handicraft” across Japan, the Mingei movement warned against the easy progression of modernization/Westernization. In this way, the Mingei movement served as a vehicle for the artists to pursue the question of what constituted a good life, rather than simply a life rich in material wealth.